Wearables for health are increasingly commonplace, used to monitor blood pressure, glucose, sleep, and activity. Now a new peer‑reviewed analysis issued Thursday weighs the hidden cost of this trend: if current design and end‑of‑life management trends for our devices persist, by 2050, e‑waste from outdated TVs, mobile phones, and computers will weigh more than that produced by all plastic packaging, resulting in an estimated 100 million tons of carbon emissions driven primarily by energy use during manufacturing and disposal.

The study, conducted by researchers at Cornell University and the University of Chicago and published in Nature on Wednesday, estimates annual demand to climb to 2 billion units by mid‑century — about 42 times today’s volumes. That scale is such that even subtle design choices have global implications.

- Why Small Gadgets Can Carry a Surprisingly Big Footprint

- The Fast Track from Fitness Wearables to Clinical Use

- Putting a Million Tons of Wearables E‑Waste in Context

- Design Levers That Can Bend the E‑Waste Curve for Wearables

- Economics and Policy Are as Important as Engineering

- What to Watch Next as Wearables Scale in Health Care

Why Small Gadgets Can Carry a Surprisingly Big Footprint

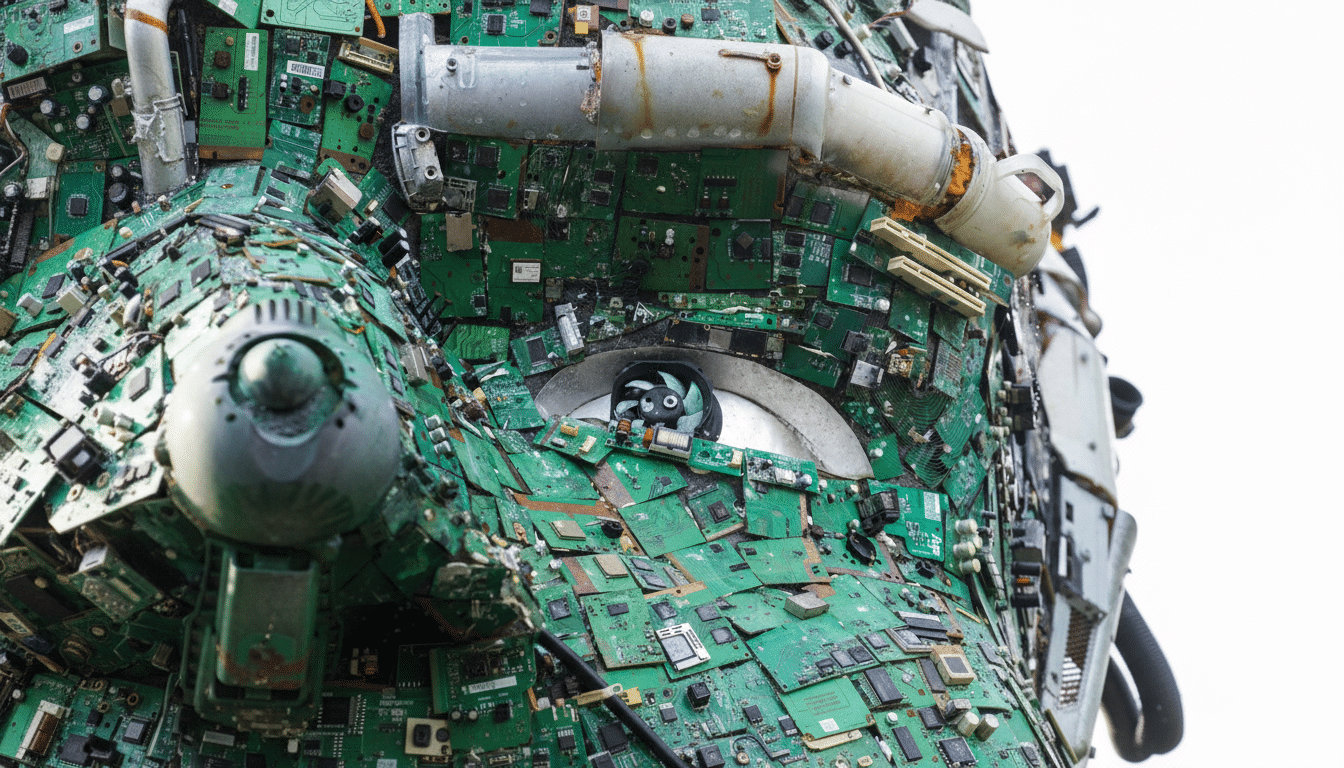

Contrary to instinct, plastic shells are not the climate offender. The printed circuit board (PCB) — the device’s miniature “brain” — is by far the most impactful emitter, representing an estimated 70% of a wearable’s life‑cycle carbon footprint. These are energy‑ and chemical‑intensive processes: mining and refining precious metals such as gold and palladium before turning them into ultra‑dense boards.

Miniaturization compounds the problem. Adhesives, over‑molding, and sealed batteries secure coveted high water‑resistance ratings but do so at the cost of making disassembly slow and expensive, lowering the odds that recyclers can recover valuable metals at end of life.

The Fast Track from Fitness Wearables to Clinical Use

Wearables are moving from step counters to medical‑grade companions. Continuous glucose monitors, cuff‑less blood pressure sensors, and ECG‑capable watches are being funneled to care pathways through RPM programs or through employers’ or insurers’ incentives. That mainstreaming brings more people closer to health data — but also drives up device churn as people upgrade for better accuracy, new sensors, or a covered replacement.

Fleet management, standard in clinical settings with bulk deployments, swaps, and stringent hygiene requirements, can reduce life cycles even further if products are not designed for refurbishment and component reuse.

Putting a Million Tons of Wearables E‑Waste in Context

The world produced close to 62 million metric tons of e‑waste in the most recent accounting year, and only about 22% was formally collected and recycled, according to the United Nations’ Global E‑waste Monitor. In that context, a million tons of stuff from health wearables is a drop in the bucket — but a very challenging one. They are light, copious, and ill‑assorted in material; they readily skate past formal recycling channels and dribble into drawers, where recovery rates drop to zero.

And the carbon intensity rises. If those pieces are not recovered, the sector’s share of emissions goes up even if the total mass feels small.

Design Levers That Can Bend the E‑Waste Curve for Wearables

The Nature study suggests that some of these are simple engineering moves with an outsize payoff. First of all, re‑spec components to use as little or no precious metal as possible and replace them with copper, for example, and other standard materials where electrical requirements allow. Large‑scale orders of simple minimizations in the low‑ to mid‑single digits, scaled to billions of units, can significantly reduce upstream emissions.

Second, make wearables modular. When housings, straps, and sensors can be upgraded while core logic boards and batteries are kept or remanufactured, the most high‑impact parts get a second (or third) life. Think cartridge‑style sensor pods, standardized board footprints, and mechanical fasteners replacing single‑use adhesives, all without compromise to water resistance.

Battery strategy matters, too. Replaceable cells extend lifetimes and make recycling easier for the end user. New EU battery rules point in that direction for portable electronics, and eco‑design guidance increasingly focuses on disassembly as well as the availability of spare parts and software support that aligns with anticipated hardware lifespans.

And at the cutting edge, energy‑harvesting methods that use resources such as thermoelectric or motion power from sensors, and low‑power chipsets, can eliminate or shrink batteries in some applications. For flexible printed electronics, using recyclable substrates would simplify materials complexity and recovery.

Economics and Policy Are as Important as Engineering

Manufacturers respond to incentives. Extended Producer Responsibility systems based on eco‑modulated fees can offer incentives to design modular products and punish products that are difficult to dismantle. Deposit‑return programs for health wearables — delivered by retailers, insurers, or clinics — could raise take‑back rates far above today’s levels.

A number of the most prominent smartwatch and sensor brands already operate trade‑in and refurbishment programs, but they are currently directed at premium devices. Reaching low‑cost trackers and medical sensors is crucial, as they frequently ship in high volume and turn over more quickly.

Transparency helps. Transparent notices about material content, battery type, and anticipated software support allow buyers to balance environmental performance as well as product features. Both repairability scores as well as independent teardowns from groups like iFixit have shown that adhesives and integrated batteries are significant bottlenecks; addressing them early in design leads to dividends.

What to Watch Next as Wearables Scale in Health Care

Signs that the curve may be bending include:

- Higher health wearables take‑back rates

- Longer device lifetimes for remote monitoring programs

- Higher recovery of PCB metals per unit

If procurement criteria from hospitals and insurers begin to prioritize circularity as well as accuracy and cost, expect the industry to follow quickly.

From the research, the message is clear: The health benefits of wearables do not need to carry an equally sized environmental bill. With thoughtful material selection, modular design, and savvy policy, the industry can remain on a virtuous course — even as it welcomes billions of new devices online.