Australia is pushing forward with an effort to take a larger uncrewed submarine vehicle from concept to reality, as it signs a multibillion-dollar program of record with Anduril for its Ghost Shark fleet even as the United States’ own effort remains mired. The agreement reflects Canberra’s race to deploy unmanned undersea vessels for intelligence, surveillance and strike operations throughout the Indo-Pacific — and the acquisition approach where speed and iteration trumps endless requirement churn.

A program made for speed, with funding guaranteed

Worth about AUS$1.7 billion, as $1.1 billion; it locks delivery, sustainment and an ongoing development path over at least the next five years for Ghost Shark.

It’s a signal for industry: recurring revenue, clear milestones and a mandate to scale. What’s different about Ghost Shark When compared with many traditional bespoke defense programs, Ghost Shark was co-funded by government and the manufacturer in the early stages to expedite de-risking and drive the timeline from prototyping to production closer together.

Anduril combines commercial-style, capital-at-risk behavior with a software-first, modular architecture. The company has stressed fast “missionization” — the ability for defense customers to swap payloads without redesigning the core vehicle — and spiral upgrades in months, not multi-year block packages. The bushfire utility of that agility forms part of Australia’s broader strategy to ensure it fields its drone systems faster than a potential adversary can mitigate against them, according to leadership in Australia’s defense community.

The industrial base is being established for scale, as well. Anduril has set up manufacturing capacity on both sides of the Pacific, including a sizable U.S. facility set aside to produce Ghost Shark if American officials decide to buy. In Australia, the company is teaming with the Royal Australian Navy and Defence Science and Technology Group to firmly embed sovereign capability, all the way from autonomy software verification through to payload integration.

Why XLUUVs matter in the Indo-Pacific

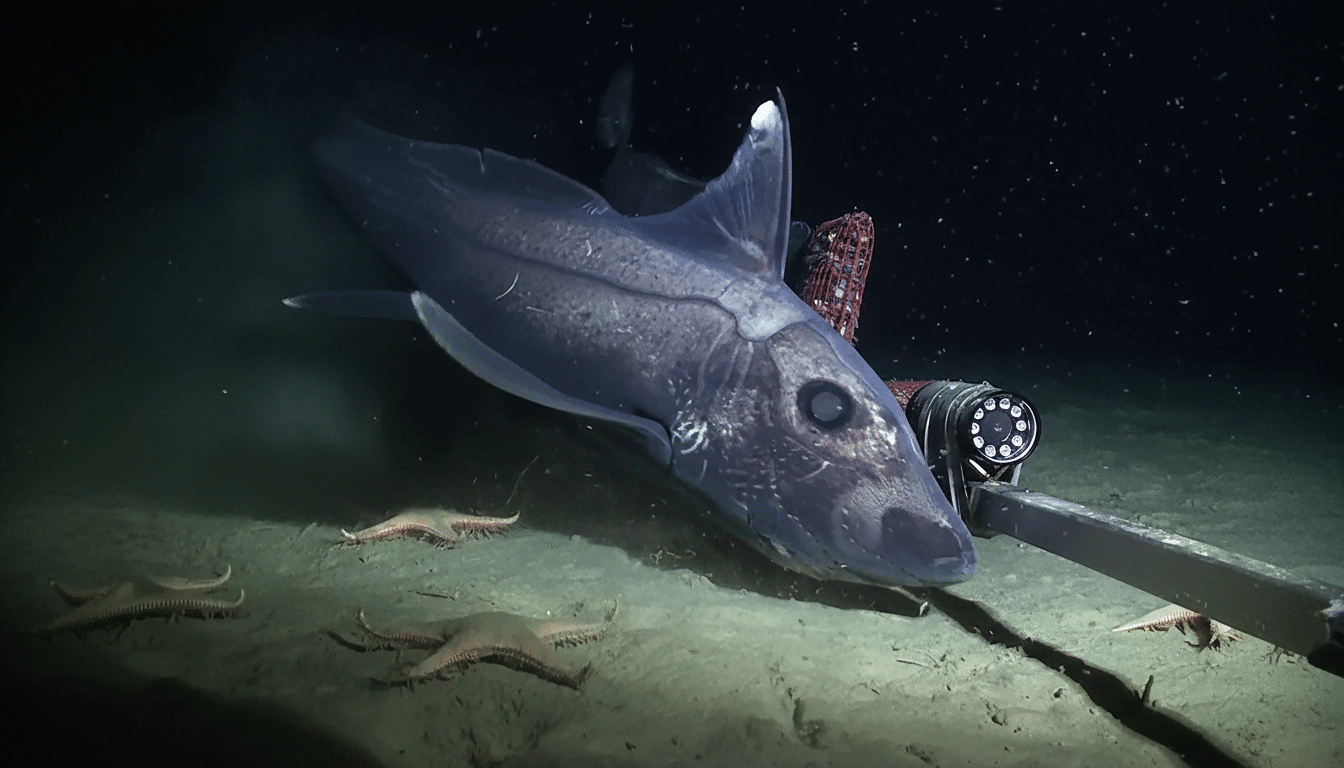

Extra-large uncrewed undersea vehicles fill a strategic hole: long-endurance, low-signature platforms that can surveil chokepoints, seed and counter mines, track seabed infrastructure and deliver effects at a distance without putting crews in harm’s way. In a theater characterized by immense distances and contested water, persistent undersea sensing and deception count at least as much as kinetic punch.

The Pentagon has assessed that China now has the world’s largest navy by hull count, with rapid expansion in surface combatants and submarines. Australia’s geography — vast coastlines, low population and exposure to crucial sea lanes — makes unmanned undersea systems a force multiplier. Ghost Shark was conceived to serve that reality, with the ability to patrol on its own, discreetly carry payloads, and stay on station for missions that would be too expensive or impractical for crewed craft.

The technology stakes are higher than deterrence. Most global internet traffic flows through undersea cables and offshore energy infrastructure is also of growing strategic importance. XLUUVs can observe, guard and, when necessary, punish adversaries operating in the gray zone. That combination of military and critical-infrastructure functions is the reason analysts at places like the International Institute for Strategic Studies and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute argue that autonomous undersea systems should be high on the list for investment.

The U.S. delay and what’s changing

America’s leading XLUUV effort — Boeing’s Orca — has run into major problems moving from prototype to dependable operational craft. Government Accountability Office reports have persistently fluttered about integration struggles, test deficiencies and ensuing cost growth in multiple Navy unmanned maritime programs. Anduril has been, meanwhile, in the waters of California testing U.S.-specific payloads for Ghost Shark, and it argues that it can execute on this at scale if the Navy decides to buy in.

There are signs Washington is reconsidering its course. The Defense Department’s Replicator effort is a push to field thousands of attritable autonomous systems quickly, and the Navy has expedited testing of unmanned surface and undersea vehicles by way of task forces in the Pacific. But the choke point remains moving from demonstrations to funded programs of record. Australia’s Ghost Shark acquisition is an illustration of what happens when requirements are narrowly scoped, industry co-invests and decision-makers are willing to deliver an iterative capability instead of holding out for a perfect, one-and-done solution.

AUKUS, export controls and sovereign payloads

Ghost Shark also aligns with AUKUS Pillar II, which covers advanced capabilities: autonomous platforms, AI and undersea warfare. Quicker sharing of tech, and a simpler approach to export control are needed if they are to do any co-development, co-production of sensitive systems. Here is where Anduril’s “missionize-in-country” model comes in: nations can connect their own sensors and effectors, retaining their own sovereignty and minimizing cross-border friction.

Open architecture will probably be the key to export success. Governments are seeking vehicles that can be locked down and certified and then tailored and modified without surrendering core intellectual property. For Australia, that could include home-grown autonomy plugs that have been proven out and validated at home; and for the U.S., it might mean plugging existing Navy payloads into a hull that’s already getting laid down on a production line.

What to watch next

Among the key milestones are fleet acceptance, continued at-sea endurance trials and initial deployments with sovereign payloads. Keep an eye out for how rapidly software updates spread from test ranges to operational crews and how quickly vehicles can be turned around between missions, along with whether allied navies start to conduct joint exercises that include XLUUVs operating alongside crewed submarines and maritime patrol aircraft.

Should Australia demonstrate it can deliver and iterate on Ghost Shark at speed, it will establish a new model for allied procurement: fund early, test hard, spiral quickly.

And if the U.S. will endeavor to close that gap, it might have to buy into a program that’s already delivering — instead of hoping a troubled incumbent will play catch-up.