Venture capital mogul Vinod Khosla is pushing the U.S. government to buy a 10% stake in every public company, which would be held together in a national fund that could help soften the social and economic blow of artificial general intelligence. Characterizing it as a way to universally distribute the gains of AI, Khosla contended that an equity-based safety net could help preserve social cohesion in an age of accelerating automation.

A Radical Equity Buffer for the Coming AGI Era

Khosla’s pitch is simple: as AI enhances corporate margins and productivity, some of that upside should just automatically flow to the public. Referring to the government’s choice to take a 10% stake in Intel during the Trump administration, he cited it as an inspiration for thinking at national scale. And it wouldn’t be a one-time bailout or subsidy; instead, he imagines the government holding a permanent pooled stake in each key company that pays dividends and appreciates with the market over time.

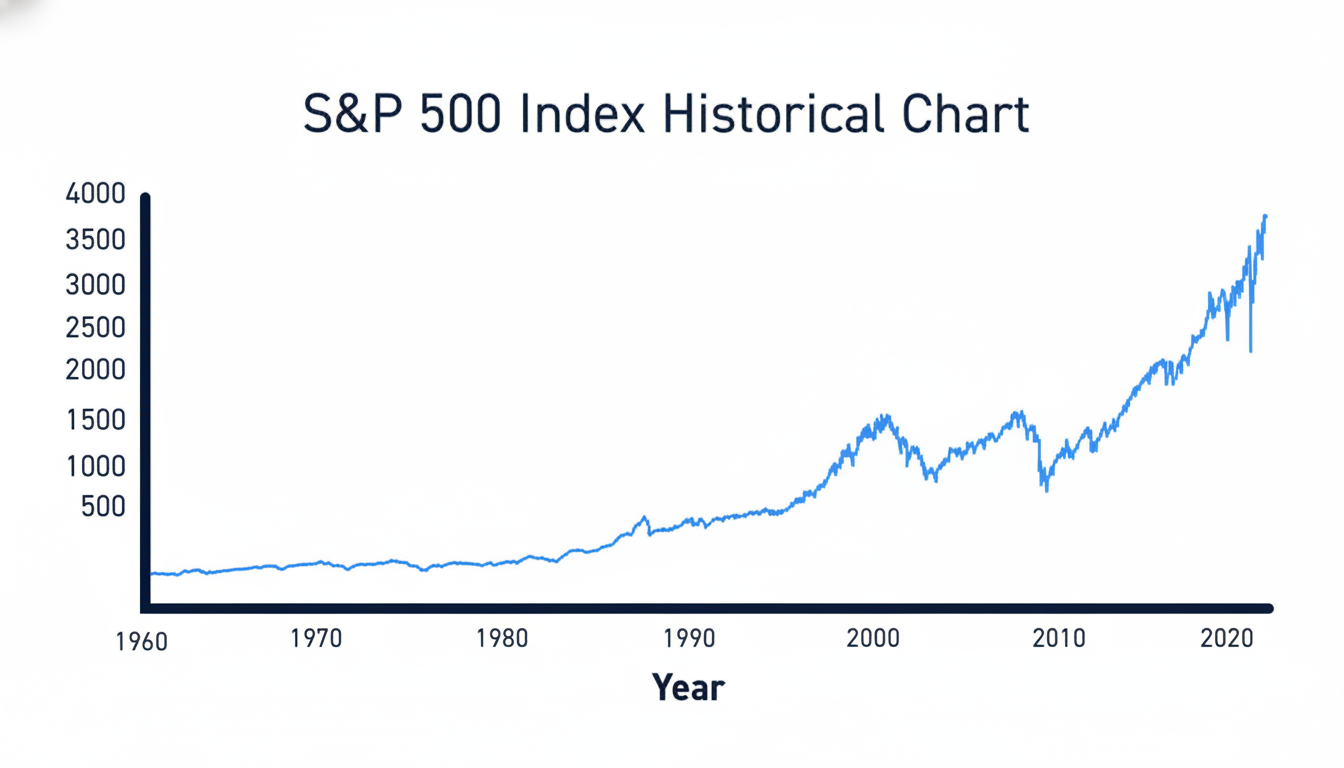

Scale matters. The market capitalization of U.S. public equities is estimated to be about $50–55 trillion by different measures; and a uniform 10% holding would total roughly $5 trillion at today’s prices. And if the S&P 500’s dividend yield drifts around 1.4–1.7%, such a pool could generate $70–90 billion in cash per year at scale, without even accounting for capital gains—resources that we might allocate towards an “AI dividend,” income supplements, and targeted reskilling.

There are past examples of a similar kind of people’s stake in national wealth. The Alaska Permanent Fund writes checks to citizens each year using oil fees. And then there is the Government Pension Fund Global of Norway, which invests proceeds from oil in global equities for future generations. Khosla’s twist is to socialize a piece of corporate equity itself as AI reorganizes where value gets created.

Policy Mechanics and Legal Hurdles for a National Stake

Enforcing the piecemeal 10 percent government stake would be a legal and political quagmire. Stakes would probably have to be paid for under the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause. Congress would also have to specify how shares are acquired (tax-for-equity swaps, phased purchases or warrants), what voting rights would be exercised or waived, and how proceeds are distributed among citizens.

There are models to study. In the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. Treasury seized preferred stakes and warrants in major banks as part of TARP and ultimately made a profit. The U.K. and Sweden, during banking crises, used temporary state equity, then exited. Champions of a more permanent approach cite ideas for a national social wealth fund that policy wonks love — controlled independently and beyond the reach of politicians who might meddle in corporate governance.

Governance would be a flashpoint. (Focusing a 10% claim across all listed companies could change shareholder votes, boardroom dynamics and executive pay.) One compromise is to keep nonvoting shares or delegate voting to independent fiduciaries under clear guardrails, similar to how large index funds already handle conflicts today.

UBI Comparisons And Evidence From Cash Pilots

Khosla’s thinking dovetails with longstanding conversations about universal basic income. OpenResearch, supported in part by Sam Altman and others, has researched the impact of long-term cash transfers at scale. Early findings from random pilot projects such as Stockton’s SEED program and a basic income experiment in Finland have indicated improved financial stability and well-being, with few downsides when it comes to employment. In the United States, the temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit has also been shown to have had a major effect on lowering child poverty by analyses from Columbia’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Equity could support annual cash payments in perpetuity, without increases in taxes at least over the near term, provided that returns outpace distributions. Opponents say that market downturns could put payouts at risk, and there are calls for a more diversified funding base that blends equity returns with the accustomed tax money.

Jobs at Risk and Where AI Gains Actually Accrue

Fear of losing jobs is what drives Khosla’s urgency. According to the International Monetary Fund, AI could displace as much as 60% of jobs in advanced economies including a large share that may be automated. McKinsey forecasts that generative AI will help automate or supplement most knowledge work tasks, from accounting and legal research to customer service and design, leading to millions of job transitions in the U.S. by 2030.

Productivity research indicates that the gains are real but unequally spread. In trials of coding copilots, developer speed has jumped by double digits; companies that are using AI to serve customers say they resolve problems faster and save money. If owners of capital take in most of that wealth gain, an equity-based dividend, Khosla suggests, is one tool to balance the books — especially during what he sees as a potentially deflationary transition.

What to Watch Next as Debates Over AGI Wealth Sharing

Markets would probably resist mandated dilution, and there would be questions from civil libertarians about state ownership in private businesses.

Labor and some economists might be prepared to accept a sovereign equity buffer if it’s designed in such a way that would protect against political pressure.

Budget hawks will want to know how the government funds its initial purchases and deals with risk on the national balance sheet.

Even if Khosla’s 10% idea remains aspirational, it is establishing a negotiating position: as AGI nears, the argument is moving from regulation to how the wealth that emerges from it is divided. Whether through a national equity fund, targeted taxes or some hybrid mechanism, policy makers now ask the same fundamental question — who owns AI’s upside and how widely should it be shared?