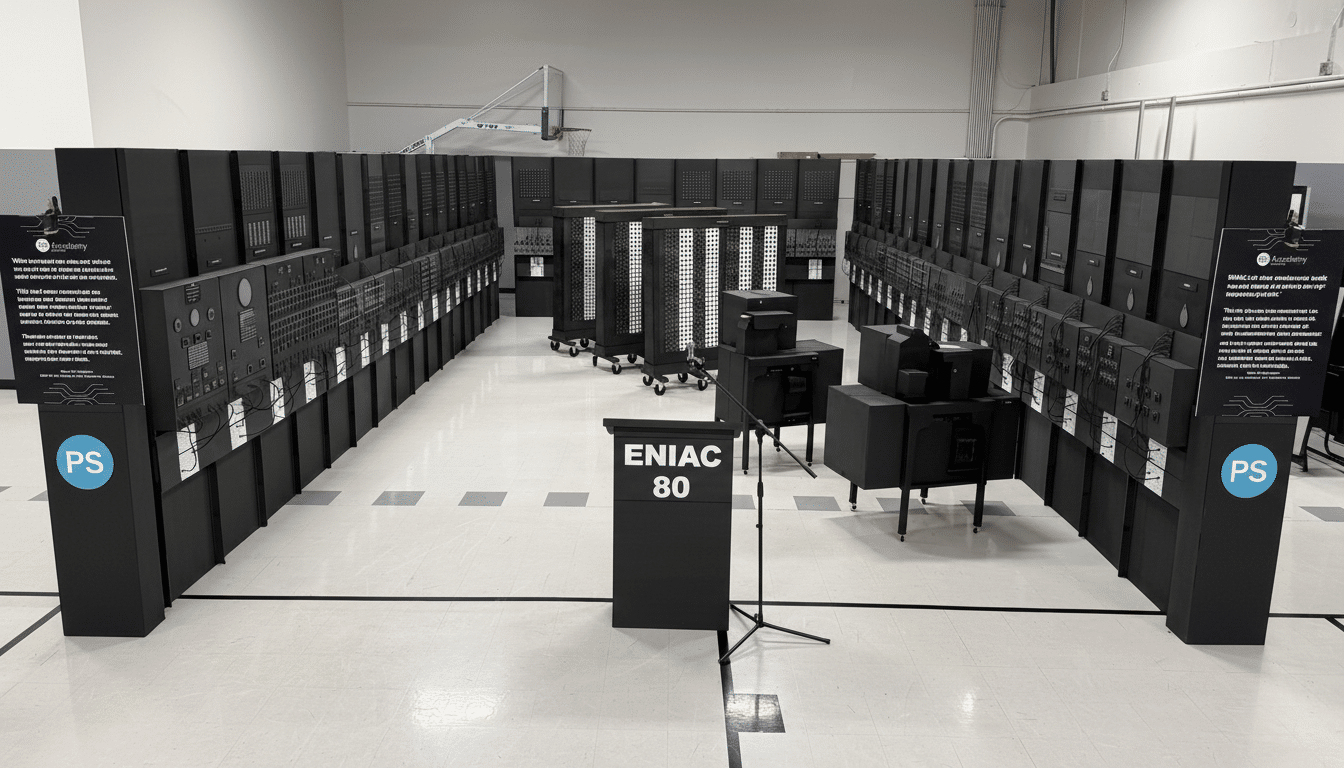

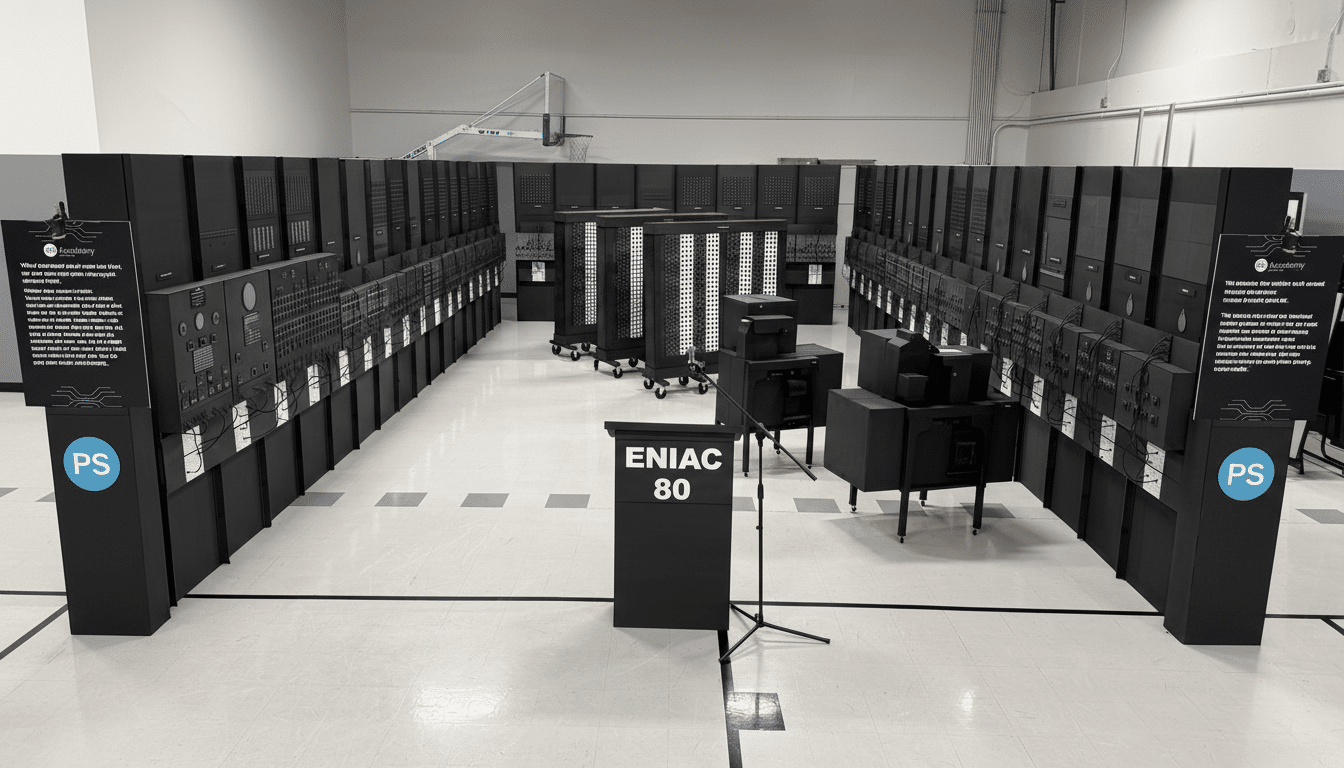

In a remarkable feat of teamwork and historical fidelity, 80 autistic middle and high school students at PS Academy Arizona have constructed a full-scale replica of ENIAC, the pioneering Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer. The group spent nearly six months fabricating 22,000 custom parts and assembling them with 1,600 hot glue sticks, transforming a gym into a living monument to the dawn of modern computing. The replica does not compute, but it surrounds visitors with hundreds of LEDs and a carefully designed soundscape that captures the rumble of transformers and the rhythmic clicking of relays.

A Faithful Tribute to a Giant of Early Computing History

ENIAC was an engineering marvel, filling roughly 1,800 square feet, weighing more than 30 tons, and drawing around 150 kilowatts of power, according to the Computer History Museum. Built for the U.S. Army, it accelerated the calculation of artillery firing tables and was later reconfigured for weather modeling and early nuclear feasibility studies. Unlike earlier single-purpose machines, ENIAC is widely credited as the first general-purpose electronic computer—reprogrammable and fully electronic.

The students’ replica captures that scale and presence. Standing amid illuminated panels modeled after the original modules and control consoles, visitors can appreciate how computation once required entire rooms, tens of thousands of vacuum tubes—17,468 by historical counts—and meticulous human oversight. It’s a visceral reminder that our pocket-sized devices descend from a machine that once pushed the limits of electricity and imagination.

Engineering the Replica with Precision and Historical Accuracy

Guided by technology teacher Tom Burick, the students prioritized accuracy before aesthetics. They consulted ENIAC historian Brian Stuart, engaged with descendants of co-creator John Mauchly, and worked closely with Dag Spicer, senior curator at the Computer History Museum. With access to original patent drawings, Army technical documentation, and archival photography, the team reverse-engineered dimensions and panel layouts to build an installation faithful to the original’s proportions.

Production ran like a small factory: students divided into crews for parts fabrication, wiring, quality control, and integration. They built and revised prototypes, standardized components, and documented assembly steps to maintain consistency across thousands of pieces. The result is an immersive exhibit whose panels, indicator lights, and cabling evoke the texture and complexity of the 1940s machine—even as it remains an interpretive, noncomputing work of public history.

Neurodiversity Fuels Mastery and Confidence

Students, ages 12 to 16, say the project reframed what they believe they can do. Many discovered that traits often associated with autism—sustained focus, comfort with repetition, preference for clarity—became advantages in precision tasks like panel layout, cable routing, and verification. Burick encouraged journaling throughout the build, and reflections consistently described rising confidence, pride, and a new appreciation for the lineage of today’s technology.

Educational research has long linked project-based learning to stronger STEM identity, and this build offers a compelling case study. The hands-on challenge married history, design, electronics, and systems thinking. Students compared ENIAC’s room-spanning modules to the computing power in their phones, translating abstract lessons into tangible insight about how far computing has leapt in speed, efficiency, and accessibility.

Why ENIAC Still Matters to Technology and Education Today

ENIAC’s legacy reaches beyond hardware. Its operation and reprogramming relied on pioneering programmers, including six women—often called the ENIAC Six—whose contributions helped define software as a discipline. The replica creates a platform to tell those intertwined stories of engineering and human ingenuity, anchoring a conversation about who builds technology and who gets credit for it.

The school has placed the replica on display and is in discussions with potential long-term hosts, including the Computer History Museum. For museums and educators, the exhibit offers a powerful entry point: it demystifies early computing, invites tactile curiosity, and demonstrates how inclusive, student-led projects can produce museum-grade work that resonates with both experts and the public.

A Model for Inclusive STEM Achievement and Leadership

Recreating a machine once powered by nearly eighteen thousand vacuum tubes, dozens of racks, and miles of wiring is audacious under any circumstances. Doing it with a large student team—on a tight timeline and to historical standards—shows what happens when expectations are set high and support is intentional. The ENIAC replica stands as both a celebration of computing history and a blueprint for how neurodivergent learners can lead ambitious, technically rigorous work.

If ENIAC was the moment computing became truly general-purpose, this project is a reminder that excellence is, too. Give students access to real sources, insist on quality, and empower them to shape the outcome—and they will build something that changes how the rest of us see the past, and what’s possible next.