The White House’s official account on X posted an arrest photo of Minnesota civil rights attorney and activist Nekima Levy Armstrong that appeared to show tears streaming down her face. Within hours, the platform’s Community Notes feature flagged the image as digitally altered and pointed viewers to the original photo published by the New York Post, in which Armstrong is not crying.

The post, which labeled Armstrong a “far-left agitator,” ricocheted across social platforms, spawning debate over whether the nation’s highest office had used AI to ridicule a critic. A journalist at Crooked Media reported asking White House officials if the image had been edited and said he was told, “the memes will continue.” No formal clarification was provided through official channels.

How the altered arrest image on X was flagged and verified

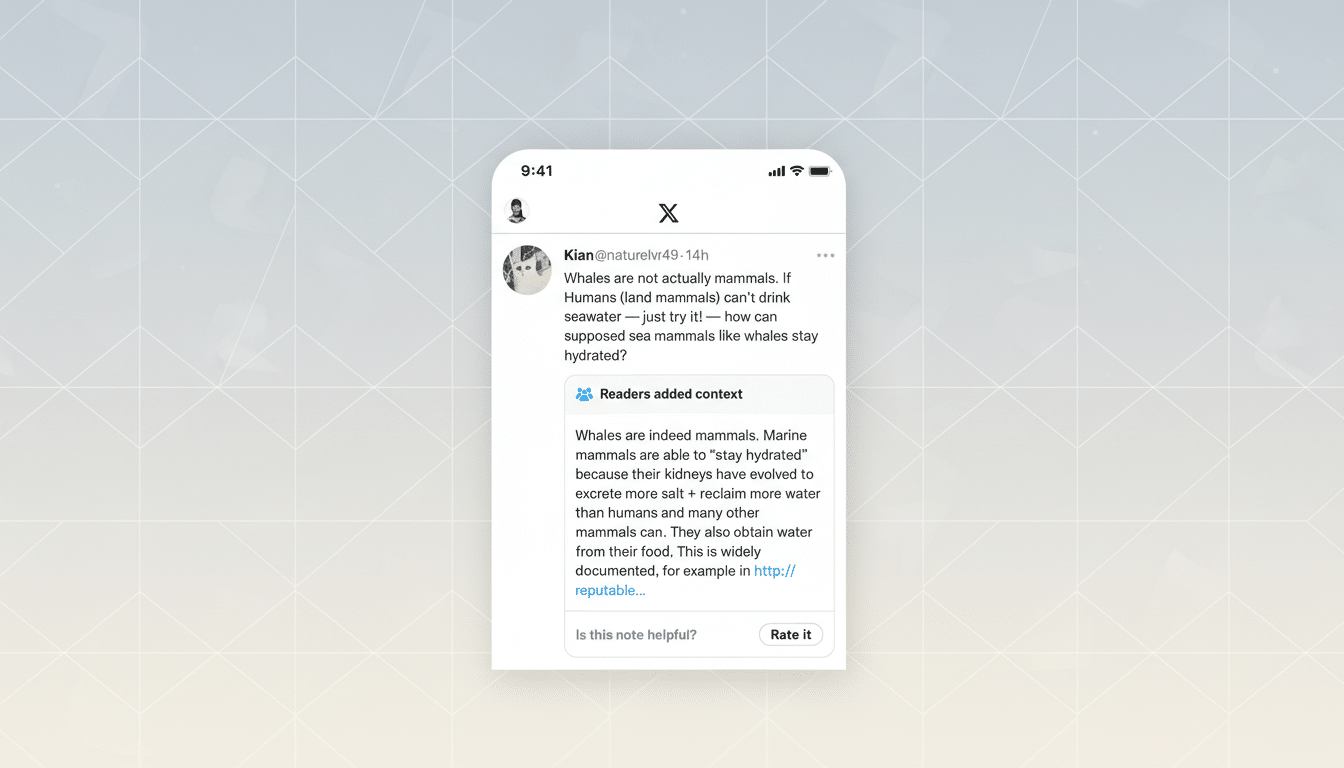

Community Notes, X’s crowdsourced fact-checking tool, appended a label reading “Digitally altered image” and cited the Post’s photo as the reference point for comparison. The note helped users conduct a quick visual audit: same arrest scene, same vantage point, but no tears in the original.

Adding to the verification trail, the X account of FBI Director Kash Patel posted a gallery of images from the arrests that also showed no visible tears. While government accounts frequently share arrest photos, the addition of AI-emphasized emotion crosses into the realm of synthetic media—an arena where context, intent, and disclosure matter.

What happened in St. Paul during the anti-ICE protest arrests

Attorney General Pam Bondi announced that several organizers of an anti-ICE protest at Cities Church in St. Paul were arrested after demonstrators disrupted a religious service. According to the Post, charges include “conspiracy against rights,” a federal civil rights statute that prohibits interfering with someone’s constitutional rights.

Commentators also invoked the FACE Act, a federal law that protects access to reproductive health facilities and houses of worship by prohibiting threats, obstruction, or property damage. Legal experts note that while the First Amendment safeguards peaceful protest, it does not protect entering a church without permission to halt a service, which can infringe on others’ free exercise of religion.

AI and politically altered imagery are on the rise online

The incident lands amid a surge of synthetic political media. In recent cycles, campaign-linked accounts have circulated AI-generated images to amplify narratives, including a 2023 Republican National Committee ad depicting a dystopian future and AI-edited visuals used by a governor’s campaign to portray a rival in a negative light. Each episode has sharpened calls for clear labeling and provenance tools.

Public concern is climbing as well. Surveys by the Reuters Institute and the Pew Research Center have found that majorities of news consumers worry about distinguishing authentic content from fakes online, with trust further eroded when misinformation appears to come from authoritative sources. Media literacy groups such as the Poynter Institute and civil rights organizations including the ACLU have urged stricter standards for manipulated media in political contexts.

Platforms are experimenting with remedies—from watermarking and provenance metadata to community-driven annotations—but enforcement is uneven. X’s reliance on Community Notes can surface rapid context, yet it comes only after misleading posts begin to spread, and notes do not always reach all viewers.

Why government use of AI-altered memes is uniquely risky

When a government account amplifies altered imagery, the stakes extend beyond a partisan meme. Official communications traditionally adhere to stricter accuracy and transparency norms because they shape public understanding and can influence legal proceedings and reputations. Over the past few years, federal agencies have promoted principles for responsible AI use, emphasizing transparency and harm mitigation—standards that critics argue should apply to imagery shared by the White House itself.

Ethics experts warn that undisclosed edits designed to evoke humiliation or imply distress can mislead audiences about the facts of an arrest and the demeanor of the person detained. Even if the underlying arrest is uncontested, the addition of AI-generated tears materially changes the portrayal and risks undermining trust in official messages.

What to watch next as platforms and officials respond

Expect demands for the post’s removal or a clear disclosure noting that the image was altered. Watch for statements from civil liberties groups, bar associations, and digital rights organizations pressing for government-wide guidelines on synthetic media in official communications.

Platforms will face renewed pressure to label or demote manipulated images when they originate from government accounts. More than a dozen states have already enacted deepfake-related rules for political ads and election periods; while these laws vary and may not directly govern federal communications, they signal a broader shift toward accountability that government actors will find hard to ignore.

For audiences, the playbook remains the same: compare images when a label appears, look for corroborating sources, and scrutinize emotionally charged visuals. In this case, the cross-check was straightforward. The harder question is whether official communicators will voluntarily align with the transparency standards they often champion.