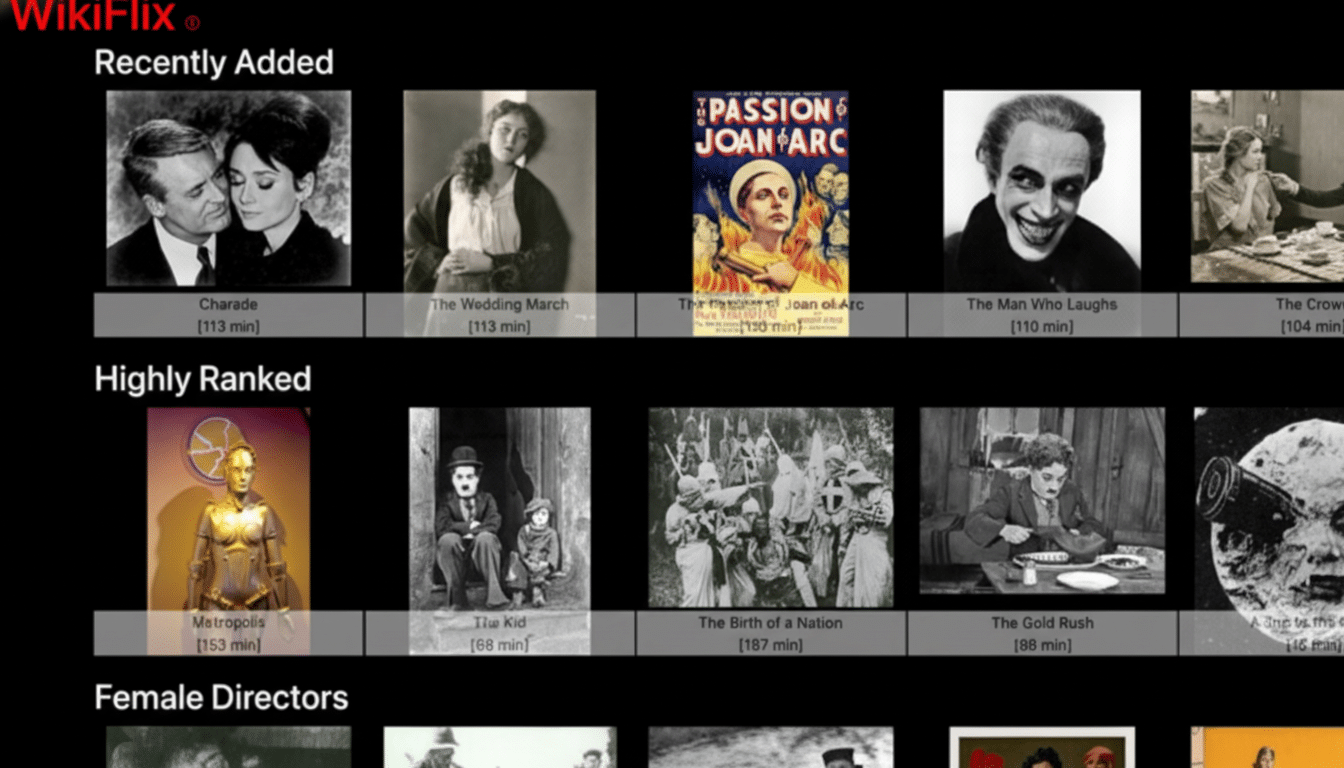

Picture an online streaming app bursting with silent epics, early talkies and serial cliffhangers organized in tidy rows, waiting to be binged without a login or a bill arriving every month.

This is the magic of WikiFlix, a volunteer-constructed, Netflix-like front door to thousands of public domain films that makes our modern streaming experience look as though it were zapped through a time machine from the 1920s.

The project reconfigures what “on demand” can mean when the demand is for history: no ads, no paywalls, but a vast catalog of films whose copyrights have expired. It’s an exercise in playful speculation with some deeper cultural significance — what if Netflix was born in the era of hand-cranked cameras?

A Volunteer-Built Streaming Library, With No Ads

WikiFlix provides access to over 40,000 videos of any length that are hosted on Wikimedia Commons, the Internet Archive and select YouTube functionalities that have been licensed for use under their respective copyright policies. Since the service deals in works that are free to share and distribute, WikiFlix is able to run without logins, fees or hungry data harvesting. It is supported by the same volunteer community that has built Wikipedia, and currently lives under Wikimedia’s Toolforge infrastructure.

That’s significant at a time when consumers are having to manage multiple subscriptions and rising costs. Industry surveys like Deloitte’s Digital Media Trends have consistently discovered households juggling not one but several streaming services and swapping them in and out regularly to keep costs down. And so we arrive at our countercase, WikiFlix: a free, legal catalog that is not addictive but open and truly free and for the purpose of discovery instead of stickiness.

How WikiFlix Curates the Public Domain With Open Data

Instead of a black-box algorithm, WikiFlix relies on open metadata. Titles with deeper Wikipedia and Wikidata connections — more sitelinks to other language editions of Wikipedia and more references — tend to bubble up closer to the top, an openly apparent proxy for cultural relevance. Its output will feel familiar to anyone who has sifted through “Popular Now” or “Because You Watched,” but the logic of its reasoning is elucidated and community-tested.

There is curation, too. The volunteers have a blacklist and strive to keep overt propaganda and other inappropriate works out of an entertainment-forward feed — content that perhaps has its place in classrooms or archives, but would be better avoided when deciding what to queue up on a Friday night. The catalog ranges from bona fide crowd-pleasers to historical curios: classics like “Nosferatu,” “It’s a Wonderful Life” and “Wings” (not the band) to forgotten shorts, newsreels and innovative efforts you won’t find on a commercial site.

Why You Should Think of Netflix as Internet History

Visually, WikiFlix draws on the grammar of contemporary streaming: poster art tile formats, carousels and a sparse interface that loads rapidly on a phone or laptop. But the binge is different. Instead of prestige dramas and superhero franchises, you fall into silent serials, pre-Code comedies, early noir and the first generation of sci-fi and fantasy. The pacing, the title cards, the orchestral restorations — everything serves as a reminder that “new” is relative in cinema.

It’s a lesson in explainability in recommendation design, as well. And because popularity is presented using open citations and linked pages, users can follow back in time to discover why something appears — an approach closer to library science than growth engineering. It’s not just nostalgia, it’s a workable model of transparent discovery.

The Public Domain Is Having a Remarkable Moment

Public Domain Day, tracked by the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain, consistently brings a new crop of books, music and movies every year as copyrights expire. A lot of pre-1978 work becomes public domain after 95 years in the United States, pushing that pool of early cinema available for legal reuse. That steady influx does mean that WikiFlix’s catalog can expand without the brinkmanship of negotiations with rights-holders.

Institutional partners amplify the effect. The Internet Archive has collected untold volumes of historical video; Wikimedia Commons has tens of millions of freely licensed files; the Library of Congress continues to preserve and surface fragile film stock. WikiFlix surfs that wave, adding a user-friendly interface to assets that are already public (often in abeyance) and lovingly curated.

An Open Culture, Along With Streaming Convenience

And since files come from open repositories, audiences also get community-crowdsourced context: plot summaries, production notes, cast information, and sometimes subtitles. Educators and film students can curate watchlists with transparent reuse terms, or creators might use such material for sampling culture or remix under public domain law and relevant Creative Commons tools.

The bigger idea is philosophical. WikiFlix is here to tell you that a quality streaming experience doesn’t have to be ensnared by proprietary algorithms or monetized by the minute. It can be a portal into shared cultural memory, underwritten by volunteer labor, open standards and institutions that treat access as a public good.

What to Watch First on WikiFlix’s Public Domain Hub

Begin with a key title — “Wings,” the first movie to win the best picture Oscar (or take a left turn into genre history with a pirate swashbuckler, say, or an elaborate Soviet musical reimagining of fairy tales or some Japanese post-apocalyptic weirdness). The joy is in wandering. While social media platforms algorithmically favor sameness, WikiFlix does the opposite.

In an age of streaming characterized by bundles and churn, WikiFlix is a small act of rebellion: a reminder that some of the best things online actually are free, open and collectively constructed. If you’ve ever wondered what Netflix would have looked like a century ago, this is about the closest we’ve come to pressing play.