A powerful U.S. pilots union is urging federal regulators to reject an air-taxi start-up’s proposal to use small drones to drop ball-shaped containers of pyrotechnic solution from the sky and set off cloud-seeding flares, arguing that the plan violates safety rules designed keep aircraft with pilots aboard safe from hazards such as lasers, hazardous materials and uncrewed aircraft.

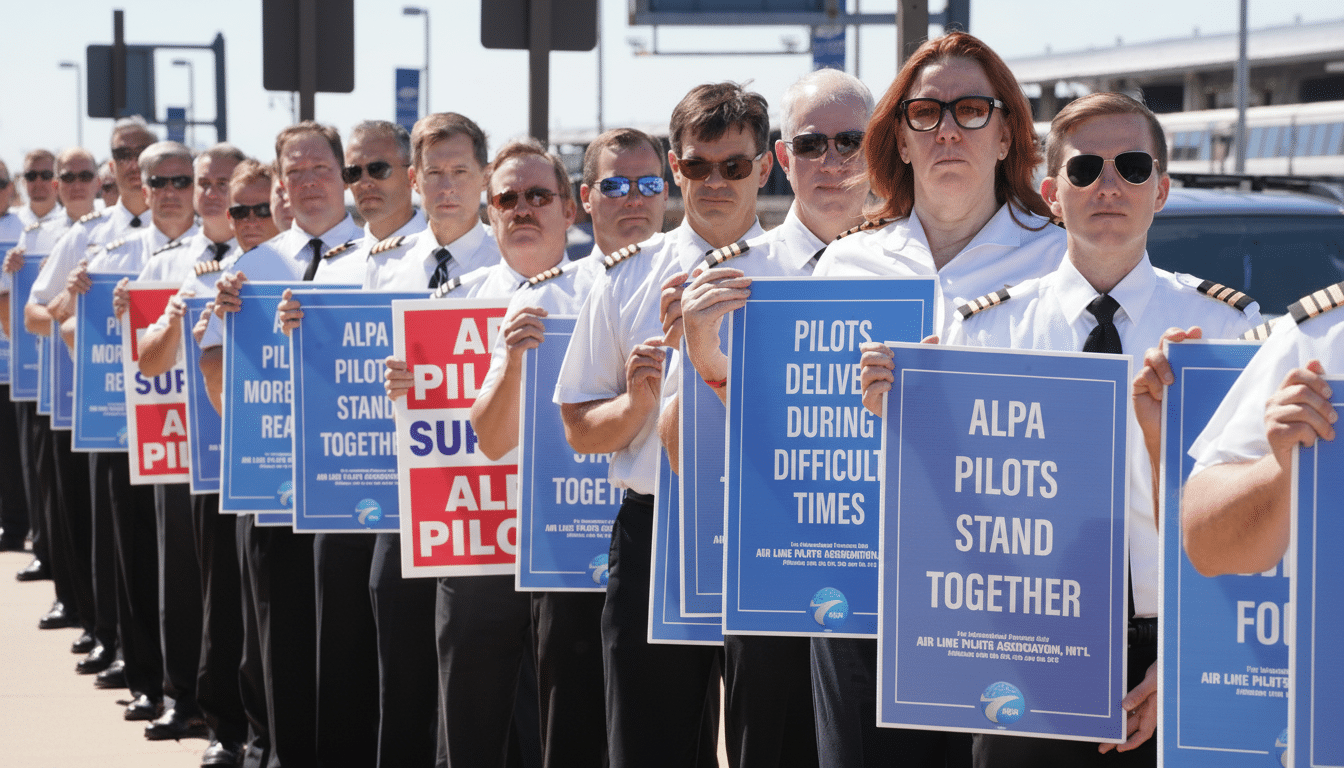

The Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) said Rainmaker Technology’s request “does not show an equal level of safety” and urged the FAA to deny its exemption unless the company met even tougher protections. The request falls at the intersection of two heavily regulated areas: unmanned aviation and weather modification.

What the pilots are arguing against

Rainmaker is seeking relief from rules prohibiting small uncrewed aircraft from carrying hazardous materials, which include the flare cartridges used to dispense seeding agents. The company plans to attach two types of flares, “burn-in-place” and ejectable, to its Elijah quadcopter in order to release particles capable of seeding precipitation.

ALPA’s filing mentions several risks: the fire hazards of pyrotechnics going off, foreign object debris recorders flowing from spent casings into engines lying just feet away, the uncertain trajectories for ejected components along populated shorelines and white-capped water with swimmers in it, and operations in controlled airspace where commercial airline traffic is heavy and weather conditions often are instrument-only. The union also highlights absence of public modeling on how ejecta would fall or chemicals disperse.

Operating height is at the heart of the concern. The platform, according to Rainmaker, is designed to reach as high as 15,000 feet mean sea level (MSL), firmly occupying space in the same airspace used by commercial and cargo flights. Under current rules, small drones are generally limited to 400 feet above the ground and need specific authorization to enter controlled airspace; waivers for transporting hazardous materials carry further restrictions.

Rainmaker defense and proposed mitigations

Rainmaker says the union is operating on an incomplete public record. Executives contend detailed risk analyses and mitigations were laid out in confidential materials submitted to the F.A.A., including procedures to coordinate air traffic, use a certified remote pilot, real-time observers and electronic aids that could help avoid collisions.

The company characterizes its flare work as research done in controlled settings and is moving to a proprietary aerosol system that only deploys silver iodide. In a normal mission, Rainmaker said, some 50 to 100 grams of silver iodide are released — quantities the company maintains are minimal compared to what crewed aircraft at altitude emit by routine.

Rainmaker also says that flights will be over rural areas and private land with landowner agreements and advanced coordination, using broadcast notifi cations. That approach, the company says, minimizes bystander exposure and eases the deconfliction of airspace.

The effectiveness — and limitations — of cloud seeding

Cloud seeding is hardly new. Western water agencies and ski areas have hired crewed aircraft to seed winter storms for decades, typically by spraying silver iodide into a storm to encourage ice crystal growth. States with programs in place, like Utah, Colorado, Nevada and Idaho, typically operate through coordination with state officials and local air traffic control.

Scientific evidence indicates modest gains can occur under certain circumstances. The Wyoming Weather Modification Pilot Program found small increases in snowfall from seeded clouds, but with much uncertainty and variation from event to event. The National Academies of Sciences has consistently urged stronger, randomized evaluations to nail down efficacy and environmental impacts.

On safety and the environment, many state reviews and past federal evaluations have not found significant harms at levels typically used, but that varies by setting. ALPA’s concern is less over silver iodide per se than the introduction of pyrotechnics and ejectable parts into what it says is airspace in which the standards for ‘detect-and-avoid’ technology to be deployed on small drones are not yet set.

The regulatory needle the FAA has to thread

The F.A.A. confronts a familiar trade-off: allowing for innovation while maintaining a single safety bar. Part 107 expressly prohibits carriage of hazardous materials for small UA, and operations beyond the limitations set—greater than 400 feet high above ground level, beyond visual line of sight, or in controlled airspace—are subject to explicit FAA authorization followed by stringent mitigation measures.

To placate the agency, Rainmaker will likely have to prove: workable containment or trajectory control over any ejectables; geofencing and altitude limits that prevent drones from entering airways; coordination with air traffic control including clear procedures for notification; end-to-end risk modeling around ignition, misfire, and loss-of-link scenarios. There is environmental documentation — frequently consulted along with the state resource agencies and, in appropriate cases, the EPA.

And the stakes are larger than any single start-up. If successful, the petition could open a potential avenue for unmanned weather modification work on, moving some cloud seeding away from manned aircraft to drones. If denied, it would solidify the FAA’s historical concerns over pyrotechnic deliveries and hazardous carriage by small UAS.

Why pilots are resisting now

Pilots maintain the status quo already permits cloud seeding with trained crews, proven aircraft and infrastructure coordination and that shifting the activity to drones equaling a few small guns in an artillery war adds new safety variables without clear safety parity.

The union’s central message is simple: new benefit claims require equivalent or better risk controls in shared airspace.

For Rainmaker and the rest of the drought-afflicted West — where states and water districts have added to seeding budgets in recent years — the result will indicate how far unmanned aviation can fly in the climate and water realm. The F.A.A.’s response is expected to help establish policies about when, how and under what conditions drones can be used as weather tools near among the country’s busiest corridors of air travel.