After years of scattered save files and duplicate ROMs strewn in disarray across phones, tablets, and laptops I use for retro gaming, I finally yanked my library into a single space that rarely lets me down: my NAS, facilitated by a self-hosted browser-based emulator stack. In other words, it quite neatly fits all the relevant game hardware (and software) into another computer running in your home.

The end product is what I always hoped retro gaming in 2025 would look like: one library, one set of saves, and play anywhere with zero device-specific setup.

- How Browser-Based Emulation Has Solved My Sync Headaches

- How the NAS Setup Actually Works for Your Emulator

- One Library to Rule Them All (With Caution, of Course)

- Play Anywhere With a Controller That Works

- Where the Limits Are, and Where There Are Smart Alternatives

- Retro Fans Rejoice: Centralized NAS Emulation Made Simple

If that sounds elementary, just think how frequently modern life can jostle you between screens. A report from Deloitte’s Digital Media Trends confirms that US homes juggle well over 20 connected devices, and frankly fragmentation like that is brutal to emulate. Putting ROMs and the emulator runtime on the NAS solved my biggest headache—sync.

How Browser-Based Emulation Has Solved My Sync Headaches

With traditional setups, that would be one emulator build per device, conflicting configurations, and saves drifting out of sync. Cloud folders helped but added conflicts and path bullshit. The equation shifts when the emulator is hosted inside the browser: game, save data, and config live on the server; every device is a thin client.

The stack that I am using combines several cores which are run in the browser with Nostalgist.js, using up-to-date WebAssembly for near-native performance on 8- and 16-bit platforms. That means no picking which device to download to, no version mismatching, and none of that “which laptop has the latest save” thing. Open the link on your home network and continue right where you left off.

How the NAS Setup Actually Works for Your Emulator

Deployment was blessedly simple: a docker compose file, a lib folder on the NAS, and a quick env pass for storage paths. On an x86 NAS with hardware virtualization enabled, it will take around 20 seconds from pulling the image to the web UI starting. You can also go with a hosted account if you’re not in the business of running your own infrastructure, but self-hosting keeps everything under your roof on your LAN—no hopping over an ISP or using some third party’s web service for higher latency and more privacy.

I sorted ROMs by platform, then region, and retained verified hashes using No-Intro and Redump naming conventions to minimize the likelihood of mismatches. ROMs over a gigabit LAN load in a heartbeat—most 8/16-bit titles are sub-5MB—and input lag isn’t really an issue for 2D consoles. I allowed access to the service only on my internal network and linked it with my existing reverse proxy so I could optionally connect to it off-site using 2FA.

One Library to Rule Them All (With Caution, of Course)

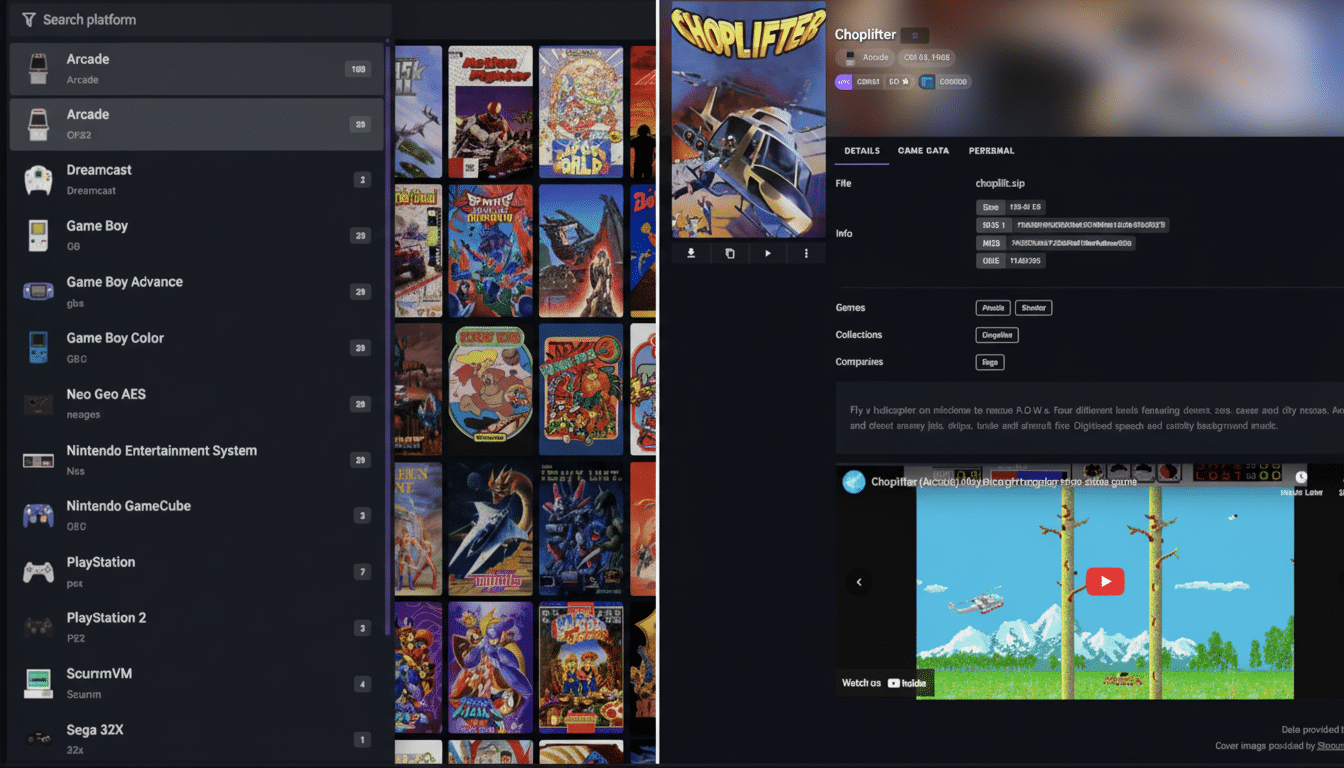

When the ROMs arrived, the platform scraped for box art, publishers, release years, and screenshots from my collection of Game Boy, SNES, and others.

It’s a simple gesture that has a big impact—a wall of filenames becomes something you can browse. Even with a library of 300–500 titles, visual aids and developer info will slash search time.

File naming is matched against metadata and hashes, so spend an hour cleaning up names for returns. I also applied series and genre tags, which can help surface forgotten gems. Storage overhead is negligible—images consume a few hundred megabytes at most, which is hardly noticeable on typical modern NAS volumes.

Play Anywhere With a Controller That Works

Dead set against touch-screen overlays, though they’ve been fine in a pinch; I prefer hardware. My ASUS ROG Kunai 3 connected over Bluetooth and was properly mapped out of the gate, a rarity when working with most mobile emulators. (My 8BitDo pad and DualSense both “just worked,” detected immediately, with remapping per core.)

On a TV, I boot from a lightweight browser on a set-top box and keep playing the same save I started on my phone. This continuity was the crux of this whole undertaking, and it delivers: same ROM, same runtime, same everything—regardless of screen.

Where the Limits Are, and Where There Are Smart Alternatives

This works great with primitive Atari, Nintendo, and Sega systems; however, it’s not universal yet. Older 3D consoles like PlayStation 1 or Nintendo 64 are not well supported in the browser-first stack, because it probably doesn’t have enough power. There may be more platforms coming now that BIOS is supported in a new major revision, but it’s not there yet.

Multiplayer is also single-system at this point; couch co-op hopefuls should manage expectations. For broader platforms, and for those who don’t mind a little tinkering, the RetroArch Web Player or WebRetro cover more systems. As a starved one-man front end for library management, RomM is superb; device sync is still in its infancy, but this one is one to watch.

(A legal disclaimer: Only use ROMs you own, and if necessary, dump your own cartridges.) The Entertainment Software Association has been unambiguous about the boundaries here; backing up games you own and archiving original copies is the way to go.

Retro Fans Rejoice: Centralized NAS Emulation Made Simple

Retro gaming became effortless for me once I centralized emulation on a NAS. The browser-based stack crammed years of sync pain into one library with shared saves, clean metadata, and controller support that simply worked. It’s not the solution for every system yet, but for 2D consoles it’s fast, friendly, and rock-solid—exactly the sort of upgrade that makes nostalgia a nightly habit.