Astronomers have observed a long-predicted cosmic oddity: a dwarf galaxy lacking starlight — only small, gas-rich dwarfs have been seen before — with an extraordinarily low number of stars in it. Monikered Cloud-9 and visible near the spiral galaxy Messier 94, which lies some 14 million light-years from Earth, the object provides a unique, unobstructed view of the dark scaffolding that holds the universe together.

A Discovery By Way of What Hubble Didn’t See

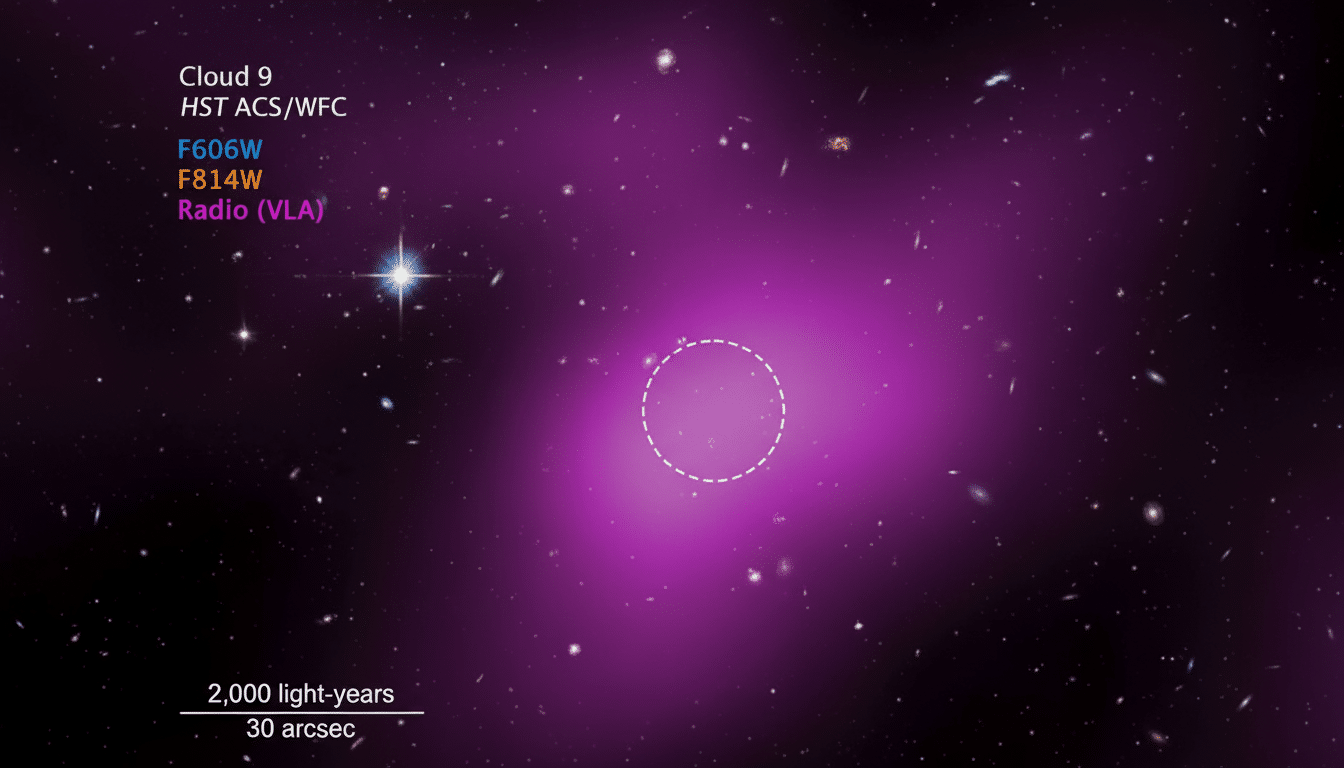

Cloud-9 was first glimpsed in 2023 as a dim reservoir of neutral hydrogen in radio data. It is some 4,900 light-years long and contains a gas reservoir equivalent to roughly 1 million Suns in mass. But radio waves alone weren’t enough to answer the crucial question: was this an ancient, faint galaxy with hard-to-see stars, or something more primitive?

To find out, the researchers pointed the Hubble Space Telescope’s Advanced Camera for Surveys at the cloud and sought the telltale glint of stars. They found none. Not some sparse array of ancient red giants, not a uniform glow — nothing. The team subsequently overlaid this result with thousands of simulated, ultra-faint galaxies inserted into the data and checked what Hubble should have turned up. Even if there had been the faintest hint of a credible stellar population, it would have shown up. It didn’t.

Published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the findings — led by researchers from the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), the European Space Agency, and Milano-Bicocca University — represent the most compelling evidence to date for an isolated, starless, galaxy-mass object in our cosmic yard.

A Window Into the Dark Universe’s Hidden Structure

Cloud-9 ought not to be held together by its gas alone; the cloud doesn’t have nearly enough mass for gravity to prevent such an airy structure from simply evaporating into space.

The simplest explanation, which accords with decades of theory, is that Cloud-9 exists within a gargantuan dark-matter halo. From the dynamics and stability of the gas, the team deduces that a further 5 billion solar masses are not visible. That suggests an intense mass-to-gas ratio and the dominance of dark matter.

According to standard cosmology, dark matter — the stuff that makes up roughly 85 percent of all matter in the universe — congregates into countless halos. Only the most massive halos are able to retain gas and cool it enough to form stars, especially after the first light sources in the universe heated and ionized the intergalactic medium. Below some critical limit, gravity loses the battle to radiation and thermal pressure — and there are no galaxies.

Cloud-9 seems to balance right on that knife’s edge. Its gas wafts through space without coalescing into a rotating disk, and there are no signs of gravitational thrashing that stars typically produce. In other words, this appears to be a “failed galaxy,” an object that stalled before the very first sunrise.

Solving a Missing Link in the Evolution of Galaxies

For many years, astronomers anticipated far more low-mass dark-matter halos than the number of dwarf galaxies observed around galaxies like the Milky Way and M94 — a long-standing mystery known as the missing-satellites problem. One possible solution is that nearly all small halos remain dark. They are out there, but they have no stars and are all but invisible except for any gas they might still possess.

Cloud-9 offers the first clear, nearby example of that population. Its properties are consistent with predictions of simulations: marginally bound, quiescent kinematics, and no stars. The object’s nearness makes it an important test for the physics that would set the threshold for star formation mediated by reionization, background radiation, and halo mass.

How Scientists Nixed Any Hidden Starlight

That’s easier said than done — ruling out faint stars. The team employed Hubble to reach levels faint enough to see individual red giant stars at M94’s distance, if they were present. They added synthetic galaxies of different brightnesses, sizes, and ages to the images to calibrate their detection thresholds. The result was clear-cut: Hubble should have seen at least a scant stellar population if one existed. It didn’t, which only bolstered the argument that Cloud-9 is really starless.

What Comes Next for Probing Starless Dark Galaxies

This discovery reveals a new observational frontier. More extensive radio surveys with existing arrays, and the SKA that will soon be available as a resource, should identify many more hydrogen-rich, starless halos in the local universe. Follow-ups from Hubble and future missions such as NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope could help to check for any stealthy starlight, reducing the distance estimate. High-resolution radio mapping will follow gas motions to more precisely weigh the dark matter halos and will probe just how closely each object approaches the star-formation threshold.

For cosmologists, Cloud-9 is an important dot on the data: evidence that some halos managed not to form stars in just this way, as theories have long suggested. For everyone else, it’s a reminder that the universe is as much the product of almosts and not-quites as its grand successes — and that every now and then the darkness itself can yield a light far brighter than the thing from which it was born.