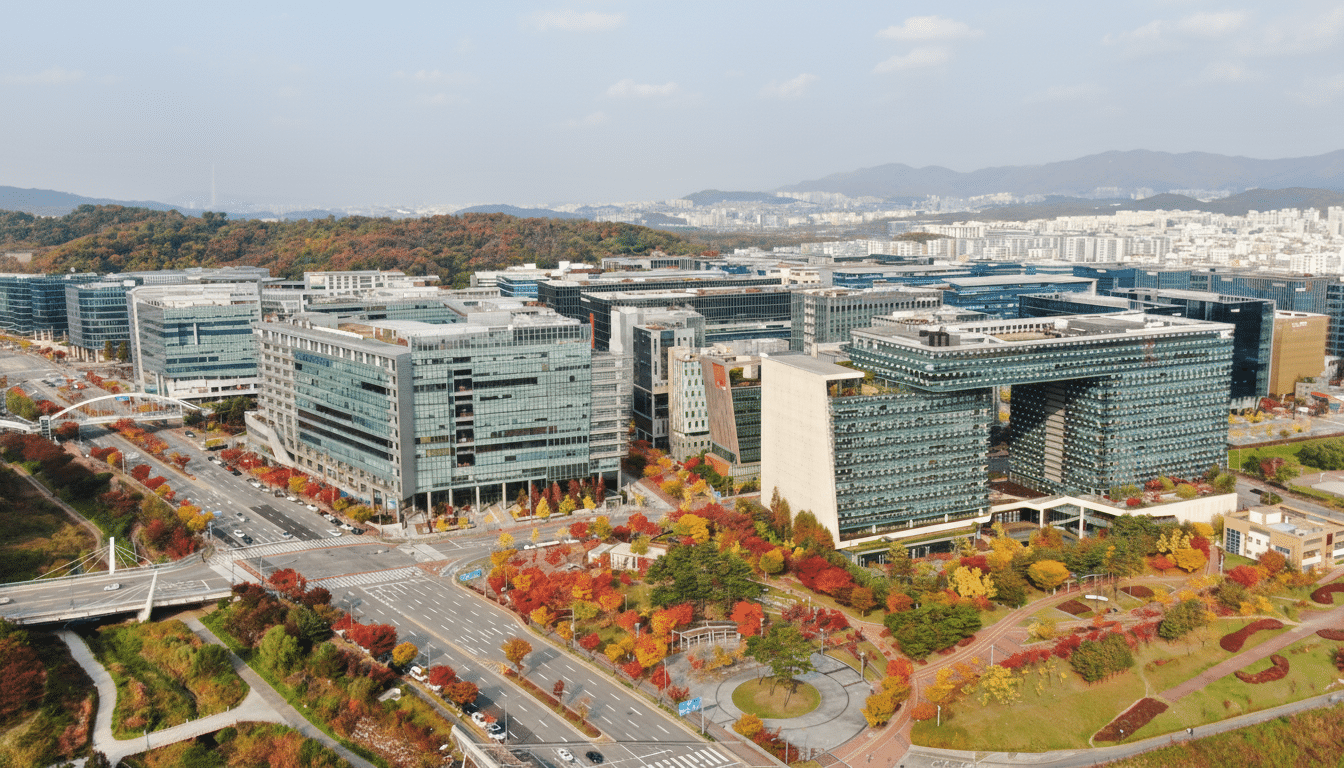

And 15 minutes south of Gangnam, Pangyo Techno Valley was constructed to serve as South Korea’s version of Silicon Valley — a dense grid of glass towers home to internet giants like Naver and Kakao, chip makers and hundreds of startups. The concentration is impressive. The global influence, less so. All that scale, however, has yet to translate into the kind of breakout companies and exits — or influxes of talent — that characterize a truly world-leading tech hub.

On paper, Pangyo seems to be a powerhouse. The district houses more than 1,800 businesses in some 660,000 square meters of space, according to the North Shore website, which says approximately 91.5% of them are small- and medium-sized companies. Naver, Kakao and Nexon are there alongside NCSoft and SK Hynix and HD Hyundai; they’re next to the likes of cybersecurity pioneer AhnLab as well as younger enterprises and research centers. But density hasn’t yet added up to the outsized global sway implied by the “Korean Silicon Valley” moniker.

Scale without breakout impact on global markets

From within Pangyo, Korea’s most valuable platforms and game studios have grown up, while deep tech efforts in semiconductors, autonomous driving (including Hyundai’s 42dot), and AI have proliferated.

Still, the activity remains largely domestically focused. Seoul is just outside the top 10 on Startup Genome’s recent ecosystem rankings, a very good position but not an elite one. The gap appears in late-stage capital, cross-border M&A and founder mobility.

Korea Venture Investment Corp. has spotted an ongoing late-stage funding hole, despite the fact that seed and Series A continue to hum. According to CB Insights and other trackers monitoring the venture capital market slowdown around the world, Korea wasn’t immune from those trends either, revealing a dependence on domestic IPOs versus international exits. There are notable outliers — Coupang’s New York listing and Delivery Hero’s purchase of Woowa Brothers, to name but two — but no drumbeat of global victories based in Pangyo.

The center of gravity continues to shift toward Seoul

For urbanites, location counts — however close the subway is. Venture firms, growth equity funds and corporate deal teams have all converged on Teheran-ro in Gangnam District for good reasons; hiring or securing funding from an investor can all be completed within a single block. Young engineers pursuing choice and energy are drawn to Seoul’s denser, more eclectic areas. For early-stage founders, being close to that is often more appealing than Pangyo’s attractions.

Policy geography amplifies the divide. Support programs for startups are often connected to city or provincial budgets, and Seoul’s initiatives — such as the Seoul Startup Hub and Seoul Fintech Lab in Yeouido — offer visible magnets for founders and foreign talent. To its credit, Pangyo does still play host to national programs, such as the K-Startup Grand Challenge at NIPA, but it’s generally the daily deal flow and investor serendipity that tend to work themselves out in the capital.

Culture, speed, and storytelling gaps hinder globalization

South Korea is a global leader in R&D intensity — OECD numbers consistently place the country at or near the top when looking at research and development as a share of GDP. It is that scientific strength that enables Pangyo’s engineering depth. What is harder to import is the culture of rapid experimentation, fluid job-hopping and comfort with failure that drives Silicon Valley. Investors often remark that Korean startups validate well and scale late, resulting in robust products but slow global sprints.

There’s also a storytelling gap. Founders here are typically scrappy on metrics and resource allocation but underprepared when it comes to writing the crisp, human narratives that convince both foreign customers and investors. KOTRA’s market-entry advice often highlights localization, the ability to sell in English and clearer value propositions. In industries such as AI, robotics and enterprise software, strong research can hit a wall without equally strong go-to-market mechanisms and a story that’s compelling outside Korea.

What would change the equation for Pangyo’s global reach

Cross-border capital and talent should be flowing earlier. Co-investment vehicles with foreign funds, more growth-stage capital from institutions like KDB or pension funds, and an expansion in venture debt could help companies remain private for longer as they scale overseas. Some policymakers have loosened rules around stock options in recent years; greater opportunity for alignment among repeat founders and early employees would deepen the talent bench.

Pangyo itself can evolve. Flexible leases and even more mixed-use development — housing, nightlife, culture — would help make the district feel less like a daytime office park and more like a 24/7 innovation neighborhood. International schools, founder visa programs and concierge services for foreign hires would ease friction and burnish its global cred compared with Seoul’s hotspots.

And all the ingredients are there: a world-beating chip and display ecosystem, globally relevant gaming IP, real AI credentials and a maturing cohort of experienced operators. The scoreboard that counts next is clear — unicorns generating a majority of their revenue overseas, commonplace cross-border M&A issuing forth from Pangyo and a tangible stream of global engineers and executives to boot, with companies buying or being bought. Until that flywheel starts to turn, South Korea’s “Silicon Valley” will be an impressive national cluster but one that still falls short of a true global cluster in the making.