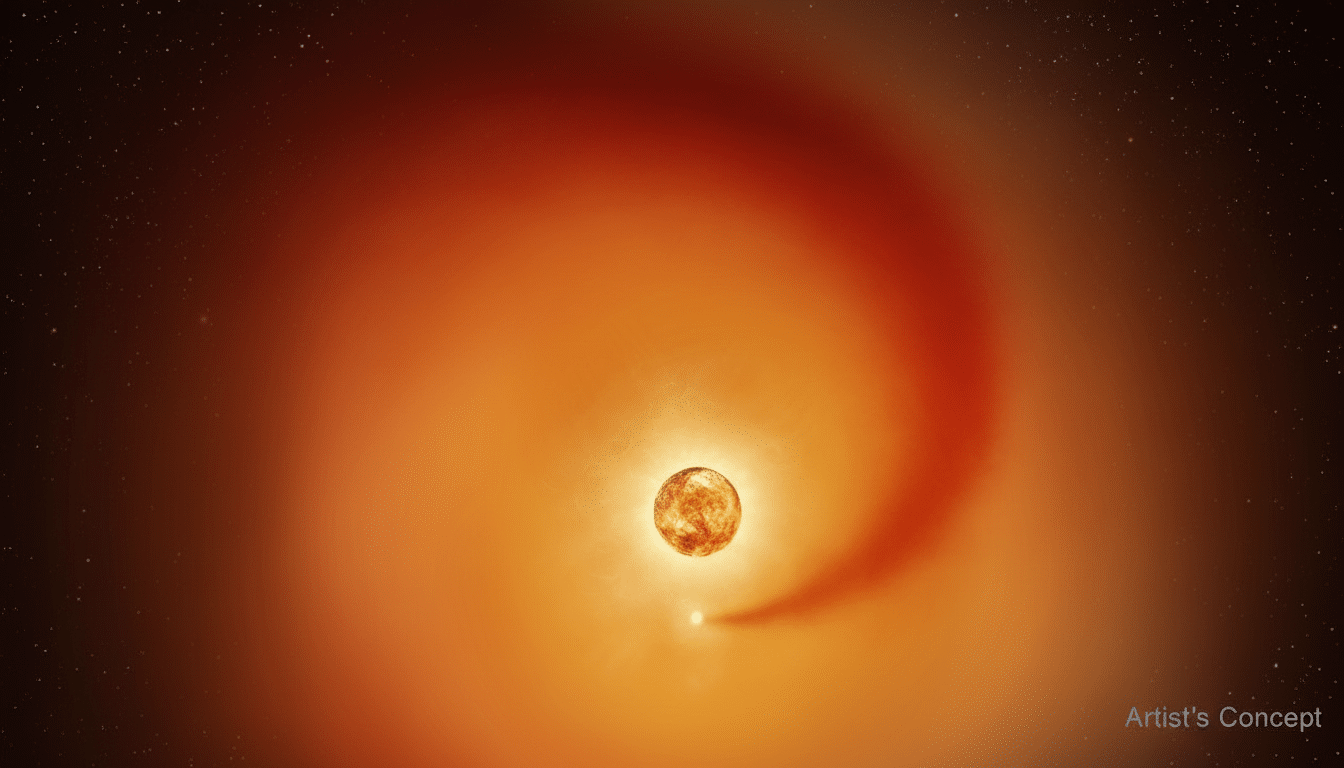

For a long time, Betelgeuse has acted like a star with something to hide. The red supergiant is roughly 650 light-years distant and cycles every six years between growing bright and then dim, a clock that never matched the standard models of aging, puffy stars. Now a new readout from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope hints at an intriguing culprit — a tiny companion traipsing through Betelgeuse’s outer atmosphere and leaving behind a suspicious trail.

Now a team led by Andrea Dupree of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics reports ripples in the star’s upper layers that bear an uncanny resemblance to turbulence in the wake of a ship.

Those ripples, recorded in starlight over eight years, coincide with the same relatively slow pulse of Betelgeuse’s throbbing, bolstering the case that the giant is part of a binary system after all.

The companion, informally called Siwarha by researchers, would be of modest size on cosmic scales — probably a smallish star — but its orbit appears so close that it never departs Betelgeuse’s atmosphere.

That close path would occasionally scrape up and shape dense, hot gas into a wake drifting across the supergiant’s face, pushing its brightness up and down from our point of view here on Earth.

Clues in a stellar wake point to a hidden companion

Ultraviolet data from Hubble is finely tuned to look for motion in the atmospheres of stars (like pulsations), and reveals where the gas around stars might be heated. In Betelgeuse, the team had found moving patches of energized gas that sweep around on the same six-year clock as the star’s global brightenings and dimmings. The signal is compatible with a dense object churning the star and squeezing material behind it — think of a speedboat wake, only on a staggeringly larger scale.

The wake grows thicker as it accumulates, darkening and intercepting ever more light, ushering in the dimmest stage of Betelgeuse. When the accumulation clears, the star brightens anew. The surface, the atmosphere and the surrounding wind appear to respond in tandem, a coherence that’s hard to wring from individual stellar outbursts but easy for a single orbiting driver.

The image fits with Betelgeuse’s history of late. During its well-publicized “Great Dimming” a few years ago, the star’s visible light dimmed by about 35 percent as a cloud of dust cooled and coalesced along our line of sight — proof that its extended atmosphere is active and easily disrupted. Yet another and more regular form of light modulation would be a companion-induced wake.

What the data shows about Siwarha, Betelgeuse’s companion

Dupree’s team suggests the companion is neither a black hole nor a neutron star: There’s no X-ray footprint to suggest accretion, and the spectrum doesn’t have the telltale signs of a compact, feeder object.

According to the standard stellar evolution, a white dwarf is also unlikely. In that case there is a relatively normal, low-mass star — perhaps half to 1.5 times the mass of the sun — doing amazing things in its position within Betelgeuse’s enormous envelope.

A tentative image of a putative companion to 51 Eri was previously reported using high-contrast techniques on the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii by a team led by NASA, but the detection was uncertain.

Hubble’s wake detection provides an alternative, independent thread of evidence: not a direct image but physical trace compatible with an embedded star in the orbit.

And angular momentum — the extent of a system’s spin — is the sticking point Siwarha helps solve. A stable, six-year modulation indicates that the “hand is on the dial” and continues moving the angular momentum around inside the envelope. Except a nearby friend can provide exactly that torque, keeping the rhythm stable even as Betelgeuse loses mass and convects wildly.

Why this matters for giant stars and binary systems

Big stars tend not to be loners.

Observations indicate that they interact with companions throughout their lifetimes, and most of the more massive ones almost certainly accrete mass or merge. But the phase during which a giant gobbles up or grazes its neighbor — known as common-envelope evolution — is famously short and elusive.

If indeed Betelgeuse is carrying an embedded partner, the star also becomes a rare natural laboratory for watching that interaction happen in real time. And the repercussions radiate across: what stirs the envelope influences dust greediness, wind geometry and hence form and asymmetries of the impending supernova. It also contributes to models of how binaries harden into compact pairs that can ultimately generate gravitational waves.

What to watch next as Betelgeuse’s suspected companion orbits

The companion is currently obscured by the glare of Betelgeuse, though astronomers anticipate a better view as it orbits further, with a possible such viewing coming in 2027.

That timeline establishes a crucial test: If the wake model is accurate, then not only should the brightness pattern, spectral ripples and infrared glow from warm dust all vary in synchrony, but they also should have predictable phase relationships.

Anticipate a synchronized campaign from observatories around the world. Hubble can still follow this as the ultraviolet wake is traced out, and ALMA can map out cooler gas, and interferometers like CHARA can resolve the evolving structure of the inner envelope in astounding detail. The analysis, which is peer-reviewed and is on its way to The Astrophysical Journal, was also shared with the American Astronomical Society — a sign that the community does see promise in pushing for a confirmed detection.

For a hundred years, Betelgeuse has been an enigma. If Siwarha is really there, detailing its wake could be the longed-for line of handwriting — the one that shows that the giant’s pulse is being watched over by a much smaller companion streaking through its immense, tumultuous atmosphere.