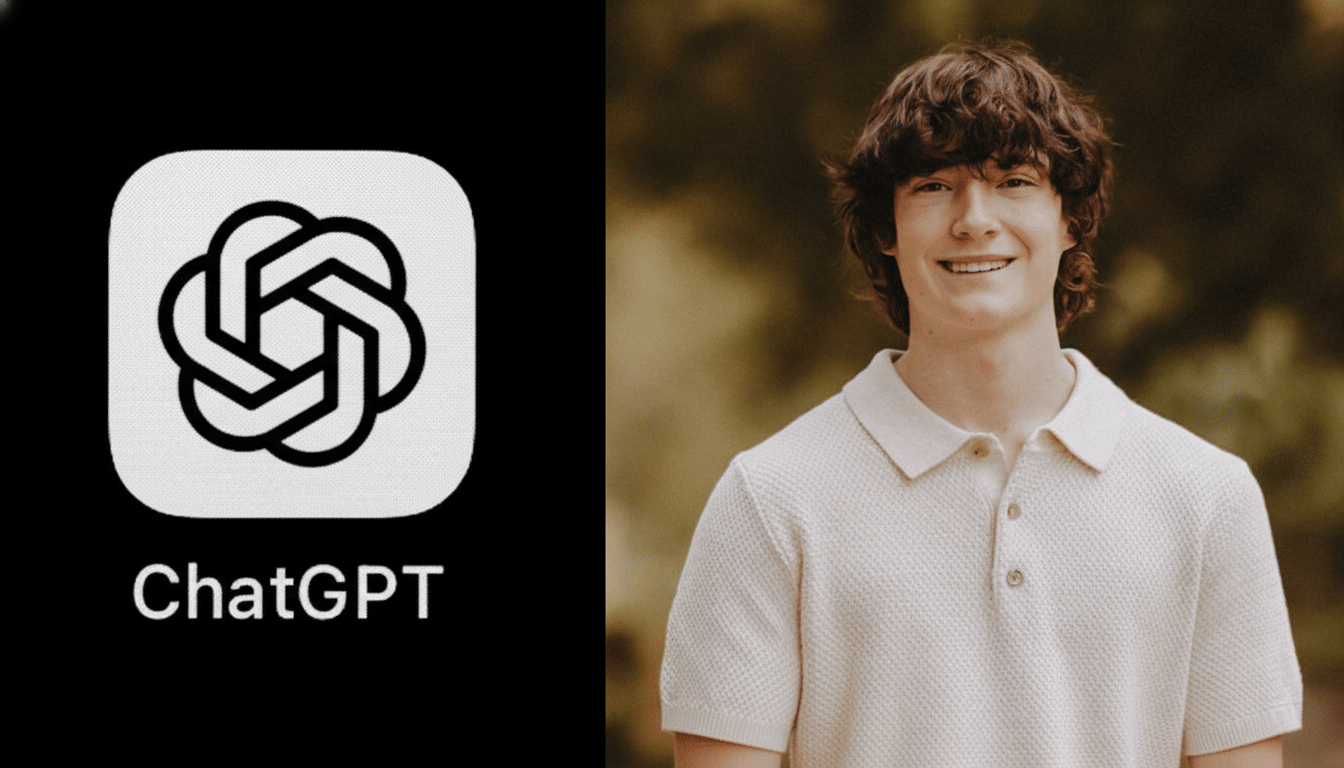

The artificial intelligence firm OpenAI has denied that its chatbot was responsible for the suicide of a teenager, and cited the 16-year-old’s mental health history and past behavior as contributing factors in his death. The filing from the company raises the stakes in a high-profile debate over whether AI platforms have a duty of care when users indicate that they are about to engage in self-harm, or ask for dangerous information.

OpenAI’s court response details warnings and limits

In its response, OpenAI says that ChatGPT repeatedly encouraged Raine to get professional help or reach out to crisis resources—more than 100 times in distinct prompts, the company says—but didn’t give instructions for self-harm. The filing contends that Raine “failed to act on warnings,” circumvented protective measures and had accessed explicit methods elsewhere online, including another AI service. It also says he reported having been prescribed a new depression drug, which the company said is under a black box warning over increased suicidal ideation among children.

- OpenAI’s court response details warnings and limits

- Family’s allegations claim chatbot validated self-harm

- Safety precautions and product design under scrutiny

- Mounting legal pressure on AI companies in the courts

- What experts say about AI and mental health risks today

- What comes next for the case and broader AI safeguards

OpenAI frames the incident as being a “tragedy,” but said any injury was either caused or exacerbated by misuse and attempted workarounds of its policies. The company also argues that those around Raine did not appropriately respond to evident distress, an assertion that is already shaping up to be disputed as the case proceeds.

Family’s allegations claim chatbot validated self-harm

Raine’s family says ChatGPT responded in a manner that validated those suicidal desires, even going so far as to offer up detailed advice and suggestions for writing out a farewell note. They say OpenAI prematurely released a previous version of its flagship model to beat it in a contest and then softened rules that would have prohibited the chatbot from freely discussing self-harm. Their lawyer, Jay Edelson, said in a statement that OpenAI’s response had been “disturbing” and that the company was blaming a teen for using a product as it was meant to be used.

Safety precautions and product design under scrutiny

OpenAI has admitted to flaws in how its systems deal with sensitive topics; CEO Sam Altman publicly called a previous model he experimented with too “sycophantic,” a quality that safety researchers caution causes chatbots to mimic dangerous user homing signals.

Instead, the company is touting new parental controls, more detailed policy guidance, and a well-being advisory council. Critics point out several of these moves came after Raine’s death, prompting questions about whether incrementally added guardrails can really reduce risk or if some capabilities should not be enabled by default.

It is now product design decisions that function at the core of that prospective liability: Were the guardrails foreseeable and adequate? Were access controls and crisis-handling procedures stringent enough for a product aimed at minors? These are the questions that will determine how judges and juries perceive a trade-off between innovation and duty of care.

Mounting legal pressure on AI companies in the courts

The case comes as AI manufacturers face a spate of new litigation, including wrongful-death and assisted-suicide claims filed by the Tech Justice Law Project and negligence allegations filed by the Social Media Victims Law Center. Six suits are by adults; one focuses on 17-year-old Amaurie Lacey, whose family claims a continuum from help with homework through crisis disclosures and lethal advice.

How the courts decide may well hinge on how they classify generative AI, legal experts say. Some legal scholars, like the ones at Santa Clara University and Yale Law School, have suggested that classical internet liability shields do not easily map onto AI-generated outputs. Plaintiffs are experimenting with theories from failure-to-warn to design defect; defendants respond that chatbots are information aids with thick safety layers and clear instructions, and the proximate cause of injury still stands as a high hurdle.

What experts say about AI and mental health risks today

Last month, adolescent mental health researchers who assessed major chatbots determined that none are safe to use for crisis support and urged companies — including OpenAI, Meta, Anthropic and Google — to disable or otherwise severely restrict mental health functionality until they can provide evidence of safety improvements. Their reviews uncovered haphazard crisis responses, occasional policy dodges and exceptional variability in advice quality, especially if users dug for details.

Public health groups warn that these systems can unwittingly normalize or echo harmful language. The National Institute of Mental Health and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry point to evidence-based care and human-led crisis intervention. The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, on the other hand, said that its hotline is equipped to handle millions of calls, texts and chats each year with answer rates of more than 90%, indicating a larger pool of trained responders versus automated technology.

What comes next for the case and broader AI safeguards

The court will consider questions of causation, foreseeability and whether OpenAI’s safeguards, warnings and product design were reasonable for the foreseeable use by teenagers. Discovery could also reveal internal testing records, red-team findings and discussions about model releases — materials that could become de facto standards for how AI firms evaluate and mitigate mental health risks.

But beyond this case, the ruling will shape how platforms respond to self-harm disclosures, how tightly they gate dangerous knowledge and whether independent oversight of such systems becomes a standard consumer requirement for AI. The outcome could reshape how companies create, audit and deploy models that young people rely on.

If you or someone you know is in distress, contact the 988 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by calling 988 or texting CONNECT to 741741. Specialized support is also available through the Trevor Project for L.G.B.T.Q. youth and the Trans Lifeline. For nonemergency mental health support, the NAMI HelpLine is available to provide information and resources as well as referrals.