Security researchers say an attempted disruption of Poland’s power network was carried out by a Russian state-backed hacking unit long linked to sabotage of energy systems, underscoring the escalating cyber pressure on Europe’s critical infrastructure.

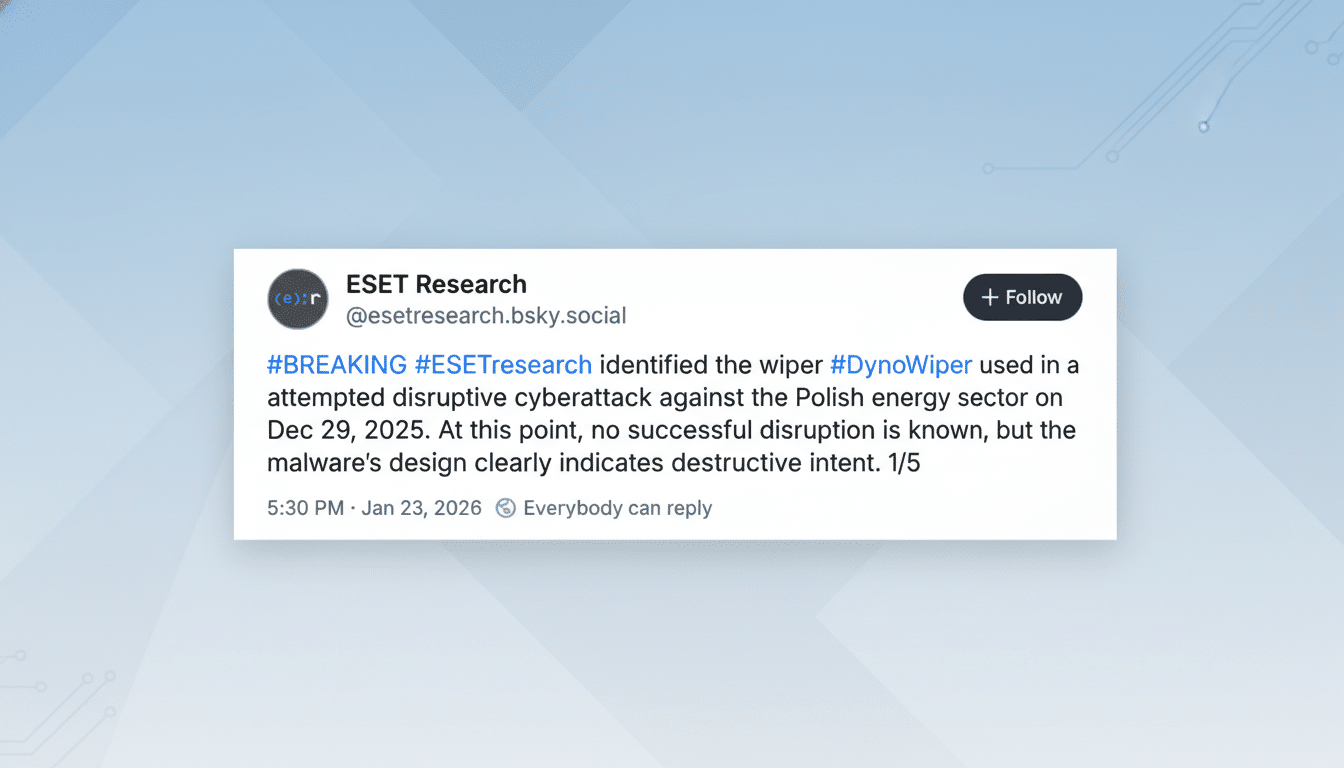

Analysts at ESET examined destructive code recovered from the failed operation and identified it as a new strain of “wiper” malware they call DynoWiper. The firm attributes the campaign with medium confidence to Sandworm, the notorious team within Russia’s military intelligence agency believed responsible for multiple grid attacks in Eastern Europe.

Polish officials have described the incident as the most serious strike on the nation’s energy infrastructure in years. While defenses held and electricity service continued, authorities said the attackers probed combined heat-and-power facilities and tried to disrupt communications between renewable installations and distribution operators, a tactic designed to magnify instability.

What Investigators Found in the Poland Grid Attack Probe

ESET’s analysis points to tooling and tradecraft that strongly echo Sandworm’s past operations, including the use of custom wipers to render equipment inoperable and impede recovery. Wipers don’t steal data; they overwrite or corrupt it so systems cannot boot or control software cannot run—an approach optimized for fast, visible impact.

Investigative journalist Kim Zetter first surfaced details of the malware, noting overlaps with earlier Sandworm campaigns against energy providers. Those overlaps include code similarities, deployment methods, and the targeting of operational technology (OT) environments where small missteps can have large physical consequences.

Local reporting in Poland indicated that, if successful, the attack could have cut heat and power to roughly 500,000 households. Prime Minister Donald Tusk said national cyber defenses functioned as intended and that critical infrastructure was not put at risk.

How the Attempt Targeted the Grid and Renewables Links

The operation appears to have unfolded on two fronts: direct targeting of generation assets and interference with the control-plane connecting distributed renewables to grid operators. The latter is a growing attack surface as utilities integrate thousands of wind turbines, solar parks, and battery systems that rely on supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) links.

In European power systems, telemetry and commands often ride over protocols such as IEC 60870-5-104 and Modbus. Prior Sandworm-linked efforts have sought to abuse these channels—either by sending malicious commands or blinding operators to real-time conditions. Cutting visibility can force operators into conservative, manual modes that reduce available capacity and raise the odds of localized outages.

Poland’s grid operator PSE has warned that the rapid spread of distributed energy requires tighter identity controls, segmentation between IT and OT networks, and robust incident response playbooks. With coal still supplying about 65% of Poland’s electricity and renewables growing quickly, the blend of centralized plants and far-flung assets demands layered defenses.

A Familiar Adversary With an Energy-Sector Playbook

Sandworm, tracked by Mandiant as APT44, has a documented history of targeting power infrastructure. Nearly a decade ago, the group helped orchestrate blackouts in Ukraine by compromising utility control rooms and deploying destructive malware, cutting electricity to more than 230,000 customers. A follow-on campaign introduced CrashOverride/Industroyer, the first malware designed specifically to manipulate grid protocols.

Since then, Russian-linked actors have repeatedly fielded wipers—HermeticWiper, CaddyWiper, and others—against Ukrainian organizations. The pattern is consistent: destroy backup systems, corrupt workstations that engineers rely on, and, when possible, tamper with devices that move electrons, water, or rail traffic in the physical world.

Why Poland Withstood the Hit on Its Energy Network

Poland’s resilience likely reflects several factors: improved network segmentation between corporate IT and plant OT, unidirectional gateways on critical links, multi-factor authentication on jump hosts, and tighter vendor access controls. Routine “tabletop” exercises and the proliferation of out-of-band backups also reduce the bite of wipers like DynoWiper.

National and EU-level rules have raised the bar. NIS2 and the Critical Entities Resilience framework push operators to harden identity, logging, and incident response across supply chains. CERT Polska and sector-specific teams regularly share indicators of compromise and test contingency plans, helping utilities detect and eject intruders before they can escalate.

What This Means for Europe’s Energy Security

The attempted disruption in Poland underscores a strategic reality: as Europe decarbonizes, the attack surface grows. Thousands of grid-edge devices, inverter-based resources, and remote substations widen the aperture for adversaries skilled at moving from IT to OT environments.

Experts point to several priorities. First, continuous monitoring of OT networks with anomaly detection tuned to power-system physics. Second, rigorous testing of failover procedures that keep heat and lights on even if control systems are degraded. Third, supply-chain scrutiny of firmware and management software used by integrators and OEMs.

For now, Poland’s defenses held and the lights stayed on. But the emergence of DynoWiper and the renewed focus on renewable control links suggest adversaries are refining their playbooks. The next wave may come faster, hit more targets simultaneously, and aim beyond mere disruption toward eroding public trust in the grid itself.