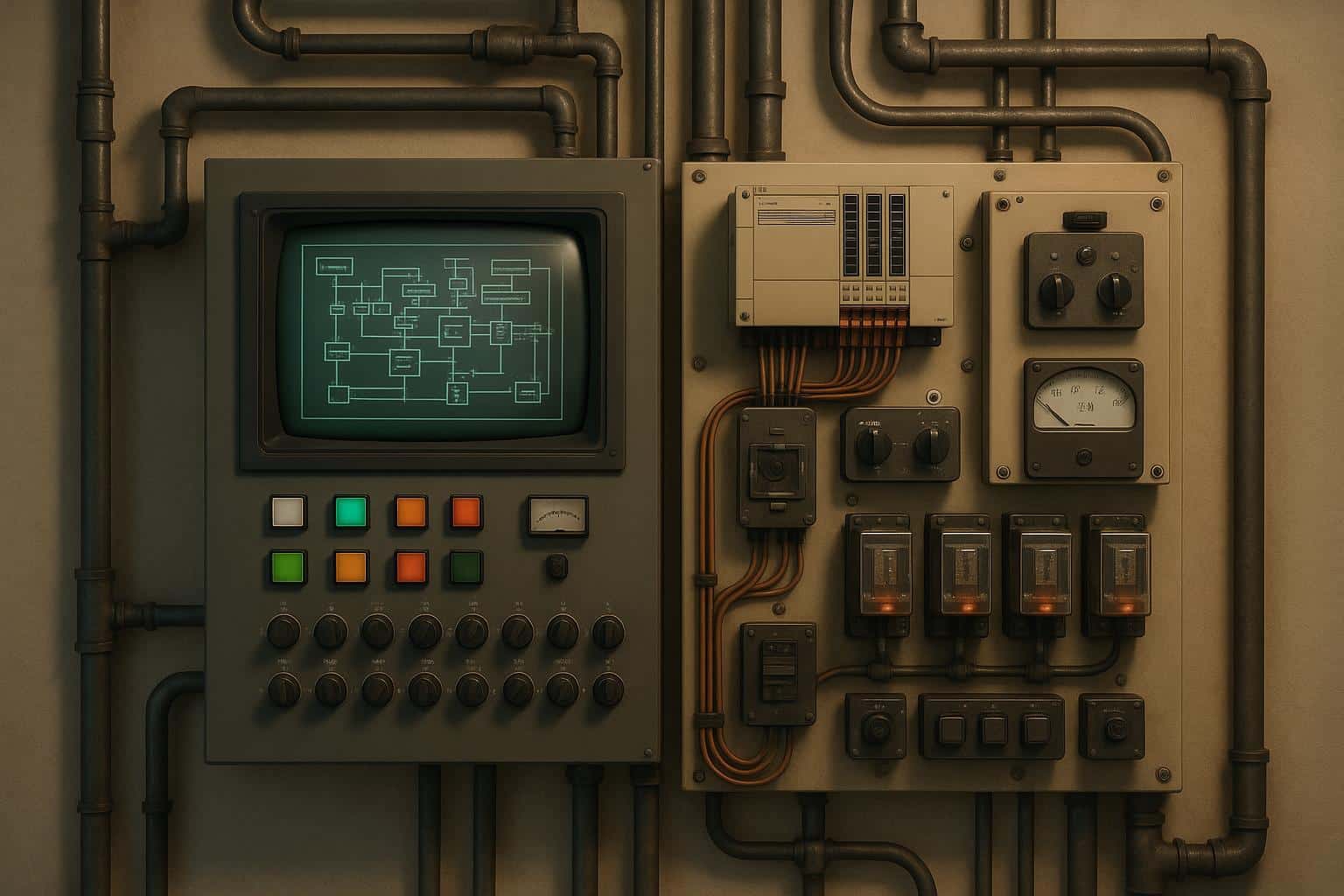

In an era dominated by headlines about generative AI and Industry 4.0, a walk through a typical manufacturing plant, power station, or water treatment facility often offers a stark contrast to the futuristic vision of technology. While the boardroom discusses cloud integration, the factory floor—the backbone of global infrastructure—frequently runs on hardware that was installed ten, fifteen, or even twenty years ago.

This creates a significant curiosity gap for outside observers. Why do multi-billion dollar enterprises, with ample capital for investment, hesitate to upgrade what appears to be “outdated” technology? Is it simple inertia, or something more deliberate?

The answer lies in engineering pragmatism. Reliance on legacy automation is rarely about a resistance to change. Instead, it is a calculated strategy that prioritizes stability, reliability, and business continuity over novelty. This article explores the hidden mechanics of the industrial world, the risks of unnecessary upgrades, and how End of Life (EOL) management keeps the lights on.

The Hidden Value of “If It Ain’t Broke”

Stability vs. Novelty

In the consumer electronics world, a two-year-old phone is considered aging. In industrial automation, a two-year-old system is barely broken in. There is a core engineering principle at play here: reliability is often proven only through the passage of time. New systems, no matter how advanced, inevitably bring new bugs and integration challenges.

Legacy Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and Human-Machine Interfaces (HMIs) that have been running for decades have survived the “infant mortality” phase of the hardware lifecycle. Engineers rely on the metric of Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF). Often, older, robust hardware architectures demonstrate a higher MTBF simply because their failure modes are well-understood and predictable, unlike bleeding-edge systems that are still being patched.

The True Cost of Migration

For a plant manager, the sticker price of a new automation system is only the tip of the iceberg. The financial burden of migration ripples through the entire operation. Upgrading a core control system inevitably leads to significant downtime, halting production lines that may generate thousands of dollars in revenue per minute.

Beyond the hardware, there is the human capital cost. Operators must be retrained, and custom code—often fine-tuned over years to account for specific machine idiosyncrasies—must be rewritten and debugged. For many firms, the risk of migration failure and extended operational pauses far outweighs the marginal efficiency gains offered by new features.

The “End of Life” (EOL) Challenge

When OEMs Move On

While sticking with legacy tech is a valid strategy, it comes with a ticking clock known as “End of Life” (EOL). This occurs when Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) cease the production of a specific component series, often to push the market toward newer product lines. This transition shifts the status of the hardware from “supported” to “obsolete.”

This creates a critical vulnerability. A factory might be perfectly functional, but if a single, discontinued circuit board or servo drive fails without a backup, the entire line can grind to a halt. The machinery is mechanically sound, but the electronic brain is irreplaceable through standard channels.

The Critical Need for Replacement Parts

Supply chain resilience becomes the primary defense against this vulnerability. Unlike mechanical parts, complex electronic components cannot simply be 3D printed or fabricated in a local machine shop. Companies must rely on a specialized secondary market to bridge the gap between their legacy infrastructure and the OEM’s new catalog.

To maintain operational uptime, procurement teams often need to source obsolete industrial components from specialized inventories rather than waiting months for a system overhaul. Having a strategy to locate these specific modules—often no longer listed in standard catalogs—is not just about repair; it is about ensuring enterprise stability.

Strategies for Sustainable Maintenance

The Circular Economy in Automation

Maintaining legacy systems fosters a circular economy within the industrial sector. Rather than scrapping tons of heavy machinery simply because the control modules are outdated, facilities can extend the lifecycle of their assets by utilizing refurbished and surplus parts. This approach is both an environmental and economic win.

The benefits of participating in this secondary market include:

- Immediate Availability: Unlike new factory orders which may have long lead times, surplus parts are often ready to ship.

- Lower Carbon Footprint: Extending the life of existing equipment reduces the e-waste associated with total system replacements.

- Cost-Efficiency: Sourcing a replacement part is a fraction of the cost of a total system migration.

Quality Assurance in the Secondary Market

A common hesitation regarding the secondary market is the fear of “used parts.” However, the modern supply chain for discontinued automation is highly sophisticated. Reputable independent distributors perform rigorous testing, cleaning, and verification to ensure that control modules and drives match factory specifications before they reach the customer.

Trust is the currency of this market. Platforms like ChipsGate bridge this gap by vetting suppliers and ensuring that critical automation parts meet the technical standards required for industrial use. This quality assurance allows plant managers to integrate replacement parts with confidence, knowing they will perform as expected in demanding environments.

Conclusion

The prevalence of legacy technology in modern industry is a feature, not a bug. It represents a commitment to stability and a recognition that in high-stakes environments, reliability is the ultimate metric. However, managing these systems requires more than just a “set it and forget it” mentality.

The future of automation isn’t just about installing the newest robots; it is about the hybrid management of reliable legacy systems alongside modern advancements. Facility managers and MRO (Maintenance, Repair, and Operations) professionals must audit their spare parts inventory before a crisis hits. Knowing where to turn when the inevitable EOL notice arrives is the difference between a minor maintenance window and a catastrophic shutdown.