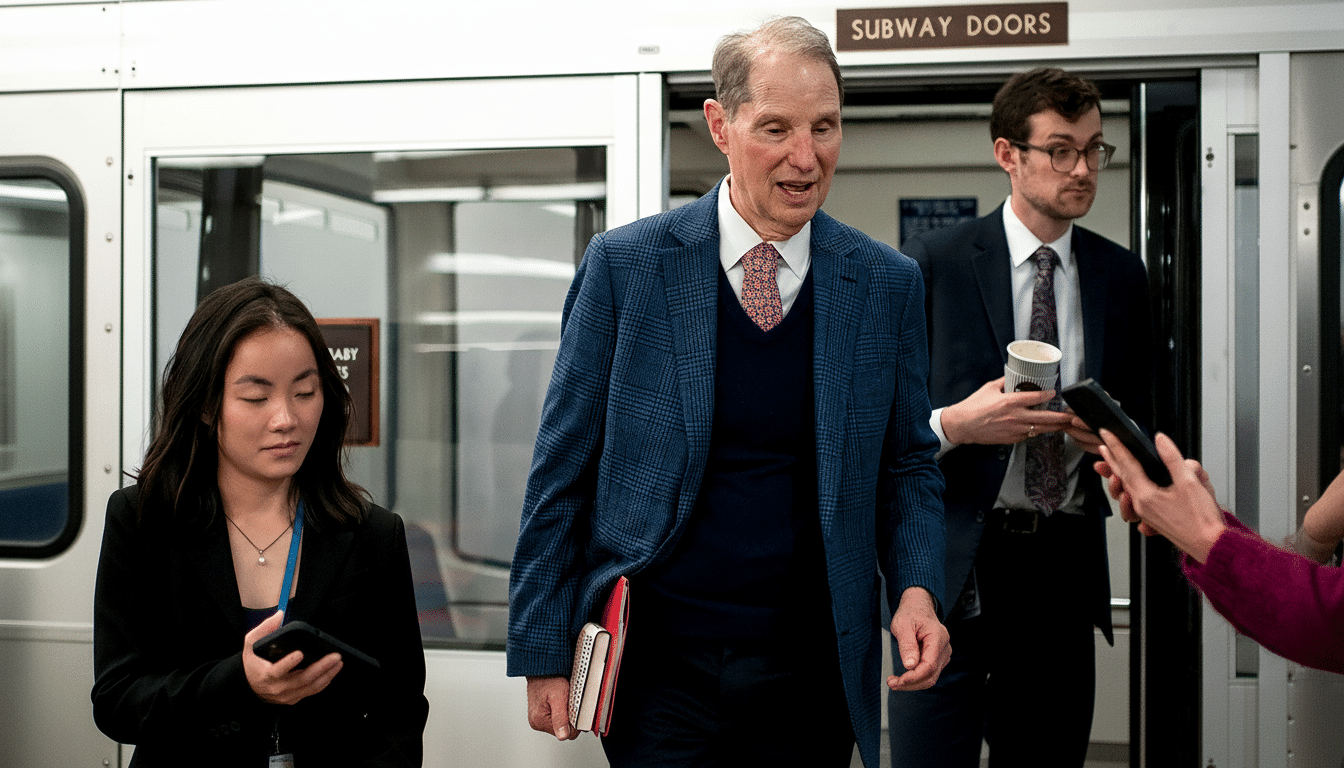

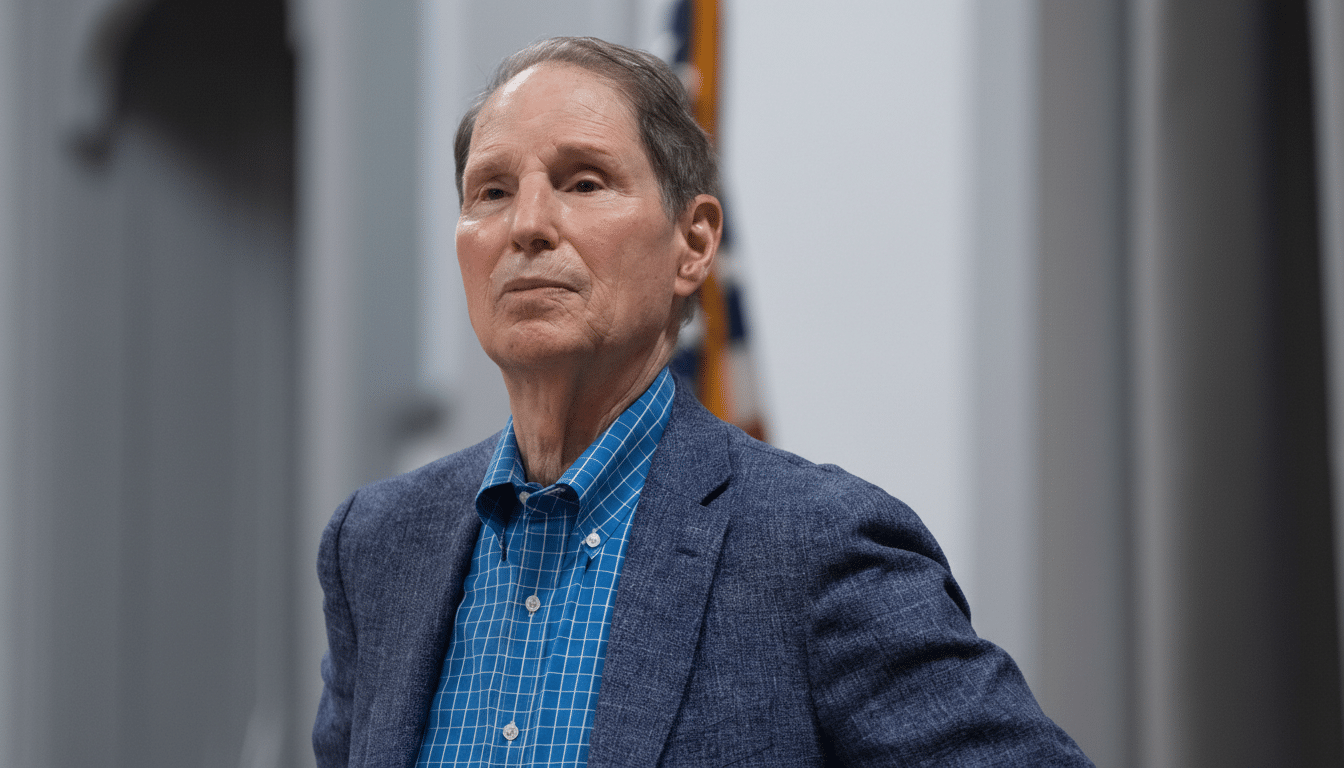

A senior Democratic senator long known for exposing hidden surveillance practices is warning of undisclosed Central Intelligence Agency activities, saying he has “deep concerns” after reviewing classified material. The rare signal from Sen. Ron Wyden, a veteran member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, immediately sharpened attention among civil liberties advocates and national security watchers who track his public hints as early warnings. The CIA, in a statement relayed by a national security reporter at the Wall Street Journal, dismissed the criticism as unsurprising and even framed it as a badge of honor.

A Familiar Warning Signal From Sen. Ron Wyden

Wyden’s carefully calibrated public notes have preceded major surveillance revelations before. Years ago, he cautioned that the government was relying on a secret interpretation of the Patriot Act. Months later, documents leaked by Edward Snowden showed the National Security Agency had used that secret reading to collect Americans’ phone records in bulk. Since then, Wyden has pressed agencies on everything from how authorities obtain the contents of communications to how federal investigators quietly compelled Apple and Google to share users’ push notification data, while barring the companies from telling the public.

Because members of the intelligence committees are often the only lawmakers cleared to see the most sensitive programs, Wyden is constrained from revealing specifics. His method has been to flag problems in general terms and push for declassification, a tactic that has frequently been vindicated by later disclosures or watchdog reports.

What May Be Driving The Senator’s New Concern

Although Wyden’s latest letter does not detail the conduct at issue, past oversight fights point to several flashpoints. One persistent worry is the government’s purchase of commercially available data—such as precise location information—from brokers. An Office of the Director of National Intelligence report concluded that such data can be “sensitive” and “personally revealing,” and that unchecked use risks eroding constitutional protections. The bipartisan Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, co-sponsored by Wyden, seeks to bar agencies from buying data that would otherwise require a warrant.

The CIA also operates primarily under Executive Order 12333, which governs intelligence collection outside the traditional court-supervised framework used by the FBI and NSA. That distinction matters: while surveillance under Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act draws regular reporting to Congress and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, EO 12333 activities rely more on internal rules and executive branch oversight. In a partially declassified review, the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board acknowledged the CIA’s acquisition of certain bulk data and urged stronger transparency and safeguards.

Separately, government transparency reports have shown dramatic swings in how often agencies query databases using terms associated with Americans. After public scrutiny and internal reforms, ODNI reported that FBI U.S. person queries dropped by more than 90% from earlier peaks. While those figures focus on the FBI’s use of 702 data, the underlying lesson—that guardrails and audits change behavior—has amplified calls to apply comparable rigor to EO 12333 and to any data broker purchases by intelligence agencies.

CIA Oversight And The Limits Of Secrecy Explained

Intelligence oversight is designed to be probing but largely classified. The Senate and House intelligence committees review programs, but nondisclosure rules limit what members can share publicly, even with colleagues not on the committees. That creates a recurring tension: when a senator signals a serious problem, the public must often wait for a declassification process, a watchdog report, or an inspector general finding to fill in the details.

The CIA, for its part, typically emphasizes that it is legally barred from spying on Americans and that it implements extensive compliance training, minimization procedures, and legal reviews. Yet watchdogs have argued that the line between foreign intelligence and incidental or purchased domestic data can blur in practice, especially as digital exhaust from apps, ad networks, and connected devices spills into the commercial marketplace and can be acquired in bulk.

Why Wyden’s Track Record Matters Now For Oversight

Wyden’s signals carry weight because several of his prior warnings foreshadowed landmark revelations. He questioned secret law under the Patriot Act before phone metadata collection became public, pressed for details on upstream internet collection that later drew court scrutiny, and exposed previously hidden demands for push notification data that Apple and Google have since acknowledged. Civil liberties groups like the ACLU and EFF closely parse his statements for this reason.

His newest alarm also lands as Congress continues to debate surveillance authorities and data broker practices. Lawmakers have floated measures that would tighten warrant requirements, mandate stronger auditing, and force declassification of key legal interpretations. The broader policy question—how to reconcile powerful foreign intelligence tools with constitutional limits at home—remains unsettled.

What To Watch Next In The Debate Over CIA Powers

Signals to watch include follow-up letters from the intelligence committees to the CIA and ODNI, requests for expedited declassification by the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, and new transparency reporting. Technology companies may also update their law enforcement disclosure reports if gag orders lift, as happened with push notification data. Finally, if inspectors general or the FISA Court publish opinions or audits touching CIA equities, they could shed light on the concerns Wyden is hinting at.

Until then, the senator’s brief message underscores a recurring dynamic in U.S. surveillance policy: the most consequential debates often begin with what isn’t yet public. When Wyden sounds an alarm, Washington tends to listen—and wait for the classified pieces to catch up with the public conversation.