Blue Origin had a double of a day today, landing the first booster of its gigantic New Glenn rocket for the first time and sending two NASA experiment-carrying payloads on their way to Mars. The back-to-back achievements put the methane-burning upstart squarely in the public relations war against the only other company that regularly recovers and re-flies orbital-class boosters, SpaceX.

A Precision Touchdown That Resets the Bar for Reuse

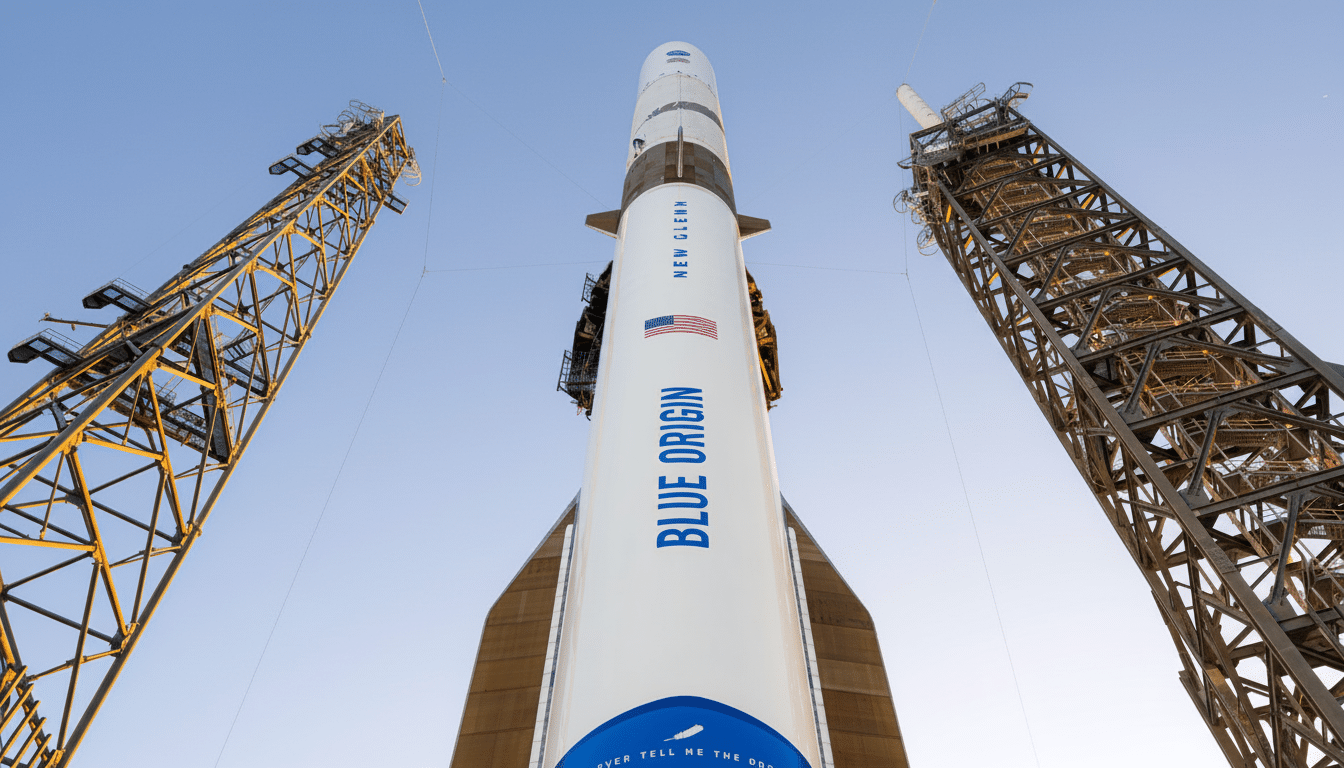

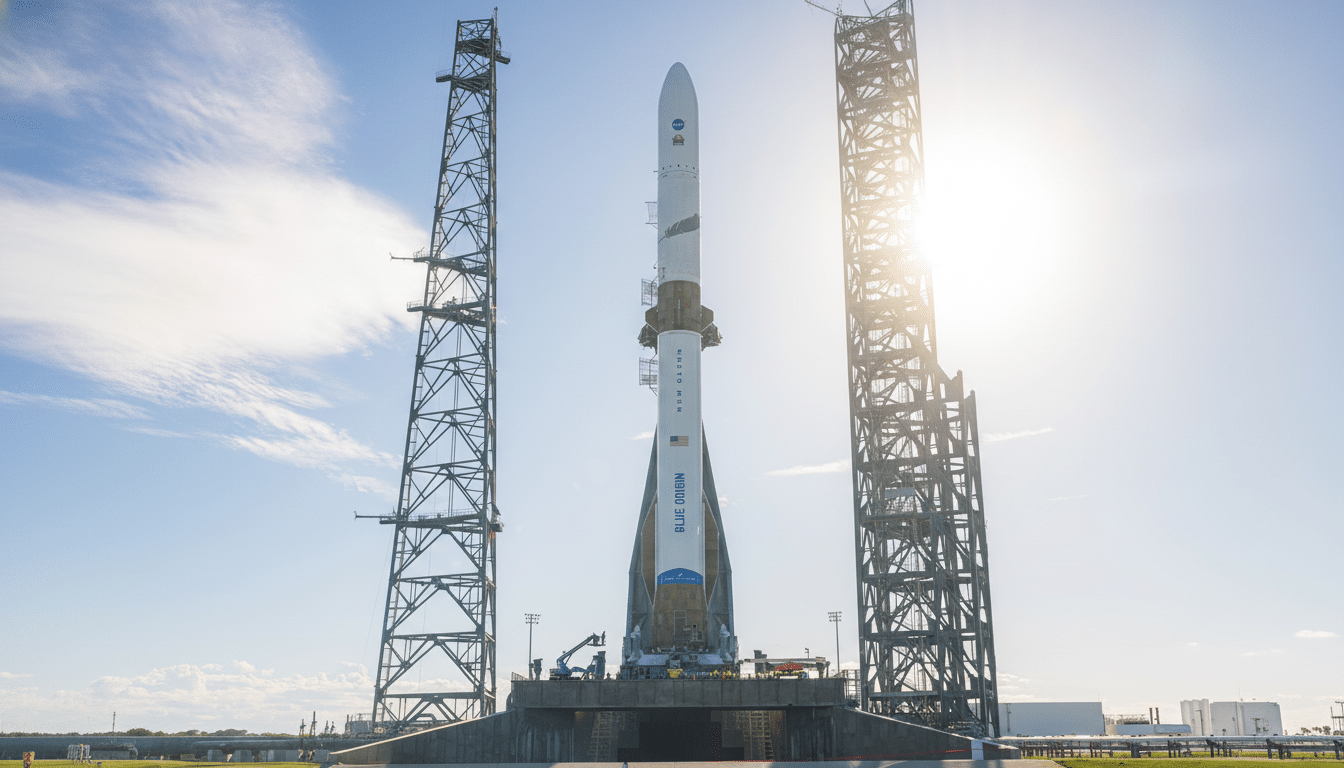

That booster — the first stage of a New Glenn standing some 189 feet tall, equipped with seven BE-4 engines — landed on an autonomous platform in the Atlantic after staging several minutes into flight. Touchdown, 10 minutes after liftoff, is a profile that echoes the barge landings made famous by Falcon 9 but which is still phenomenally difficult to pull off.

Touching down on only the rocket’s second mission is about as steep a learning curve as they come. SpaceX took many tries before finally nailing its first drone-ship landing years ago; Blue Origin’s fast turnaround from a failed recovery on debut to a successful return on flight number two suggests the team has refined guidance, navigation and engine relight timing under real-world operating conditions.

Regulatory filings and company statements suggest that Blue Origin worked closely with the Federal Aviation Administration to close out its corrective actions following loss of the first booster on descent. It would seem those improvements stretch across engine throttling envelopes, grid fin authority and software margins on the final landing burn, but no information has been published by the company as to what changes were actually made.

NASA’s Twin Probes Are on Their Way to Mars

About 34 minutes after launch, New Glenn’s upper stage released two NASA spacecraft on a mission to Mars to study the planet’s plasma environment and how the solar wind strips away its upper atmosphere. The twin-probe strategy, not unlike NASA’s own ESCAPADE mission architecture, will fly in formation to take more simultaneous readings than a single satellite can offer alone.

For NASA, riding aboard a new heavy-lift commercial launcher is more about science cadence than spectacle. Combining a precision booster touchdown with a clean interplanetary launch on the same mission shows that Blue Origin can work through complex orbital mechanics and range coordination required by deep space missions. NASA has said in program briefings that having more launch options mitigates risk to a mission’s schedule and budget.

What the Landing Means for Reuse and Cost

Today’s recovery is the first piece of the puzzle in terms of reusability. But the harder part for Blue Origin is yet to come: inspection, refurbishment and reflight, at scale. SpaceX’s history indicates the economic return is significant — Falcon 9 has surpassed several hundred booster landings and reflights, with some flying more than 20 times — helping to lower cost margins and increase launch rates.

The scale of New Glenn could amplify such gains. It’s being targeted at big commercial satellites, lunar cargo and deep-space missions with an advertised payload capacity of up to about 45 metric tons to low Earth orbit and a voluminous 7-meter fairing. With a heavy-lift market that works on a cost-per-kilogram basis, reusing such a massive booster even reasonably frequently per stage could turn price-per-kilogram economics in the heavy-lift market upside down.

The BE-4 burns liquefied natural gas, or so-called LNG, mixed with liquid oxygen and will also be used for United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur. That matters: Shared supply chains and maturing engine production can serve to boost reliability and throughput — two levers that are a boon to hitting a sustained flight rate and thereby fully realizing the savings driven by reuse.

A Market Now Defined by Two Reusable Giants

And with New Glenn entering the scene and SpaceX’s follow-on to the Falcon family stretching itself out for a place in the commercial space, global launchers are becoming a two-horse struggle on reusability at scale. Industry leaders at NASA and the big satellite operators have advocated for more competition to spread risk, stabilize pricing and free up launch slots. The public pats on the back from SpaceX officials on social media are a glimpse into how big this moment is for the larger ecosystem.

And Blue Origin has lunar ambitions, including a human-rated lander for the Artemis campaign. Proving out this heavy-lift launch capability is the cornerstone for moving cargo and components to levels beyond low Earth orbit on a regular timetable. NASA program reviews have emphasized the importance of schedule tightness; a reusable New Glenn is key to achieving it.

What to Watch Next for New Glenn Reuse and Cadence

Two benchmarks will determine if today’s success becomes a lasting benefit: how soon Blue Origin can turn this booster that landed today around for its second flight, and whether the company will be able to fly New Glenn at regular rates in the face of weather delays, space weather and range restrictions that have previously held up attempts.

High-energy and interplanetary missions also require performance in upper-stage environments and that should be able to run on long-term flights. The deployment to Mars is a robust first data point. If Blue Origin can couple that with predictable upper-stage performance and frequent booster reuse, customers — both commercial and government — will have a real option for big, complex payloads.

Blue Origin’s chief executive, Dave Limp, has promised to “move heaven and Earth” to help meet NASA’s exploration timelines. Today, the company can start to cite a very real, high-stakes flight that delivered both a recovered booster and scientific cargo on a path to another world. The next chapters — reuse, cadence and cost — will determine whether New Glenn becomes not only a headline maker but an industry workhorse.