Icarus Robotics has raised $6.1 million in seed money to address what is often referred to by astronauts as orbit’s least glamorous task: the ceaseless unpacking, stowing and moving of cargo.

Its embodied-AI robots are designed to “take on this warehouse work” on spacecraft and stations, where human crews can concentrate on conducting science and exploration. The round was led by Soma Capital and Xtal, and also included Nebular and Massive Tech Ventures.

The co-founders Ethan Barajas and Jamie Palmer came up with the idea after sitting down with astronauts and flight controllers to learn about life on a day-to-day basis in orbit. The image that came into focus wasn’t a perpetuity of experiments but a rhythm of logistics. The International Space Station gets regular resupply missions from companies like SpaceX and Northrop Grumman, but crews end up doing a lot of work with soft stowage containers, tools and consumables instead of research.

Why space needs warehouse robots for orbital logistics

Logistics is the stealth tax on life in orbit. Every couple of months, some 7–9 metric tons of space stuff shows up at the ISS, in standardized Cargo Transfer Bags (CTBs). Each one has to be ticked off a list, checked over, taken out of packaging and put in an exact position somewhere. In planning memos, NASA consistently lists crew time among the scarcest resources in low Earth orbit; hours devoted to bag wrangling and inventory are hours not spent on research or technology demonstrations.

The result is a chronic depression in productivity. Even straightforward tasks — replacing a canister of fluid, preparing a climate experiment or loading materials science samples — typically require time-consuming prework to search for and fetch gear and then restore it to its place. A robot work force dedicated to microgravity logistics might increase the use of the orbital lab by removing routine manipulation tasks from the crew’s to-do list.

A practical, microgravity robot built for station work

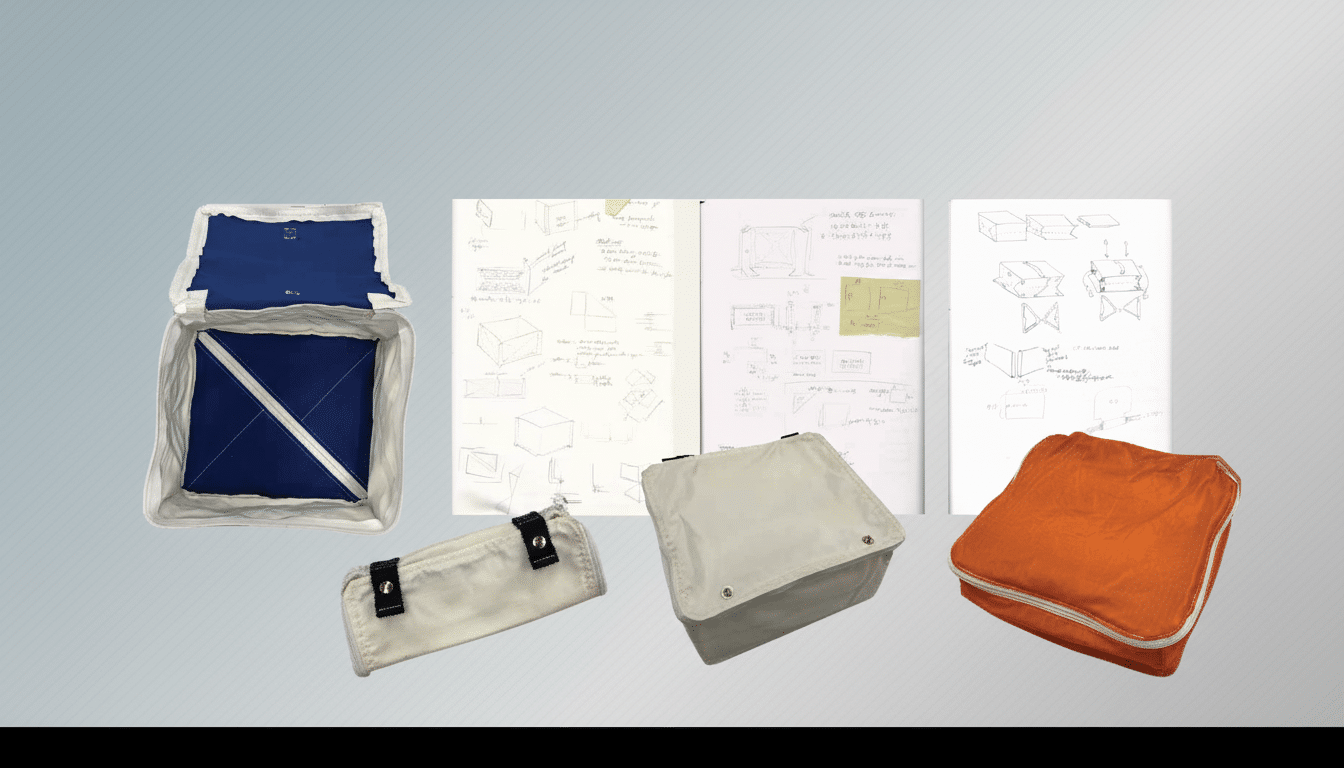

Icarus is not following the humanoid form factor. The company’s initial system is a fan-driven free-flyer with two synchronized arms and rudimentary jaw-style grippers. Palmer, a roboticist by training, says bimanual manipulation can give most of the dexterity necessary for CTB work without the complexity of anthropomorphic hands. In internal testing, the team has also unzipped a flight-grade bag, removed items from it and re-zipped it closed using long-distance teleoperation — a strong indication that high-value logistics may be accomplished with pragmatic tooling.

Microgravity changes the balance of factors in how robots move and handle cargo. In the absence of floor contact, propeller-based station-keeping offers accurate six-degree-of-freedom placement and light touch forces for gentle tactile interaction, minimizing chances of bumping delicate payloads. The jaws themselves are not dexterous theater; they prefer a wide working envelope around bag handles, zippers, toggles and standardized fixtures deployed throughout ISS modules.

From teleoperation to embodied AI for space logistics

The Icarus project paves the way toward autonomy. In the interim, they’ll be teleoperated — a decision that makes plenty of sense on the ISS, where low-latency communication makes real-time operation practical, and the “labor arbitrage” with astronaut time is strong. The company has set up flight testing via parabolic flights to iterate control loops and human-in-the-loop interfaces, as well as a yearlong onboard demonstration through Voyager Space’s Bishop airlock, with its initial focus on CTB handling and inventory workflows before growing into light maintenance activities (like seal and filter inspections).

Over time, as data accumulates, Icarus will convert teleop sessions to training fuel for more and more models of embodied AI tuned for microgravity. The idea is to move from direct control to “higher-level primitives” where the operator gives an intent — open the bag, unstow the item, check a label — and the system handles fine motion. The company’s ultimate goal is to establish fully autonomous logistics for deep-space missions, in which teleoperation would be impossible or impractical due to the time delay between Earth and Mars (or another target spacecraft), enhancing human productivity rather than replacing it.

Where Icarus fits in the current orbital robotics landscape

Icarus is being planned with a very different role from earlier station robots. While NASA’s Astrobee free-flyers are excellent monitors, mappers and inventory takers; they were not intended for dexterous manipulation at the level of CTB unbagging and re-stowing. Big manipulators like Canadarm2 and Dextre do the heavy lifting of payloads and mechanical work outside the station. And then there are the startups, like GITAI, that want to get into in-space servicing and assembly. Icarus zeroes in on an underserved niche: nimble, interior “last-meter” logistics within pressurized modules.

If the approach is successful, that addressable market could grow rapidly as commercial stations come onstream. Operators creating venues like Starlab and the other LEO destinations will be subject to the same crew-time limitations as on the ISS, but also be under pressure from space agencies and research sponsors to pack in as many experiments as possible. For this, a plug-and-play, validated logistics robot is an attractive value play.

What success could unlock for crews and station science

Transferring any part of the work to robots can have a multiplier effect: more experiments per expedition, fewer maintenance chores pushed off or done sloppily and tighter turnarounds in transit for sensitive payloads. It also gives more choices for lighter crews on long-duration missions. Autonomous logistics — developed around embodied AI, trained in LEO — could maintain vehicle order and mission readiness between crew visits, especially on platforms such as the lunar Gateway or deep-space transports.

For investors and operators, the incentive is clear: reduce the overhead of living in space. For astronauts, it means less time spent with zippers and Velcro and more time doing the kind of work only humans can do. With new capital from Soma Capital, Xtal, Nebular and Massive Tech Ventures, Icarus has a runway to put that proposition to the test in microgravity.