The Mob Museum in Las Vegas, the place where organized crime tells its own story, is now doing so in the server room. Its new exhibition, Digital Underworld, tells the story of how traditional rackets have developed into complex cyber syndicates by pairing historic artifacts with a live map of cyber threats unfolding around the world.

Inside the Digital Underworld at the Mob Museum

Guests are ushered through an immersive gallery where a real-time attack landscape pulses with intrusion attempts, malware beacons and suspect network traffic. Panels and interactives dissect the modern playbook: phishing and social engineering for initial unauthorized entry, data theft and lateral movement, final extortion and payment laundering.

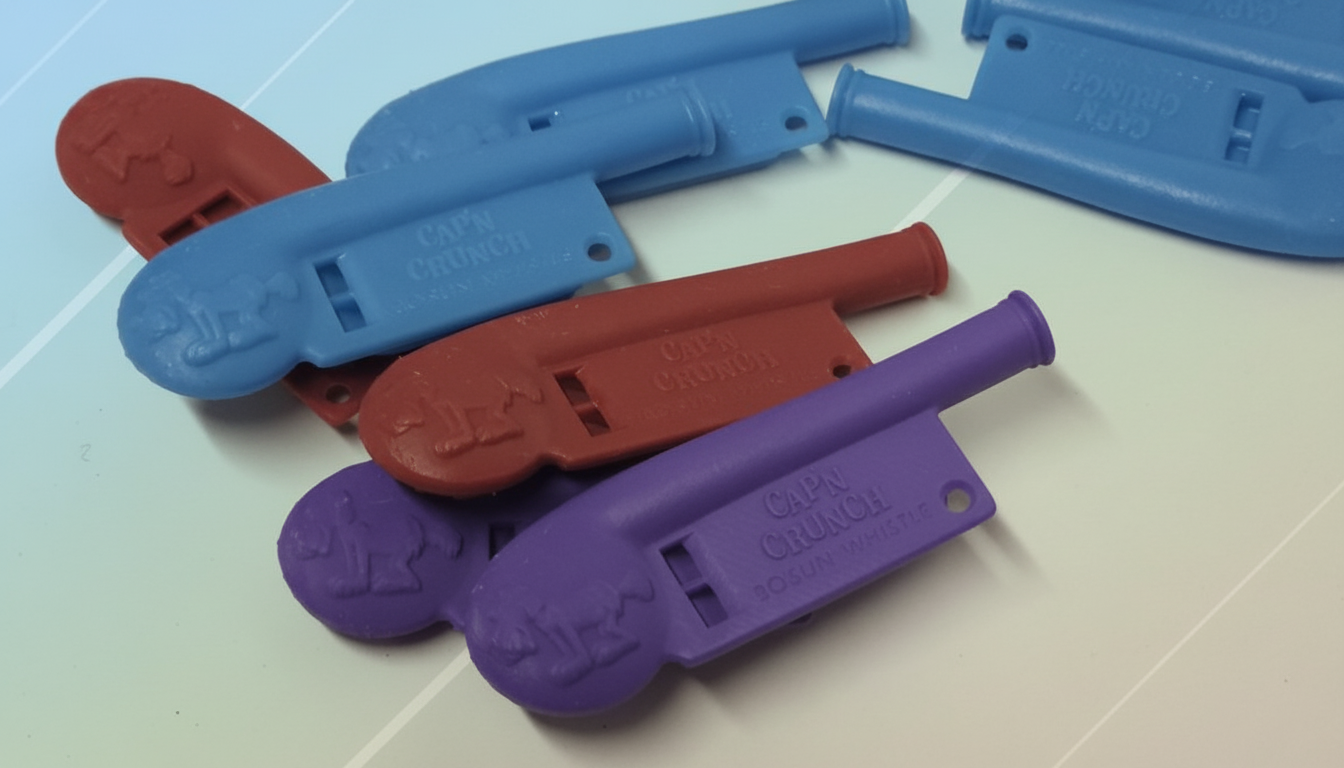

The show’s material culture pulls the tale back to digital mischief’s primal origins. On display are a Cap’n Crunch whistle that phone phreaks used to game long-distance switches; a floppy disk containing an early virus and the uncommon publication from which it was disseminated; one of many items associated with Joseph Popp’s late-1980s “AIDS” Trojan (often cited as ransomware’s first actual deployment). Together, the items form a straight line from analog pranks to industrialized crime.

From Phone Phreaks to Today’s Ransomware Gangs

Early hackers used tones and badly written phone systems. Today’s intruders phish for cloud accounts, SIM-swap targets, and compromise remote management tools. The tactics are different, but the incentives — control a network, monetize access, limit risk — reflect the logic of the old mob.

Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) cemented this evolution. LockBit and ALPHV/BlackCat are among the groups that work much like franchises — renting code to affiliates who break in, steal data and execute the extortion play. The most devastating campaigns combine social engineering with technical abuse before proceeding to double or, in some cases, triple extortion by menacing customers, partners and regulators.

The Math Behind the Rise of Organized Cybercrime

The scale is no longer abstract. Losses reported from cybercrime exceeded $12.5 billion in its most recent annual figures, the F.B.I.’s Internet Crime Complaint Center found, with business email compromise topping the list of the most profitable types of attacks for criminals. Ransomware payments totaled about $1.1 billion in a recent year, according to Chainalysis — an all-time high and evidence of just how lucrative the model has become despite heightened defenses and takedowns.

Breaches are also becoming more expensive to recover from. IBM’s recently released Cost of a Data Breach Report puts the average breach at just under $4.9 million considering detection, response, downtime and recovery costs. The human element of phishing clicks, credential reuse and simple misconfiguration still comes out on top for Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report year after year, a reminder that cybercrime syndicates are just as adept at hacking humans as they are code.

Threat watchers like Europol and Interpol describe a highly professional ecosystem: Developers produce the malware, then initial access brokers sell footholds; money mule and OTC crypto networks launder proceeds; “bulletproof” hosting operators and proxy services protect infrastructure. The result: a vibrant marketplace that looks and acts like organized crime, except it’s all digital.

Las Vegas Lessons from Recent Casino Cyberattacks

Digital Underworld hits awfully close to home. Top-tier breaches at Strip operators shut down reservations, slot systems and loyalty programs after the exploitation of help-desk social engineering to reset credentials that was followed by ransomware. One company said it took a nine-figure hit to profit and another is rushing to shell out an enormous ransom — textbook cases of how quickly digital strikes can turn into physical and financial headaches.

The exhibit’s local framing matters. Hospitality and gaming marry operational tech with sprawling IT, vendor integrations, and huge customer data sets — exactly the right mix for modern crews. By hanging real-time threat telemetry on the walls, the museum connects the dots between invisible packets and visible fallout on hotel floors, casino cages and back-office ops.

How Organized Cybercrime Operates Behind the Scenes

What was once a crew in a backroom is now a supply chain. A typical operation is kicked off with stolen credentials from a phishing kit or dark web market. Access is resold, a ransomware affiliate moves through the network with off-the-shelf tools, data gets exfiltrated to cloud repositories and an extortion portal posts “proof of life.” Collections are laundered through crypto mixers, prepaid cards and synthetic identities before resurfacing as funds that look clean.

Some crews keep playbooks and even service-level promises to affiliates who push their fraudulent offers, not to mention “customer support” chat sessions to create payment relationships. That corporate façade — tiered pricing, onboarding guides, bug bounties for malware — blurs the distinction between enterprise and organized crime. It’s that kind of organizational maturity the Mob Museum has chronicled in its Prohibition and postwar galleries, here translated for the digital age.

What Visitors Will Be Treated To at the Exhibit

It’s not just artifacts; the exhibit also incorporates practical hygiene. Anticipate guidance consistent with CISA and industry best practice:

- Phishing-resistant multi-factor authentication

- Quick application of patches to exposed services

- Least-privilege access

- Network segmentation

- Offline backups that are tried out regularly

- An incident response plan that is rehearsed

Digital Underworld is doing what good museums do: Uncovering an invisible universe. By marrying history with a live camera feed of continuing attacks, the Mob Museum demonstrates how the racketeering business migrated from alleyways to APIs — and why grasping that shift is now part of routine civic literacy.