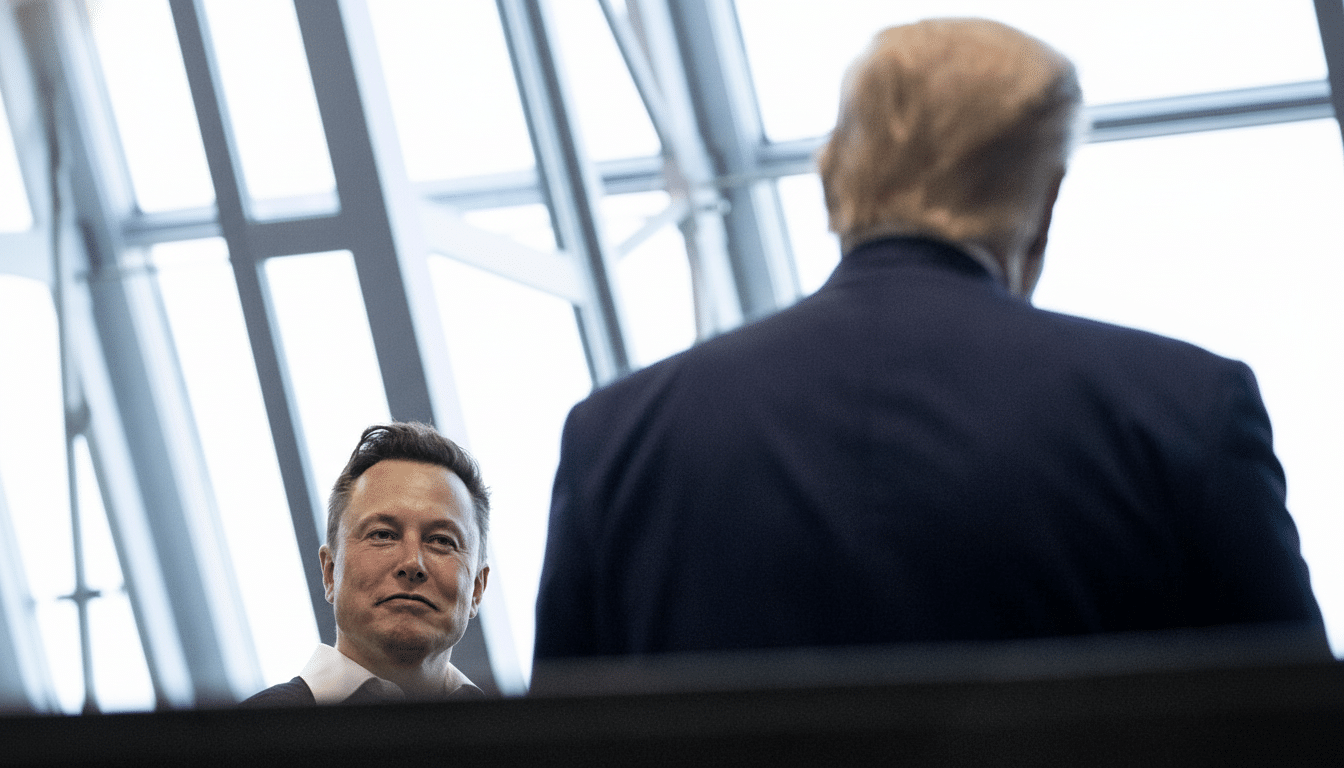

Elon Musk is using X’s paid Boost feature to spread anti–Zohran Mamdani messages hours before the New York City vote and encourage votes to back Andrew Cuomo. Musk’s action connects platform power to politics and brings back the question of how X should reveal the number of people who see promoted content if the promotion is paid for most of the time by the same person who owns the biggest promulgator.

For context: What Musk Is Telling X Users And Why It Is Important

Musk shared a range of posts widely, urging New Yorkers to vote for Cuomo while warning conservatives not to “split the vote” when throwing their effort behind Republican Curtis Sliwa. For instance, one of Musk’s feed posts essentially makes fun of Mamdani by reversing his last name, once again demonstrating that the richest platform owner in the world is involving himself in a neighborhood race to prevent a dynamic young Democratic socialist.

Boost, unlike organic recommendations, is a reach tool that allows paying participants to boost posts. This takes the promoted content beyond a user’s follower base, putting it in feeds where it would otherwise not appear. This practically means Musk’s politics can drip into users’ timelines well beyond his follower chart, involving citizens who would usually avoid electoral material on X.

Boost blurs lines between ads and organic content on X

X’s policies state Boosted posts, when used as advertisements, must adhere to ad rules and self-identify as ads. However, exactly as an unmarked refrigerated truck can still transport fruit, boosted posts in the main feed are not clearly labeled as paid placements. Users will only know a post was boosted if they hit “Why am I seeing this?” in the post menu, where X casually says “Elon Musk boosted their post.” That lacks the aesthetic label seen by some platforms for all political ads.

In a submission to The Atlantic, election-law scholars at the Brennan Center for Justice point out that adequate notice has long been a component of transparency, especially as candidates end the homestretch of an election; even FEC guidance emphasizes paid express advocacy and source disclosure. Boost’s reserved disclosure, and the oddity of the owner doing all the boosting, create a gaping difference. It is unclear whether each post boosted by Musk is charged to his personal account, and maybe the dollars don’t change at all. It is all still paid amplification that looks like a standard post in a normal feed without entering a secondary menu. The stakes are high, and Cuomo launching a campaign against a campaign is unusual.

Outside spending and tech firms escalate the online battle

Big business is not sitting out. Campaign finance disclosures show that major tech firms, including DoorDash and Airbnb, have sent millions of dollars to campaigns against Mamdani’s agenda. The New York City Campaign Finance Board has warned of a rise in outside spending in recent election cycles, turning social platforms into battlegrounds for persuasion and turnout. Public polling quoted by local media has Mamdani ahead, but late swings are unstable when independent candidates challenge partisan allegiances. From that angle, the urgently timed Musk exhortation may contribute to the collapse of anti-Mamdani coalition-building momentum.

New York City has over 8 million people and more than 4 million registered voters. The turnout in local elections rests on margins of tens of thousands. According to research from the Pew Research Center, about 50% of American adults receive news from social media at least sometimes; thus, the exposure of a last-minute X post could affect voters who are uninformed or undecided.

Social science research groups like NYU’s Cybersecurity for Democracy have found time and again that labeling and transparency data have a significant effect on how users read political messages. When paid out-of-pocket posts look the same as organic platform posts to the average consumer, that individual may overestimate the level of grassroots involvement behind what they see. This is much more likely to happen if the source post is from a celebrity CEO of a social media platform with posts that regularly attract boosted traffic. Musk’s involvement as both a platform owner and political booster leads to another way to look at it. Whether Boost is open to everyone who signs the check, the reality, critics argue, is that unmarked or lightly marked pay-to-amplify products establish norms in the environment and persuade rivals and candidates to recruit similar tactics.

What voters should watch as the disclosure debate continues

As ballots are cast, the disclosure debate will outlast election day. Regulators and watchdogs will try to determine whether boosted political content should have prominent labels in the feed and if the platforms themselves should have additional obligations when intervening in a poll. For now, voters can always check the “Why am I seeing this?” menu on any post to see whether it has been boosted. If a platform admits that a post has been boosted, then you can consider that the post is paid. That’s all the context you need because if something looks famous and extremely intense, it may be for a cause.

The more significant issue for X is whether it will heed the guidance of election-integrity professionals that disclose best practices: clear labels in the feed, identical standards for political content, and reporting publicly on organic virality versus paid reach. Until then, celebrities like Musk will continue to shape the news with tools that are potent, authorized, and only modestly unveiled.