Stanford academics have released an online tool that can drain much of the venom from political Twitter — and it doesn’t use a drop of curare. In fact, in a randomized experiment published in Science, the simple act of reordering posts from their X feeds to downplay “partisan animosity” reduced hostility toward members of the opposition party by more than two points on a standard 0–100 feeling thermometer after just 10 days.

What the Stanford Tool Really Does to Reduce Rancor on X

The tool doesn’t block or censor content. Instead, it silently depresses posts that exhibit clear signs of partisan rancor — think calls to imprison political opponents or violent cheering — while leaving the rest untouched. The result: you still encounter a variety of opinions, but the most inflammatory stuff doesn’t enjoy pride of place at the top of your feed.

Since it runs in the user’s browser, in principle there is no reliance on the X platform or any other network for assistance with the intervention. It’s a ranking tweak, not a censorship lever — more akin to sorting your inbox than deleting messages.

Inside the Experiment: How the Study Measured User Attitudes

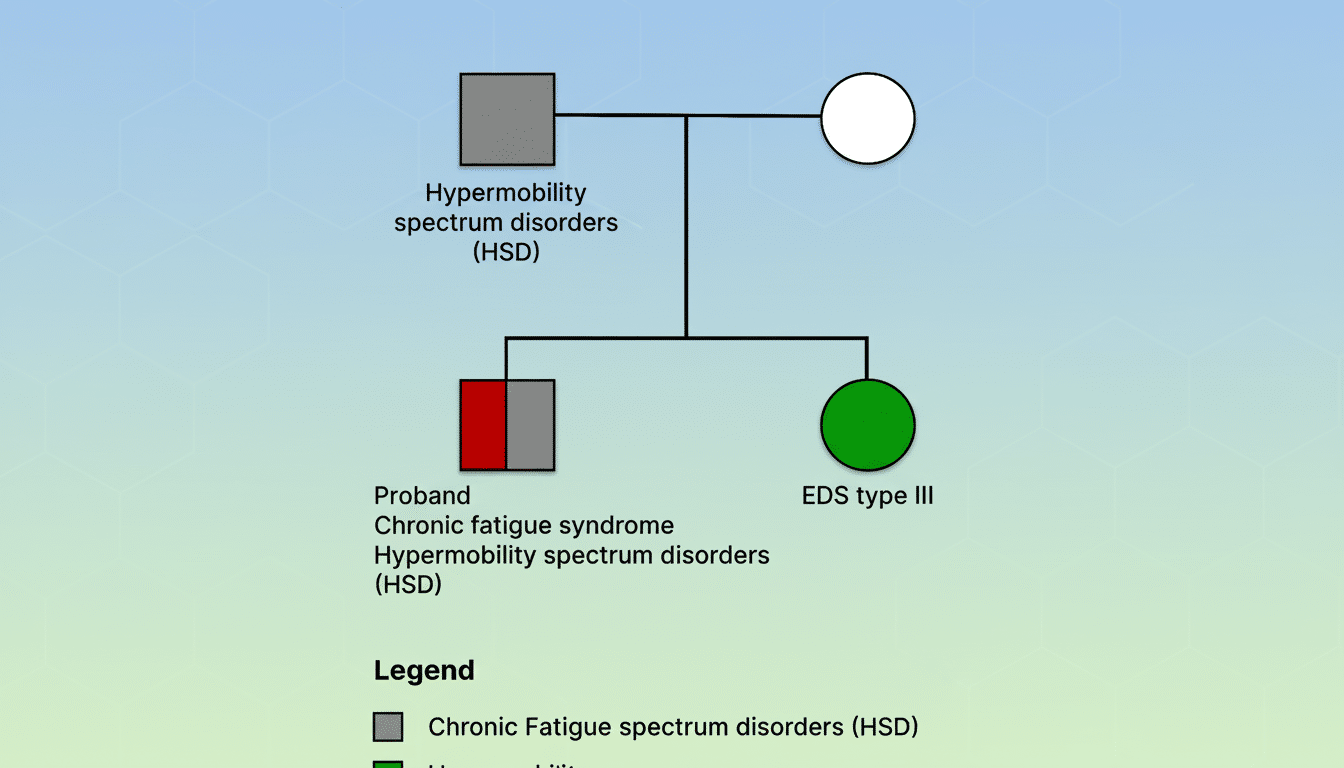

The team enlisted 1,256 current X users during the U.S. presidential election and requested that they use the tool for 10 straight days. Godsell is one of several researchers who measured attitudes using a standard political science instrument — the so-called “feeling thermometer” — on sentiment toward their own party as well as toward the opposition party.

By the end, out-party hatred fell by more than two points. The effect was consistent across party lines; both self-identified Democrats and Republicans exhibited similar shifts. And emotional reactions moved, too: anger dropped a notch, sadness went down a little, and positive emotions like excitement and calm stayed the same.

One big caveat: the study did not follow whether the benefits lasted beyond those 10 days. How long the gains lasted, and whether they were sustainable through light regular “maintenance” use, is an open question that the authors say should be addressed in future work.

Why Ordering Is Better Than Outrage in Engagement-Driven Feeds

Feeds engineered for engagement tend to favor content that elicits strong emotions, and outrage usually wins on that score. That dynamic has been well documented; for example, MIT research has demonstrated that false stories spreading on social media behave as a contagion, spreading more than true ones in part because they prompt reactions.

Stanford’s approach is intentionally minimal. It doesn’t judge policy positions or scour controversial viewpoints; it focuses on a narrow band of content where the message isn’t persuasion but antagonism. This small shift in exposure patterns — less politicking as blood sport at the top of the feed — was sufficient to change attitudes en masse.

The results also mirror more general survey work by groups like the Pew Research Center, which has said that lots of Americans feel social platforms make political conversation angrier and less civil. If rankings reward the sharpest elbows, softening that incentive structure a bit can alter what people feel as they advance down the screen.

What It Means for Platforms and Users Seeking Healthier Feeds

The findings suggest a pragmatic way forward for platforms grappling with polarization: algorithmic interventions that downrank hostility without having to remove speech. Companies might create optional controls — call them “de-prioritize antagonism” toggles — so that users can seek a healthier content mix without abandoning political discussion altogether.

To users, at least for now, the Stanford prototype suggests that client-side tools can take back some control of what comes into focus. It also recommends that detoxing a feed is not about living in a bubble; it’s about cutting the attention and validation subsidy for content that treats political enemies as villains rather than fellow citizens.

Limits of the Study and the Way Forward for Social Platforms

As hopeful as the results are, they’re small and time-bound. The two-point move on a scale of 0 to 100 is newsworthy at the population scale but won’t, by itself, cure polarization. The experiment was on X; replication across platforms, communities, and languages will be necessary.

There are some critical unknowns: Do the effects of grading practices accumulate, plateau, or attenuate over time? How do interventions overlap with viral events? Might a deprioritization of animosity limit the extent to which legitimate, albeit heated, activism becomes contagious? The authors acknowledge these trade-offs and propose transparent, auditable systems for independent researchers to assess what impact they may or may not have had in the wild.

Still, the conclusion is nicely concrete: changing what floats to the top of a feed — even just a little bit — changes how people feel about politics. That offers a blueprint for platforms and users to dial back the hostility without silencing debate, and to move one step closer toward a healthier digital public square.