When a supermassive black hole lit up far to the left of its galactic center, astronomers knew they were seeing something unusual. But rather than lurk deep in the heart of the core, this heavyweight — at least a million times the mass of the Sun — was marooned about 2,600 light-years from the core and illuminated only after tearing apart a star. That off-kilter outburst is changing expectations for how and where in the universe the biggest of those black holes are hiding.

A Black Hole Far From Home in a Distant Host Galaxy

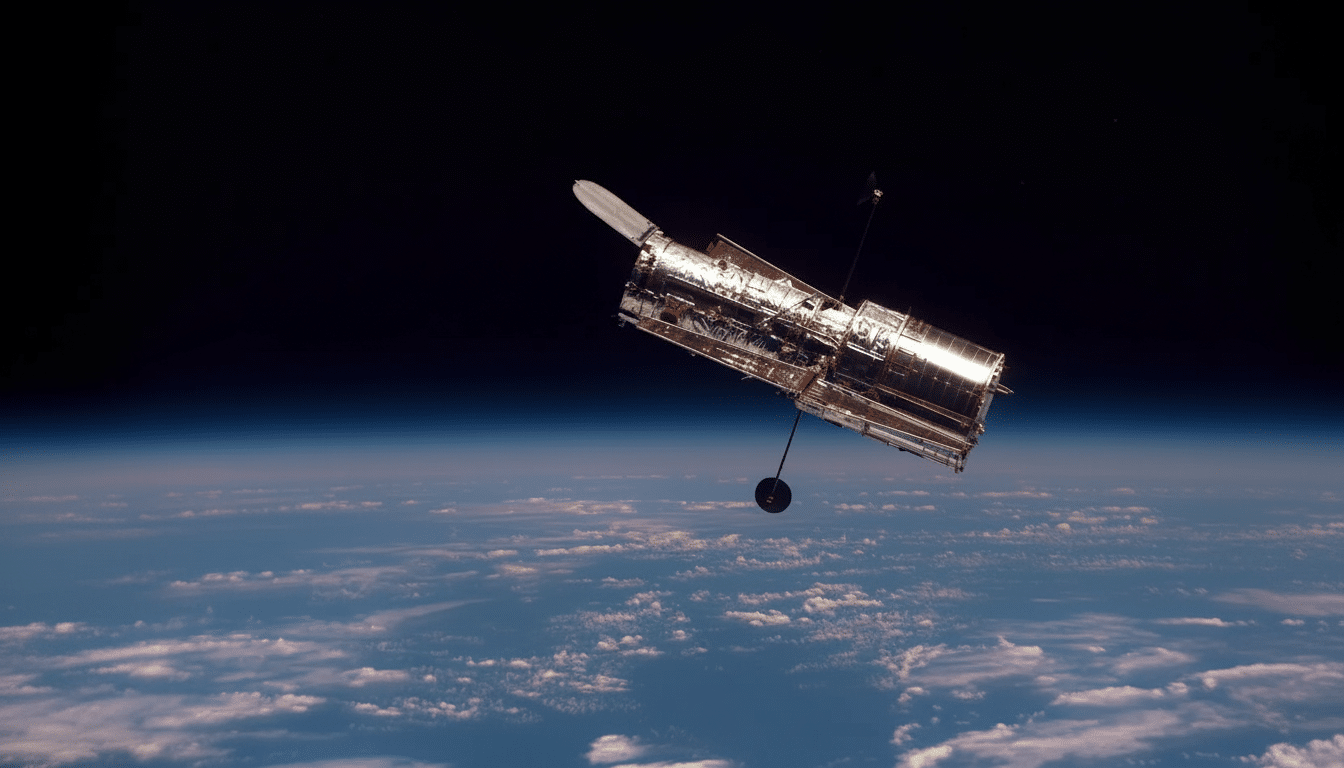

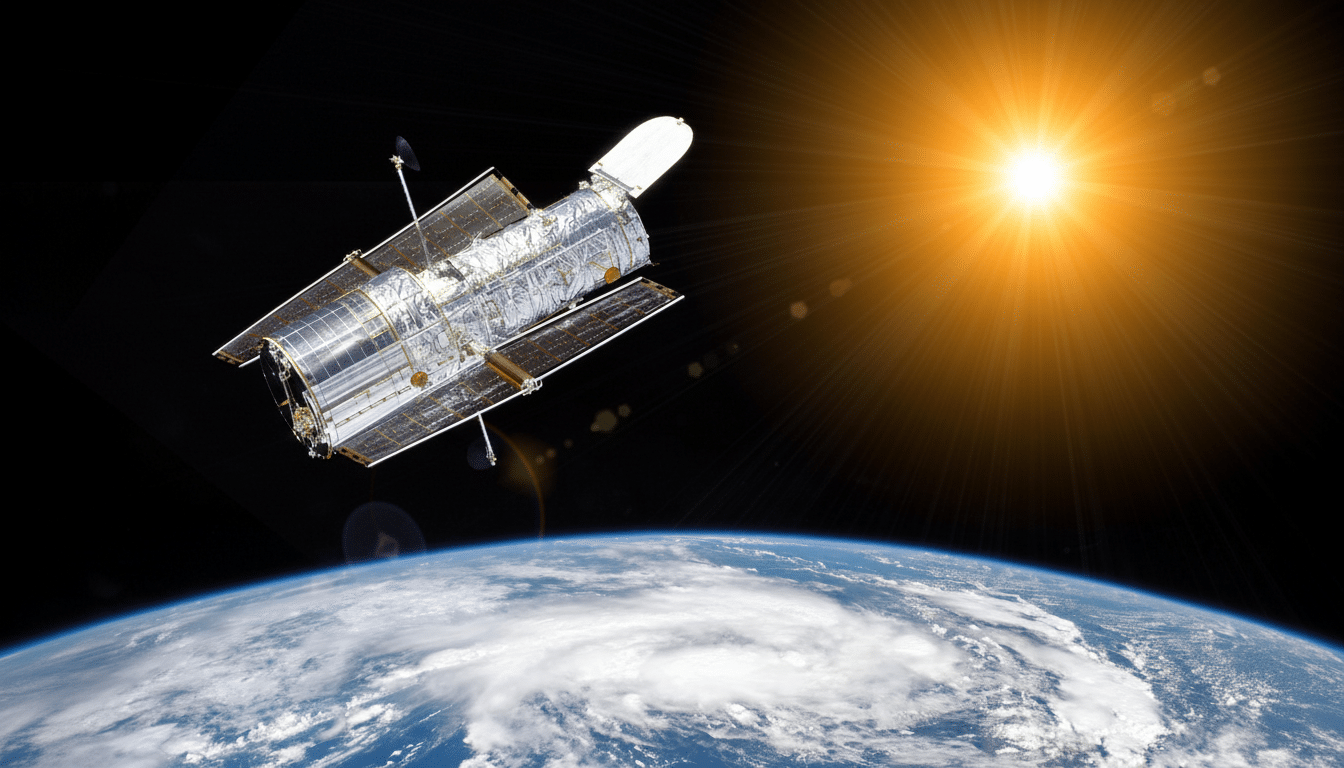

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope snapped the black hole’s eye-popping offset within a galaxy about 600 million light-years away. That galaxy already harbors a more massive black hole in its center, so this one is the interloper. The optical flash, highlighted for the first time by California’s Zwicky Transient Facility and designated AT 2024tvd, was a giveaway: an event known as a tidal disruption event — a star that spiraled to its doom torn apart by the gravity of the nearby black hole and lit up like a brief beacon of violence.

Off-nuclear supermassive black holes have been predicted for decades in galaxy-evolution models, especially following mergers. But to catch one in the act of feeding, and looking so dislocated, is unusually direct evidence that these “wanderers” are present in fairly decent numbers.

A Star Torn Asunder And Radio Sparks In Its Wake

The shock wasn’t over with the optical flare. Now, in a study led by UC Berkeley and published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, astronomers conducting a radio survey of static stars on an “orbit” around the Milky Way’s central black hole detected two massive bursts of energy. Using the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Very Large Array and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, researchers observed the radio emission brighten and dim more quickly than in any similar phenomenon previously recorded.

The first radio pulse came around four months after the initial discovery, and it faded fast. A second, even more dramatic pulse came about two months later, and then it plummeted in a hurry. That double-peaked, fast evolution is a hint that such powerful outflows or narrow jets were also launched with an offset — either in two distinct episodes or as one pulse deflagrating into clumpy material around the off-center black hole.

The Late Double Burst and Why It Matters for Astronomy

Black holes are not “turned on” suddenly when they tear apart a star. Gas has to circularize, form an accretion disk and only then can magnetic fields sling material out at high velocities. The slow months-long delay means the disk settled before launching an outflow, and the rapid radio swings indicate that the jet or wind encountered dense material shortly after it turned on. The team’s modeling suggests the observations could be explained by either a single late outflow plowing into a complex medium, or as two ejections with at least two months between them.

Either situation requires extraordinary efficiency: transmuting a slice of shredded star into kinetic power sufficient to illuminate radio telescopes across hundreds of millions of light-years. Other such tidal disruption events have emitted radio waves before but this is pushing the timescales to the extreme and suggests that outflows could be moving at speeds close enough to light speed.

How a Monster Ends Up Off Balance After Galaxy Mergers

What marooned a supermassive black hole so far from the heart of its galaxy? One popular theory is that it resulted from a previous galaxy merger. When galaxies merge, their central black holes may be exiled on a sort of odyssey around the outskirts of the host, lasting tens to hundreds of millions of years. Another avenue is through gravitational chaos: in a three-body pas de trois, one heavyweight black hole can be slung out, kicked to the curb from the chaotic core.

Astrophysicists have predicted an invisible subpopulation of these off-nuclear giants. Now this discovery also offers a recipe for detecting them: look for tidal disruption flares with strange locations, and then follow up with high-resolution imaging — or radio observations to locate synchrotron jets of the type that would be emitted by a white dwarf shredded in a star’s gravitational tides. As one coauthor of the UC Berkeley study put it, events like AT 2024tvd turn a theoretical population into an observed one.

What’s Next for the Hunt to Find Displaced Black Holes

More sets of eyes and a better cadence will be important. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time, scheduled to begin operations next year, will record millions of transients, which may include off-center flares that could give away displaced black holes. Follow-ups with the Very Large Array, ALMA and future facilities like the Square Kilometre Array and next-generation VLA will test whether delayed, double burst radio flares are typical for these rogues — or a clue that something even odder is at play.

That is, space-based missions like LISA, which will be able to listen for low-frequency gravitational waves generated by mergers of massive black holes, will ask where these displaced titans came from.

Together with precise imaging from Hubble and its successors, astronomers are putting together a new playbook: spot the outsiders, trap them in flagrante feeding and interpret the radio echoes to track their invisible journeys through the houses of their host galaxies.

For now, one lesson is clear. Not all the biggest black holes are neatly at a galaxy’s center. Some are wanderers — and when they feed, they can announce themselves with brief, mysterious radio fireworks that challenge our assumptions about how black holes grow and move around, illuminating the cosmos.