Gait analysis is enjoying a moment in the sun. Strengths and limits of the technique are being reexamined after a news report that a suspect was 94 percent of a “match” to the person seen in surveillance footage from an investigation into federal bomb attacks. So what is gait analysis, and can it be used to accurately identify a person in the same way that DNA or fingerprints are?

What Is Gait Analysis and How It Is Used Today?

Gait analysis examines how people move — the length of each step, how fast they walk, the angles at which their hips, knees and ankles flex and extend; even how much their arms swing or their torsos rotate. In practice it helps orthopedists, neurologists and sports medicine specialists diagnose problems and customize rehab. In forensics it is employed to compare the gait of an individual seen in known video with that of an unknown person from a CCTV image.

- What Is Gait Analysis and How It Is Used Today?

- How Investigators Apply Gait Analysis in Cases

- Accuracy, According to Science and Real-World Tests

- Real-World Cases Show Gait Evidence Must Be Used Cautiously

- How Courts Consider Gait Evidence Under Legal Standards

- The Bottom Line on Gait Analysis as Forensic Evidence

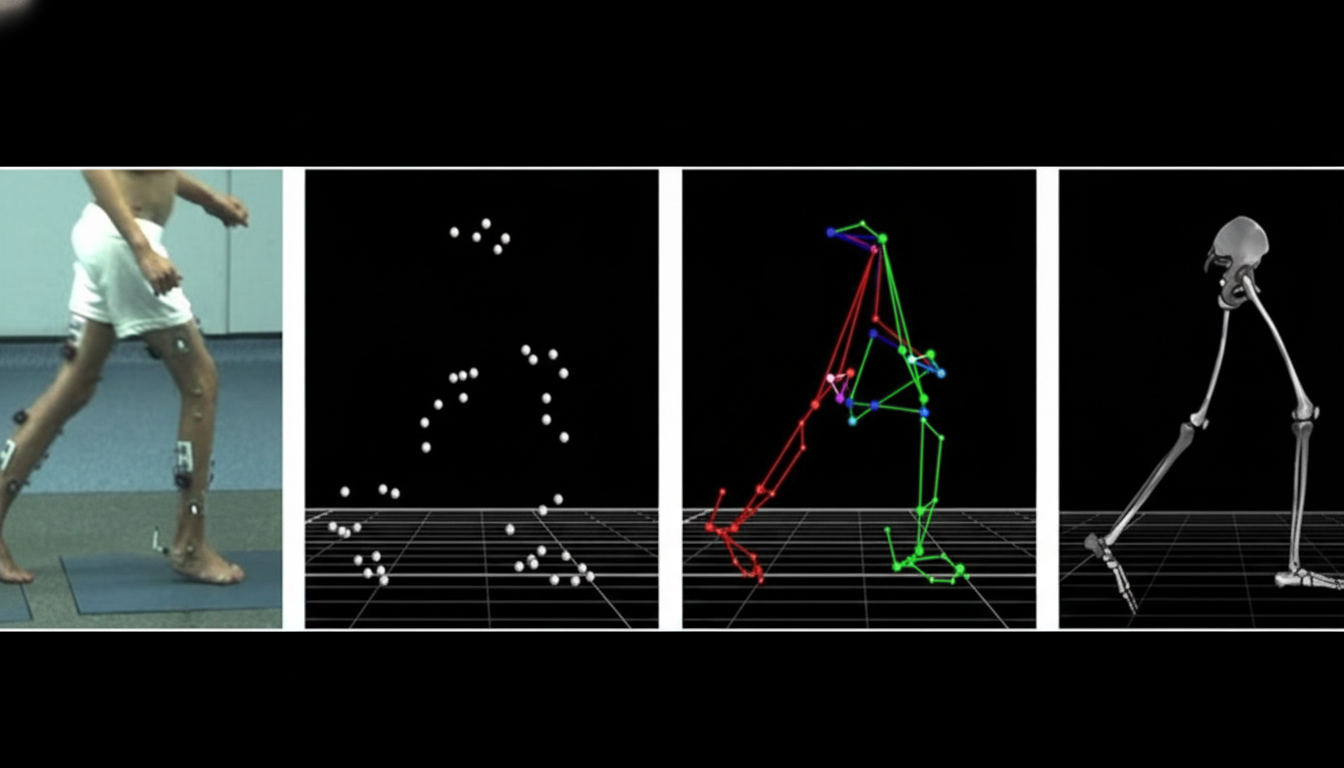

There are two broad approaches. One depends on human expert knowledge in biomechanics for the representation of visible features in ordinary video. The other relies on computer vision and machine learning to pull measurements — stride length, cadence, joint flexion — and compute similarity scores across clips. High-end motion-capture labs can measure gait exactly, but in forensic cases, that luxury is almost never available — the best case might be a super-grainy, badly angled and overcompressed security cam.

How Investigators Apply Gait Analysis in Cases

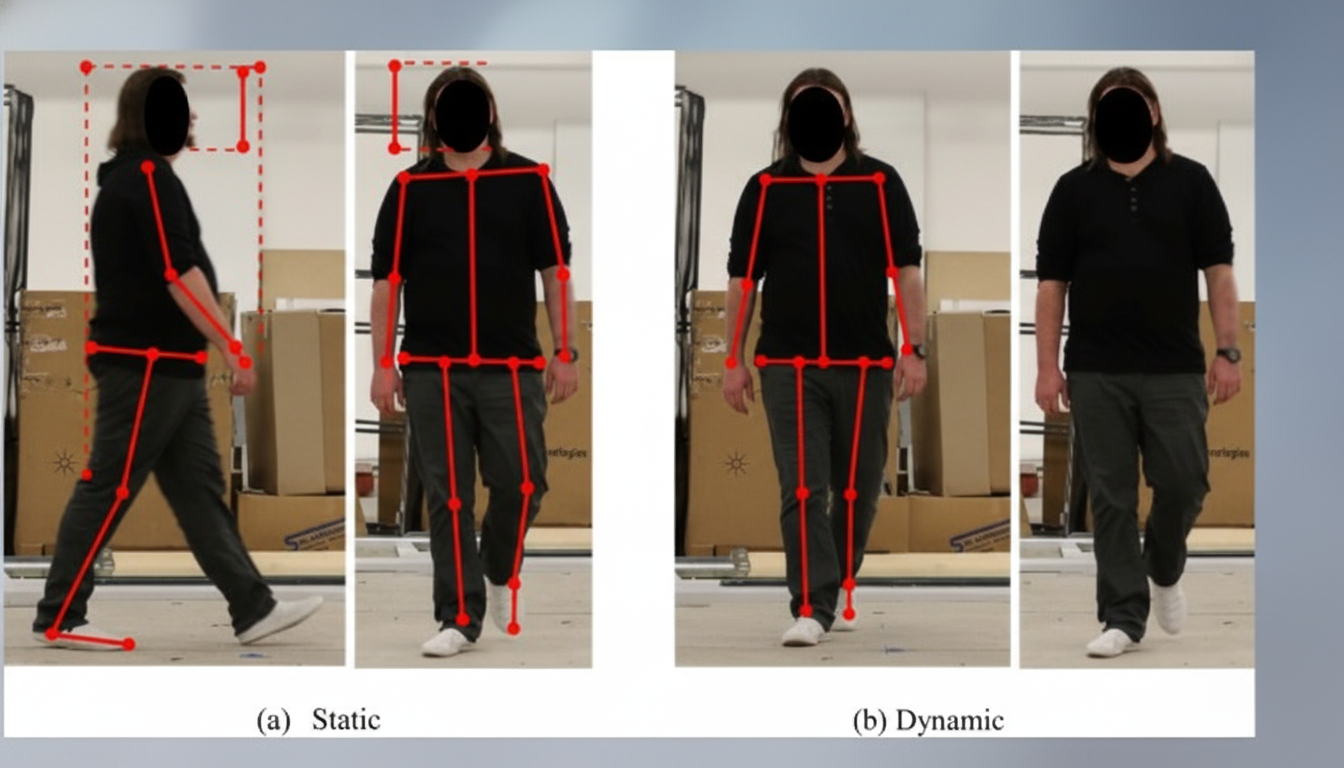

In a typical example, analysts identify the clearest sequences of the unknown walker, describe consistent features (e.g., asymmetric arm swing, toe-out angle, or decreased knee flexion), and compare those images with known footage of any person. Conditions matter enormously. Changes in footwear, a handbag, speed, surface and even fatigue can alter elements of gait, sometimes subtly, but often dramatically.

For this reason, large legal organisations treat gait carefully. Gait evidence is considered by the American Bar Association as having corroborative potential, but not to the status of being individualizing. In the UK, the Forensic Science Regulator has set guidance that restricts conclusions to evaluative language and mandates documented procedure, validated techniques and clear statements of uncertainties.

Accuracy, According to Science and Real-World Tests

Performance varies with the footage and method.

In laboratory settings, where research follows a fairly rigid structure (fixed camera locations, uniform illumination and participants who are willing to cooperate), algorithmic gait recognition boasts high accuracy rates on public datasets like the CASIA Gait Database of nearly 90 percent or even better. But that’s not courtroom circumstances.

Error rates escalate under realistic surveillance circumstances. One study, published through the Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences in 2019, found that identification accuracy was as low as 71 percent when a simulated CCTV video scenario was presented. Another piece of peer-reviewed work demonstrates that recognition falls off dramatically as clothing changes, a backpack is donned or the camera view shifts. Importantly, many studies highlight that the “uniqueness” of gait — i.e., whether it can identify one individual to the exclusion of all others — remains unresolved.

This is also why a raw “match score” like 94 percent isn’t, by itself, sufficient to support identity. Without knowing more about how the algorithm works, what YouTube data it was trained on, its known error rates and the specifics of how the two videos were compared, a high percentage can be misleading. The National Research Council’s groundbreaking report on forensic science and subsequent reviews by scientific advisors have repeatedly cautioned against overclaiming from pattern and impression evidence that does not come with reliable error metrics.

Real-World Cases Show Gait Evidence Must Be Used Cautiously

Technical glitches, however minor, can have outsized consequences. For instance, slow frame rates cause swing phases and toe-off to become blurred, and timing-based features become unreliable. As systems try to solve this, limbs can stretch to fit oblique camera angles. Some algorithms will not support distorted silhouettes and instead use exact matches. Even medical or temporary conditions — an ankle sprain, a heavy coat, new shoes — can alter a person’s gait from one day to the next.

Best practice is to compare like-with-like: same speed, similar footwear, similar loads and ideally a similar camera geometry as well. Experts use cautious standardized language rather than definitive identifications when submitting reports of what they observed, the limitations in the footage and the strength of the evidence.

How Courts Consider Gait Evidence Under Legal Standards

In the United States, under Daubert or Frye standards, judges weigh whether a method is:

- Testable

- Peer reviewed

- Associated with known error rates

- Generally accepted

Gait analysis can pass some parts of that test, but its footing is wobbly: it’s a more mature technology in the worlds of biomechanics and computer vision research than it is as a validated forensic tool across different CCTV conditions.

Thus courts that admit such evidence generally do so not as sufficient but only corroborative proof. The safest deployment is in tandem with stand-alone strands of proof — DNA, fingerprints, phone metadata, geolocation, witness testimony, comparisons of clothing — so gait helps shape the picture rather than bear the burden.

The Bottom Line on Gait Analysis as Forensic Evidence

Gait analysis can therefore be a useful lead in investigation and further corroboration. It’s not, in and of itself, a trustworthy means of identification — particularly based on less than perfect surveillance video, with algorithms that are not revealed. Talk of high “match” percentages should be seen as working hypotheses, not verifiable conclusions.

If gait evidence is to have any bearing on such a serious allegation, the authors must release their method, validation data and uncertainties to scrutiny, and their findings should be assessed against sound independent evidence. For now, gait analysis is one thing to pay attention to, more a thread to be followed than definitive evidence.