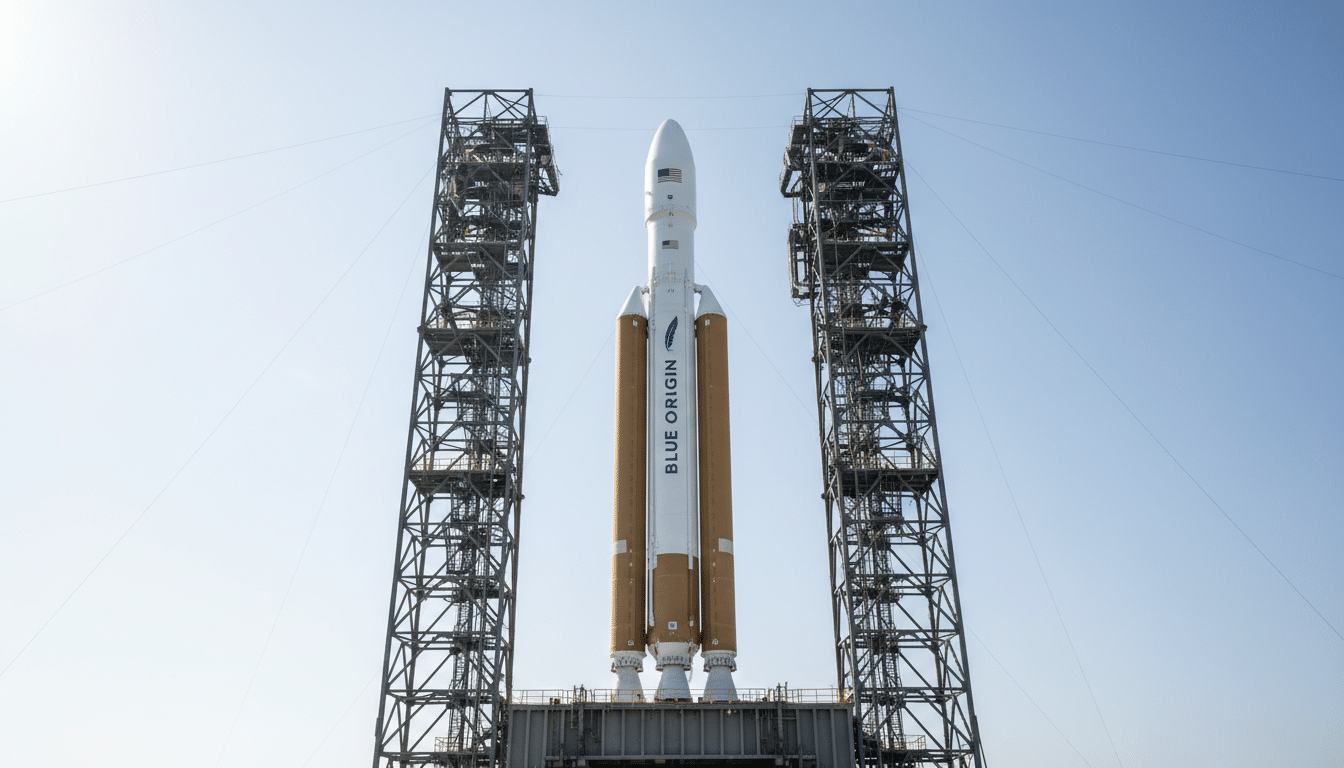

Blue Origin plans to fly its third New Glenn mission in the coming weeks, but the rocket won’t be headed for the moon. Instead, the heavy-lift launcher will deliver a commercial satellite for AST SpaceMobile to low-Earth orbit, marking the second time New Glenn carries a paying customer as the vehicle transitions from debut flights to a regular manifest.

A Strategic Pivot from Lunar Plans to Low Earth Orbit

The decision to fly a commercial payload now, rather than the company’s Blue Moon Mark 1 (MK1) robotic lander, underscores a pragmatic sequencing of risk and priorities. Blue Origin says the MK1 lander is headed to NASA’s Johnson Space Center for vacuum chamber testing, a crucial step that simulates the deep-space environment. That facility is home to the historic Chamber A, known for qualifying Apollo-era hardware and, more recently, the James Webb Space Telescope—an indication of the rigorous test regime the lander will face before launch day is set.

Shifting New Glenn’s third flight to a proven commercial satellite mission allows Blue Origin to keep cadence, gather more flight data, and refine operations before attempting a high-stakes lunar delivery. It also aligns with the company’s broader business model: demonstrate reliability to customers in orbit while maturing the technologies and processes required for planetary missions.

What AST SpaceMobile Gains from This New Glenn Flight

AST SpaceMobile aims to build a space-based cellular broadband network that connects directly to standard smartphones. The company’s previous on-orbit demonstration, BlueWalker 3, unfolded one of the largest commercial phased-array antennas ever flown—about 693 square feet—and validated key elements of direct-to-device service, including voice calls and data links. Partnerships with major carriers such as AT&T and Vodafone highlight the commercial stakes: a successful deployment on New Glenn strengthens AST’s pathway to scale.

For Blue Origin, flying another commercial payload extends a growing track record with satellite operators looking for heavy-lift capacity. New Glenn’s advertised lift capability—on the order of tens of metric tons to low-Earth orbit—positions it to serve larger single-satellite missions as well as clustered constellations, an increasingly common strategy in communications and Earth-observation markets.

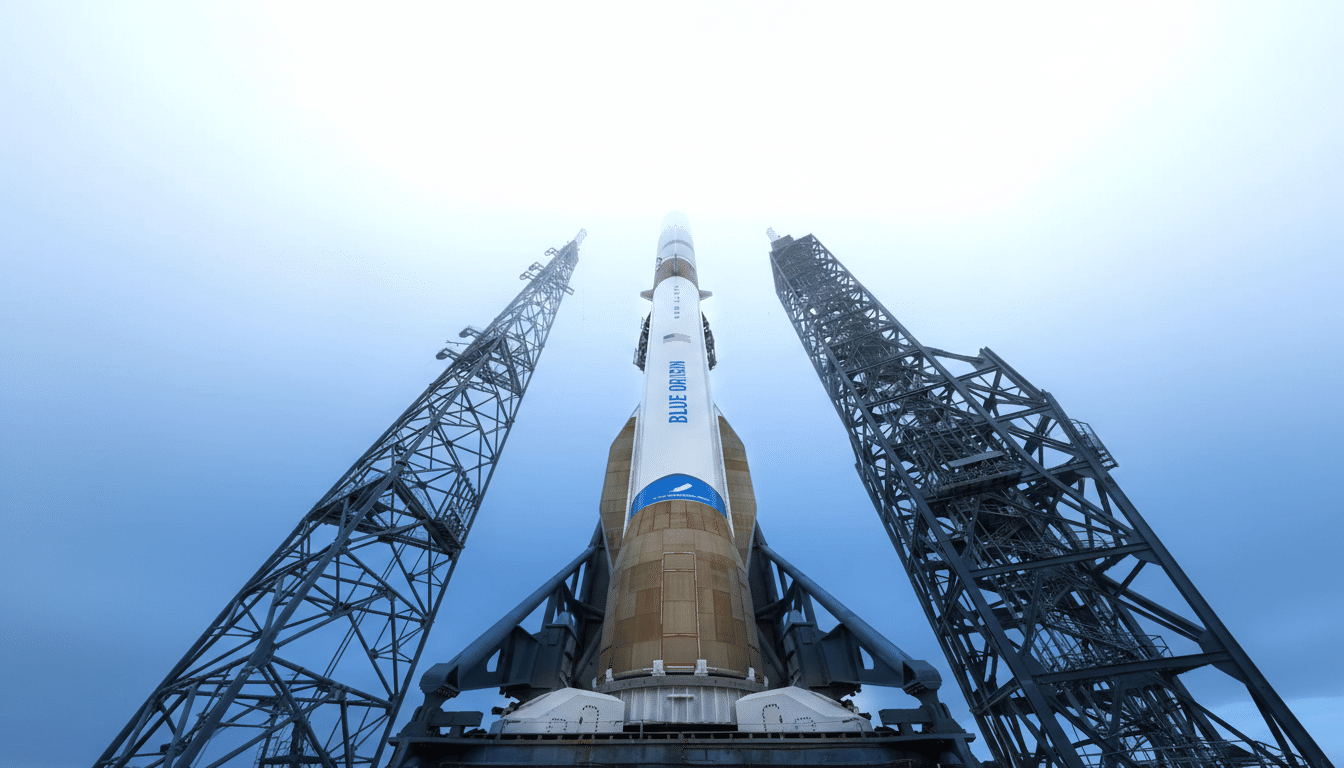

Reusability Takes Center Stage with a Reflown Booster

Blue Origin plans to reuse the booster from New Glenn’s second mission, which was recovered on an ocean-going drone ship. Reflight of that stage is more than symbolism—it’s a direct lever on cost and launch cadence. The booster’s seven BE-4 engines, burning liquid oxygen and liquefied natural gas, anchor the vehicle’s performance profile while laying groundwork for higher reuse counts over time.

SpaceX demonstrated how iterative reuse drives down unit costs and increases availability; Blue Origin is now applying similar economics at a heavier lift class. If the reflown New Glenn booster performs nominally, it will strengthen the company’s argument that rapid turnaround is achievable beyond the medium-lift regime.

Where New Glenn Fits In The Heavy-Lift Race

Standing roughly 98 meters tall, New Glenn is built to haul hefty payloads to orbit and beyond, bridging the gap between workhorse rockets and super-heavy vehicles. Blue Origin has signaled ambitions for an even larger variant rivaling the scale of SpaceX’s Starship and exceeding the height of Saturn V, suggesting the company is positioning for deep-space cargo and high-energy missions later this decade.

The orbital launcher builds on more than a decade of suborbital flight heritage from New Shepard, but the operational demands are different: orbital missions require higher velocities, more complex staging, and stringent recovery protocols. Demonstrating consistent performance on commercial flights will be essential as Blue Origin pursues government and defense contracts that demand tight timelines and exacting reliability.

The Bigger Blueprint Beyond One Launch for Blue Origin

While the upcoming mission is focused on LEO delivery, the company’s roadmap stretches across multiple fronts. The Blue Moon lander line targets cargo and, eventually, crewed lunar missions. Blue Ring, a multi-mission platform under development, is designed to host and deploy third-party payloads in diverse orbits. And a planned satellite internet constellation, TeraWave, would bring Blue Origin into direct competition with established broadband networks later this decade.

For now, all eyes are on prelaunch milestones:

- Payload integration

- Static-fire checkouts

- Range coordination

- Final regulatory clearances from the FAA

If the mission proceeds as planned, Blue Origin will notch another data-rich flight for New Glenn, advance AST SpaceMobile’s constellation goals, and keep momentum while its lunar hardware undergoes critical testing at NASA.

It’s not a moonshot—yet—but it’s a calculated step toward one, and a sign that New Glenn is beginning to find its operational rhythm.