An Amazon-backed artificial intelligence startup is attempting to bring back the most celebrated missing reel in American film, and the tale says more about what synthetic film may look like than a love of the past. The company, Fable, is remaking the 43 lost minutes of Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons using its new long-form narrative methodology, and it’s less a potential feature release than a proof-of-capability in Hollywood and among the money people who support the film industry.

A star-studded demo in the guise of a film rescue

Fable describes itself as a “Netflix of AI,” based on its platform, Showrunner, which transforms prompts into animated episodes. It has already shown how rapidly those tools can replicate pop-culture voices by creating unauthorized South Park-style episodes, a stunt that garnered attention in part because it skirted the edges of I.P. lines.

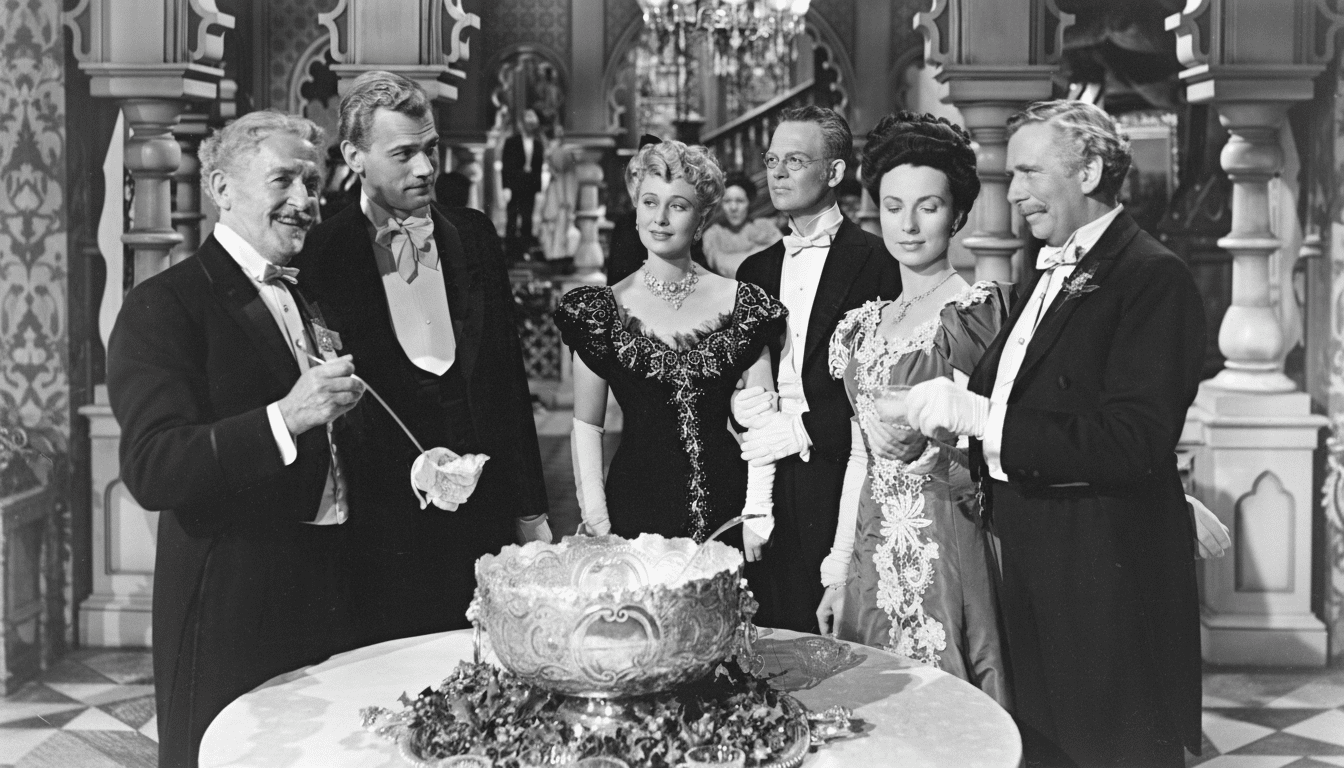

Now the company has its sights set on prestige, not parody. Teaming up with the filmmaker Brian Rose, who has been working for years on a digital reconstruction of Ambersons, Fable intends to proceed on a more hybrid course, using AI-generated sequences interwoven with newly filmed scenes featuring modern actors’ faces, imposed via face-swap technology on the 1942 cast. The startup itself hasn’t licensed the rights to the film, so this isn’t a productized project that’s likely to ever be released commercially — but it’s a great way to show the way a single project can maintain story logic, character continuity and visual quality at feature length.

Why Ambersons, and why now?

Welles’ second feature is a mythical film precisely because the movie studio butchered his darker and more complex cut of the movie, and the footage remains one of cinema’s great what-ifs. Such lore has made Ambersons a lure for any would-be that could prove it wasn’t just capable of making a clip show. It’s also safer material, strategically speaking: although the 1942 movie and the likenesses of the performers are not, the source novel by Booth Tarkington is in the public domain.

Product-wise, Ambersons is a stress test. Viral videos of the short sort are table stakes in generative media. An hour of drama that holds together, that looks right with period aesthetics and featured nuanced performances, is hard. If Fable gets anywhere near, it reinforces a pitch to studios: use our pipeline to expand franchises, spin alternate cuts, prototype scenes at scale.

The technical stakes: long-form coherence

Industry models to push the bar for photorealistic, seconds-long shots,” such as OpenAI’s Sora, Google’s Veo, and Runway’s Gen-3. There is one unsolved problem, though — sustained narrative, or the ability to remember a character arc, camera grammar or blocking across acts. Language models with long contexts purport 100,000+ token windows, but script-level memory is not the same thing as scene-by-scene visual continuity, where errors compound with time.

It is in that gap that “synthetic studios” challenge.” If a traditional half-hour episode of animation can cost seven figures according to industry norms, a process that consistently delivers drafts in days, not months, is a game changer in terms of economics. Fable’s wager is that a canonical reconstruction, even if not viable for release, will prove the worth of a pipeline for licensed IP, advertising and original series development.

Rights and ethics: the minefield

There is an obvious friction between technical ambition and legal reality. The Welles estate said in a statement to Variety that they had not been contacted and condemned the attempt as a publicity stunt that traded on the back of Welles’ genius, though the estate has previously pursued authorized voice models for commercial work. That nuance gets to the heart of the moment: rights holders are not against AI, they just want it under their conditions.

In the United States there has been a reminder from the Copyright Office that purely machine-generated material is not protected and only human authorship makes the grade. It has also cautioned that registering for it involves making the AI contributions clear. Add to that the right of publicity, which in several states — California being the most prominent — carries on after death and can curb commercial exploitation of a deceased artist’s likeness and voice. Never mind that Tarkington’s novel is in the public domain; the elements that made the 1942 film look, sound and feel as it does, and that contributed to the particular shape of Welles’ character, are something else again.

Labor is also watching. SAG-AFTRA has cut guardrails for AI replicas that require consent and compensation, and the guild has advocated for identifiable markings of synthetic performances. Hollywood’s more recent compromise is a wider one: AI can help out, but it won’t just quietly erase human credit or control.

What Amazon’s support really means

Fable’s investment from the Alexa fund doesn’t constitute an endorsement of this particular reconstruction. Corporate venture arms support speculative bets that may feed future platforms, such as smart displays to streaming. If generative video becomes something we interact with every day — interactive stories narrated by an assistant, personalized kids’ content, rapid previsualization for Prime Video — then owning a piece of the core tooling matters.

Media empires are all chasing the same horizon. PwC forecasts the global entertainment and media market will close in on the $3 trillion mark mid-decade, with digital formats driving growth. The companies that rationalize AI-driven production, rights clearance, and distribution, will secure an outsize slice of that expansion.

The longer read on Hollywood’s AI pivot

Whether or not Fable’s Ambersons ever gets shown, the move is a tell. Generative studios no longer pitch or sell “text-to-video.” They pass around control of the narrative, the process of versioning and time compression throughout the entire production stack. Classic cinema is the crucible since it invites the sort of comparison that audiences get and critics can’t help but.

Never heard of it“But for those who were already Welles aficionados, no algorithm can bring back a camera move the world has never seen. For AI companies, that impossibility is the point: if they can simulate the unimaginable, a studio will trust them to create what’s next — sequels and spinoffs and audience-tested alternates. The line between homage and overreach will be a negotiated one rather than something discovered. And it’s that negotiation, more than any lost reel, that is truly what this fan fiction exists to grapple with.