NASA’s first crewed trip beyond low-Earth orbit in more than 50 years is engineered with layers of protection, but there are no guarantees. Artemis II will send four astronauts on a high‑energy flight around the moon and back, combining unproven hardware in a deep‑space environment where escape options thin quickly. How the mission handles its biggest risks will shape the timetable and tactics for future lunar landings and, eventually, human voyages to Mars.

The crew — Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen — will ride the Space Launch System (SLS) and Orion together for the first time. The plan is bold by design: push far beyond Earth, then slam back through the atmosphere at roughly 25,000 mph, a velocity on par with the fastest Apollo entries. The calculus is straightforward: test what matters most with people on board, while building in smart off‑ramps if the plan frays.

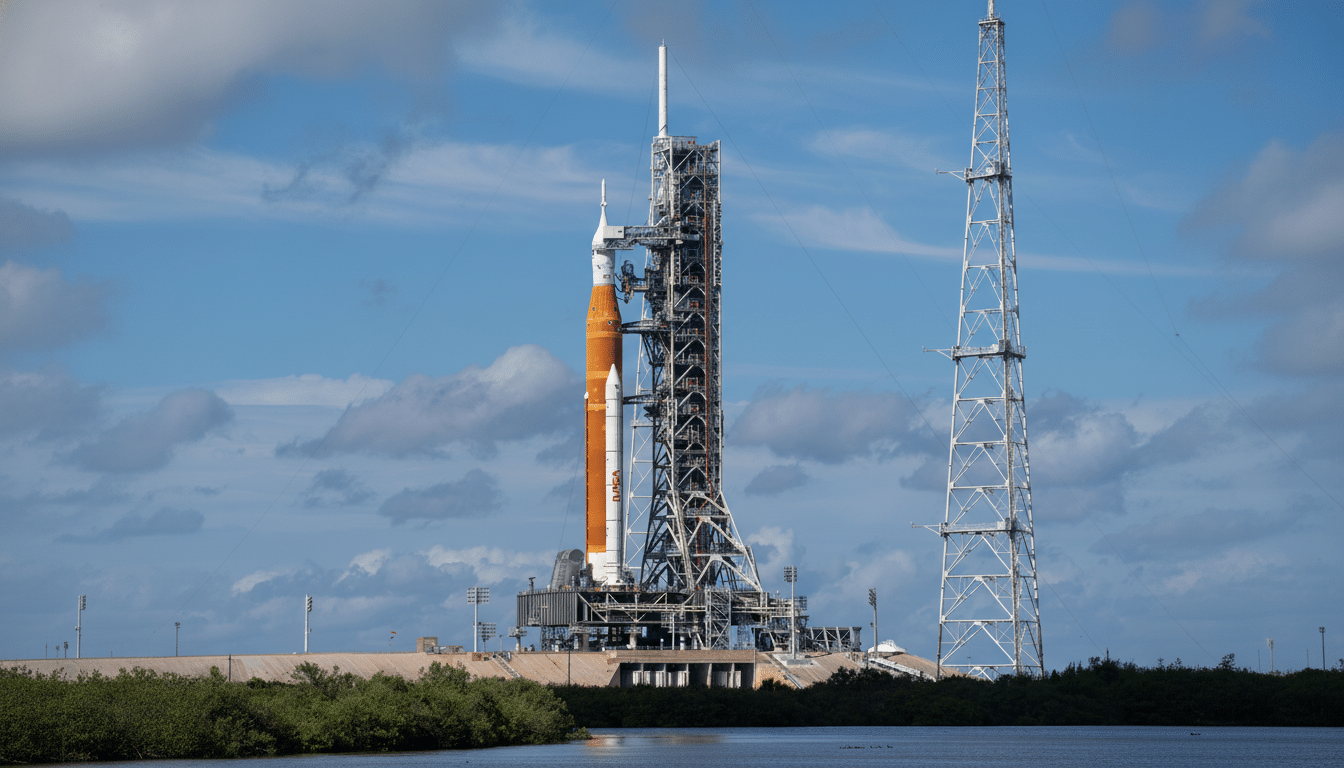

The First Crew Test of SLS and Orion in Deep Space

SLS lifts with about 8.8 million pounds of thrust, and the ascent sequence carries multiple contingencies. Orion’s Launch Abort System can yank the capsule away in milliseconds early in flight; later, controllers can redirect to a near‑term splashdown if propulsion performance isn’t nominal. After the upper stage performs the translunar burn, Orion targets a free‑return trajectory — a gravity loop that brings the crew home even if a later engine burn fails.

Those options narrow once the vehicle commits to deep space. Orion’s main engine and thrusters must execute precise flyby burns, and guidance sensors must remain trustworthy. On Artemis I, star trackers occasionally saw “nuisance” inputs from thermal effects and thruster plumes; NASA has tuned software and procedures to prevent spurious attitude updates from cascading into navigation errors.

Radiation at Solar Max Is the Wild Card Factor

Beyond Earth’s magnetic cocoon, radiation becomes a mission driver. Outside the Van Allen belts, galactic cosmic rays and solar energetic particles pose threats to both crews and avionics. Cycle 25 is in a busy phase, and forecasters at the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center expect heightened solar activity that can spike dose rates with little warning.

Orion carries dosimeters throughout the cabin and in crew suits to map exposure in real time. If space weather turns severe, the crew can build a storm shelter under the floor, packing stowage around themselves to boost shielding. Data from Artemis I — including the DLR/ISA “phantom” torsos Helga and Zohar — showed how organ doses vary by location and shielding, underscoring the value of a quickly assembled safe zone when the sun erupts.

Radiation risk isn’t just medical. High‑energy particles can flip bits in electronics. Orion is hardened and designed with fault tolerance, but mission control will be watching telemetry for anomalies any time solar monitors indicate elevated flux.

Communications and navigation gaps in lunar flyby

When Orion arcs behind the lunar far side, the crew will be out of contact for roughly three‑quarters of an hour. That blackout is planned and modeled, yet it concentrates risk: any problem that emerges there must wait for signal to return. Beyond that window, the mission leans on NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN), a global set of antennas also serving Mars spacecraft and major observatories.

Artemis I revealed the DSN’s own vulnerabilities when ground equipment failures produced an hours‑long communications loss. NASA has since refreshed software and hardware while optimizing antenna assignments for Artemis II. Still, bandwidth is finite, antennas age, and every handover is a point of failure. The program’s mitigation is straightforward: redundancy across sites, tighter alerting, and more conservative margins during critical burns.

The heat shield and the high‑energy Earth return

Reentry is the moment that keeps mission managers humble. Artemis I revealed more charring and material liberation from Orion’s heat shield than predicted, even though temperatures and capsule loads stayed within limits. NASA’s post‑flight analysis concluded the system protected the vehicle as designed, but the erosion pattern prompted changes to reduce peak heating on Artemis II.

Engineers have adjusted the skip‑entry corridor and shifted the nominal splashdown zone closer to Southern California to shave thermal stress and refine recovery timelines. The Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel has called for clear margins and test‑as‑you‑fly conditions, reflecting the reality that thermal protection is a mission‑critical, single‑point barrier. Parachute deployment — from drogues to three mains — is also a scrutinized chain; while the system performed well on Artemis I, water landings remain sensitive to winds and sea state.

Life Support And Human Factors Under Real Load

Artemis II is the first time Orion’s life‑support stack runs with a crew end‑to‑end in deep space. The air revitalization system must scrub CO2, manage humidity, and regulate temperature through sleep, exercise, and high‑stress phases, all while handling off‑nominal modes. Multiple sensors and manual backups exist, but this flight will validate how the system behaves with people generating heat and moisture far from resupply.

Human factors matter just as much as hardware. The crew will face long dynamic phases, 45‑minute comm blackouts, and tight timelines during burns. NASA’s training emphasizes procedures for building the radiation shelter, hand‑flying attitudes if guidance is degraded, and staying ahead of caution‑and‑warning cues. The U.S. Navy’s recovery team has already rehearsed capsule retrieval off the Pacific coast to cut time from splashdown to medical checks.

Put simply, Artemis II layers defenses rather than relying on any one fix: abort modes early, a free‑return path, hardened systems, a radiation safe room, and a conservative entry corridor. It’s an honest approach to a hard problem. Deep space offers no easy exits, but deliberate design and transparent risk management can narrow the odds — and teach exactly what must be strengthened before the next crew sets course for the lunar surface.