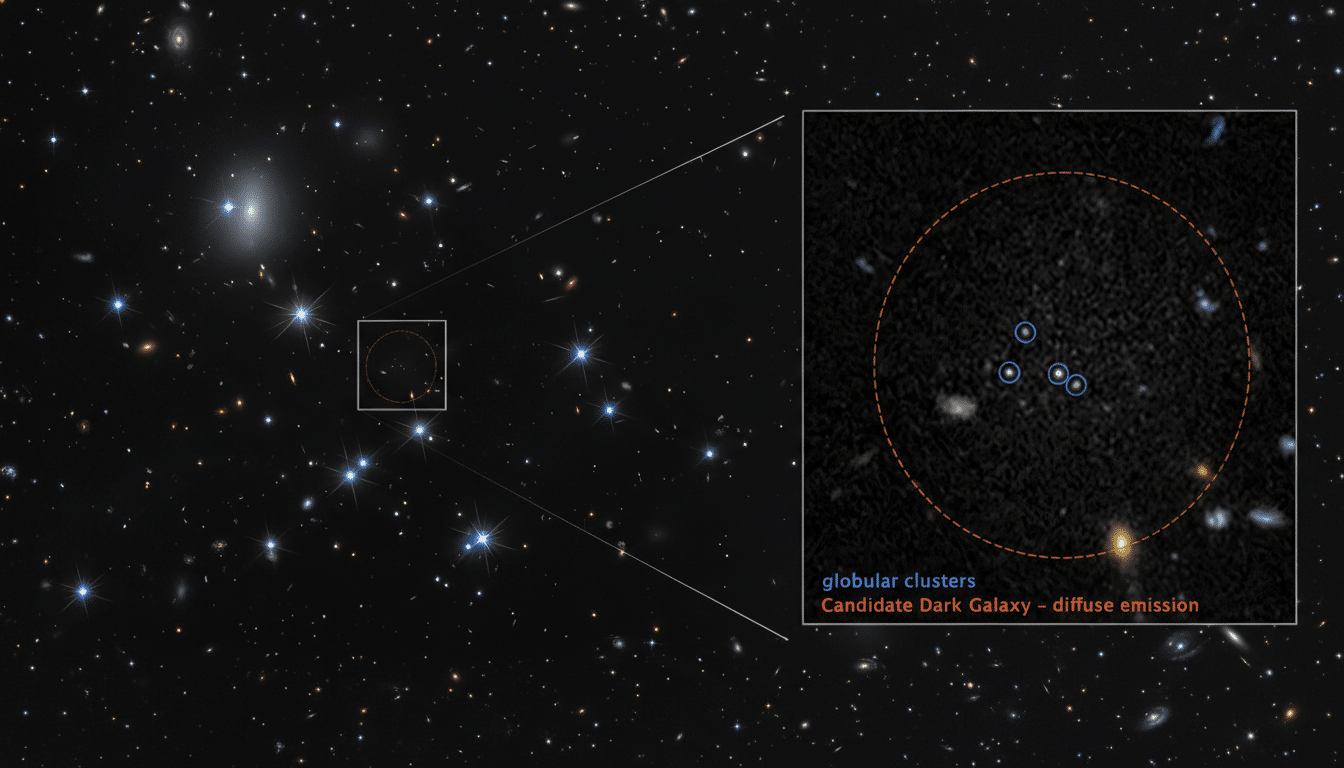

Astronomers analyzing a deep Hubble view of the Perseus galaxy cluster have uncovered a ghostly, nearly invisible galaxy that barely shines yet wields enough gravity to corral a tight knot of ancient star clusters. The object, tagged Candidate Dark Galaxy-2 (CDG-2), appears to be at least 99% dark matter, offering one of the starkest glimpses yet at a galaxy that hides almost entirely from starlight.

The discovery, described in The Astrophysical Journal Letters by a team led from the University of Toronto, leans on a rare signature: four compact globular clusters sitting unusually close together about 300 million light-years away in the Perseus cluster. Globulars typically orbit within galaxies; left to drift alone, they spread apart. These stayed huddled, implying something massive and unseen is holding them in place.

How Astronomers Caught What Barely Glows

The team surveyed images from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the European Space Agency’s Euclid observatory, and the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii. At first pass, there was no obvious galaxy—just the four dense star clusters against a mostly empty patch of space. Statistical tests showed that a random line-up of independent clusters in the same tiny area was exceedingly unlikely, pointing to a bound system.

To push deeper, researchers stacked multiple Hubble exposures, layering them to coax out ultra-faint light while suppressing noise. That effort revealed a dim, diffuse glow that matches the clusters’ position and shape—precisely what would be expected if an unseen galaxy were anchoring the group. The glow is so weak that without stacking, it effectively vanishes into the background.

Crucially, the clusters move and cluster as if tethered by a common gravitational well, behavior that is difficult to explain without a dark matter halo. In effect, the globular clusters become signposts for a galaxy that refuses to announce itself in starlight.

What Makes CDG-2 So Unusually Dark and Elusive

By the team’s estimates, CDG-2 shines with the equivalent light of roughly 6 million Suns—a pittance compared with the Milky Way’s tens of billions of solar luminosities. Yet its gravitational pull, inferred from the cluster configuration, indicates a far larger total mass. The implication is a galaxy overwhelmingly dominated by dark matter, with ordinary stars contributing only a tiny fraction of the mass budget.

CDG-2 hosts only four known globular clusters. For comparison, the Milky Way carries more than 150, while the largest ellipticals can host thousands. Sparse star formation and a meager stellar population fit the emerging picture: a system where a massive dark halo formed, but gas either never accumulated efficiently or was stripped or heated early, stunting the birth of stars.

Such extreme mass-to-light ratios are not unprecedented—ultra-faint dwarf galaxies in the Local Group, like Segue 1, also appear to be dark-matter heavy—but CDG-2 stands out for being identified first and foremost through its globular cluster architecture. It offers a complementary counterpoint to well-debated cases such as NGC 1052-DF2 and DF4, galaxies reported to be oddly poor in dark matter. Together, these outliers pressure-test galaxy formation models within the prevailing ΛCDM framework.

A New Way to Count Hidden Galaxies in Clusters

Most galaxy surveys rely on starlight: find the light, find the galaxy. CDG-2 underlines the flaw in that logic. If a galaxy emits too little light to be picked up in standard imaging, it can slip through even the most careful catalogs. Using compact globular cluster groupings as beacons offers a new route to flag such stealthy systems, particularly in crowded environments like galaxy clusters where gas can be stripped and star formation quenched.

This method also bears on a long-standing issue—the “missing satellites” problem—where simulations predict more small dark matter halos than the number of known dwarf galaxies. If many dwarfs are as dim as CDG-2, they may simply be hiding in plain sight. The approach could sharpen future tallies, bringing observations closer to theoretical expectations.

Euclid’s wide, deep imaging will be especially valuable for systematically hunting these faint halos across large swaths of sky. Subaru’s Hyper Suprime-Cam and Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys provide the high-resolution follow-up needed to confirm tight globular configurations and tease out diffuse glow. NASA and ESA missions together are building a toolkit capable of exposing galaxies that barely glow at all.

What Comes Next for This Shadowy Dark Galaxy

To solidify CDG-2’s status, astronomers aim to gather spectroscopy of the globular clusters to pin down their velocities and distances, tightening mass estimates and confirming that all four are truly bound to the same halo. Deeper imaging could reveal any additional clusters or faint stellar components, improving constraints on the galaxy’s structure and star formation history.

Researchers will also probe the Perseus cluster environment—one of the most massive nearby clusters—to assess whether tidal forces or ram-pressure stripping helped starve CDG-2 of gas. If similar cluster-tethered globular groups can be identified elsewhere, it would signal a larger population of nearly invisible galaxies, reshaping the census of the nearby universe.

For now, CDG-2 demonstrates that a galaxy can be found not by what it shines, but by what it binds. In the dimmest corners of the sky, gravity writes a story that light barely tells—and Hubble, with the help of Euclid and Subaru, has learned to read it.