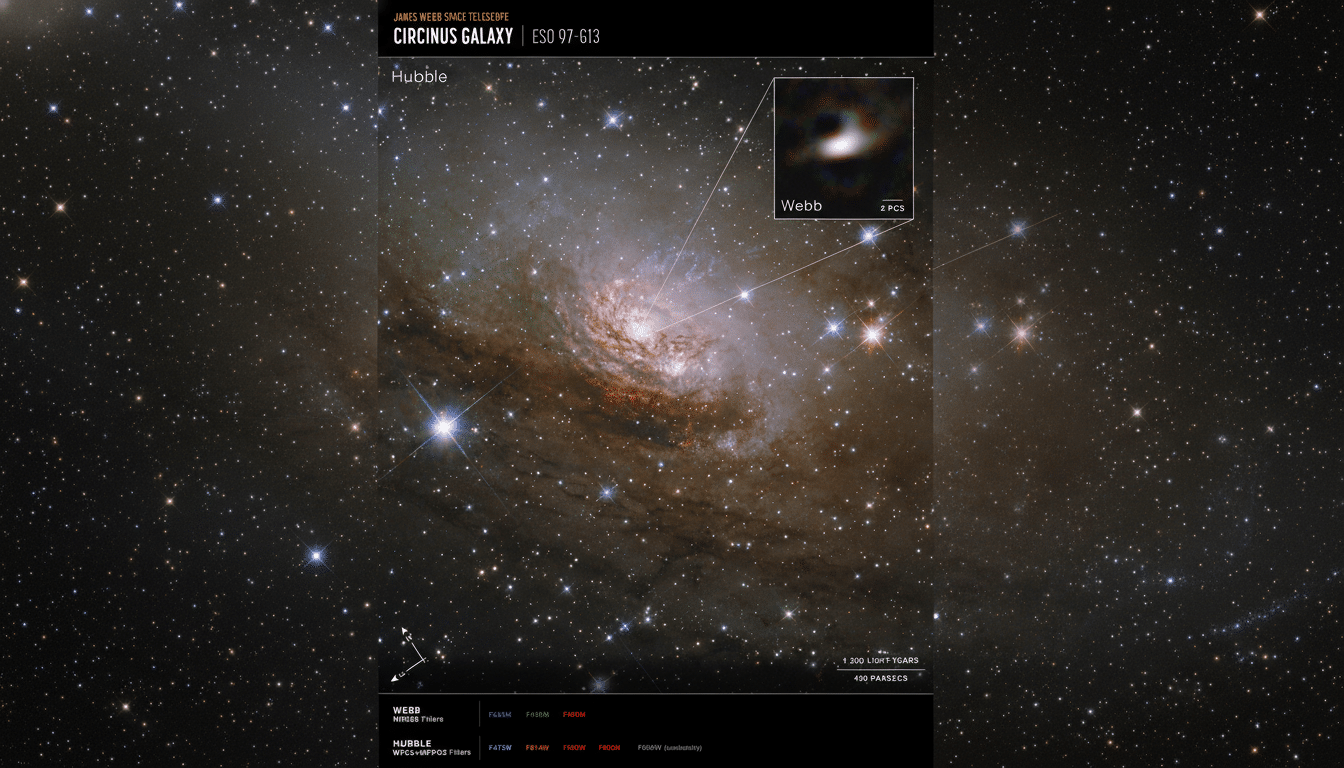

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has captured its sharpest view yet of the cluttered environment fueling a supermassive black hole, revealing that the lion’s share of glowing dust in the nearby Circinus galaxy is packed into a compact, rotating ring that actively feeds the beast. The finding, reported in Nature by an international team, challenges long‑held assumptions about where the brightest infrared emission in such galaxies originates.

Circinus sits about 13 million light-years away, making it one of the closest laboratories for studying an active galactic nucleus. With Webb’s penetrating infrared vision, astronomers separated the light from dust spiraling inward from the fainter glow of material being driven out, offering a rare, close‑in look at a black hole’s “messy” feeding zone.

A Clearer Look at the Dusty Torus Around Circinus

The team reports that roughly 87% of the infrared-bright dust near the galaxy’s core is confined to a dense, doughnut‑shaped ring—known as a torus—that both supplies the black hole with fuel and blocks its glare from certain angles. Less than 1% of that glow comes from outflowing material, the hot “exhaust” that many models assumed would dominate. The rest appears to be distributed more diffusely in the central region.

This result reframes a decades‑old debate in active galaxy research. In the prevailing unification model, a torus of dust and gas explains why some active nuclei look different depending on our line of sight. Yet, since the 1990s, unexplained excess infrared emission hinted that winds or polar dust might be the primary source. Webb’s measurement—in a nearby, well‑studied Seyfert galaxy—puts the torus back at center stage.

“When you count photons, the fuel ring wins,” one coauthor summarized in a briefing supported by NASA, ESA, and CSA. Lead author Enrique Lopez‑Rodriguez of the University of South Carolina notes that earlier models could not simultaneously reproduce the torus component and the extra infrared light, a tension these new data directly resolve.

A Leap in Infrared Interferometry with Webb

The breakthrough hinged on an advanced observing mode: Webb’s Near‑Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph uses an Aperture Masking Interferometer, a seven‑hole mask that turns the telescope into a mini array. By combining the light from multiple sub‑apertures to create interference patterns, the technique reconstructs features at nearly twice the typical resolution over a small field.

At Circinus’s distance, one arcsecond spans about 63 light-years. With the interferometric boost, Webb effectively probed structures down to a few light-years across—fine enough to disentangle the inward‑spiraling dust from faint polar emission for the first time in this galaxy. The team highlights this as the first extragalactic target ever resolved by a space‑based infrared interferometer, opening a powerful path for future studies.

Coauthor Joel Sánchez‑Bermúdez of the National Autonomous University of Mexico emphasized that the method delivers images “twice as sharp,” a critical edge when the science hinges on separating closely packed sources in a turbulent galactic core.

Why It Matters for Black Hole Growth and Feedback

Pinning down where the infrared emission originates is not just a bookkeeping exercise. The balance between accreting material and energy blown back into the host galaxy determines how efficiently black holes grow and how strongly they regulate star formation around them—feedback that galaxy evolution models must capture.

If compact tori dominate the energy budget in many active galactic nuclei, theorists may need to revise how they model dust geometry, radiation transfer, and the coupling between accretion disks and winds. That could shift inferred accretion rates and the predicted impact of outflows, particularly in systems where previous telescopes blended multiple components into a single fuzzy glow.

The result dovetails with other landmark efforts. The Event Horizon Telescope’s image of the M87 black hole mapped hot plasma just outside the event horizon at radio wavelengths; Webb now complements that work by parsing the dusty structures feeding and obscuring the engine at infrared wavelengths. Together with ALMA’s cold‑gas maps and future 30‑meter‑class optical telescopes, a multi‑scale picture is emerging—from sub‑parsec rings to galaxy‑wide feedback.

What Comes Next for Webb and Active Galaxy Studies

The team plans to apply the same technique to a larger sample—on the order of a dozen or two dozen nearby active galaxies—to test whether Circinus is typical. High‑priority targets include well‑known nuclei such as NGC 1068 and Centaurus A, where mid‑infrared polar dust has been reported. With Webb’s interferometric mode, astronomers can quantify how much of the glow truly comes from compact tori versus winds across diverse environments.

For now, Circinus offers the cleanest case yet that the black hole’s main meal comes from a tight, obscuring ring rather than from the material being blasted away. In a field where geometry dictates what we see and what we miss, Webb’s zoomed‑in view delivers the crucial context: before a black hole can blow a wind, it must eat, and most of the heat we detect is coming from the dinner table itself.