The British government renewed its effort Monday to get access to encrypted messages, this time focusing on stored copies of data and bypassing the encryption when it comes to clients who are dealing with terrorists or kidnappers. That put Carlos A. Godez, left, the general manager of a popular bakery and pizzeria in Tijuana, Mexico, in danger of losing everything as much from virus-induced economic pain as from actual infection. The effort is focused on a closed-door demand that Apple build a way for police to get at data in accounts protected by the company’s “Advanced Data Protection” part of iOS 15.

If implemented, the order would compel Apple to weaken safeguards that are meant to be so strong not even the company can read a user’s content stored on its servers. Privacy advocates and security engineers generally argue that any backdoor, even in private hands, is a threat to the overall system — one that can be exploited by criminals, hostile states or rogue domestic actors.

What the reported new UK demand is seeking from Apple

The fight is over U.K. user iCloud backups (which include device backups, messages, and photos) that are stored in the cloud under Advanced Data Protection, Apple’s opt-in end-to-end encryption for most of the categories of family members’ data it processes when users select “full account” access to those families. FT reports that the Home Office last month sent a fresh technical order requesting that Apple help them create a tool that would allow cloud backups from suspects’ devices to be decrypted at the request of British police forces.

Such orders are typically confidential. They can force a provider to “undesign” products or services so that data are available under lawful authority. Apple has repeatedly said it won’t create a backdoor or master key, claiming that special access can’t be used solely when appropriate.

How the Investigatory Powers Act uses TCNs in the UK

The request is reportedly made under the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, which sets out the extent of surveillance, data retention, and interception powers in the UK. The law permits the government to issue a “technical capability notice,” or TCN, which compels companies to retain or develop tools that enable it to carry out warrants. These notices can have extraterritorial effect and are controlled by judicial commissioners and the Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Office.

In theory, a TCN can compel an operator to make interception possible — but even then only where there is a test of technical necessity and proportionality. Notices can be challenged by the companies receiving them, and any task required by a notice must be practically feasible without fatally weakening overall service security. Security experts say end-to-end schemes with a zero-knowledge architecture don’t pass that test, because it only takes weakening one group of users to weaken everyone.

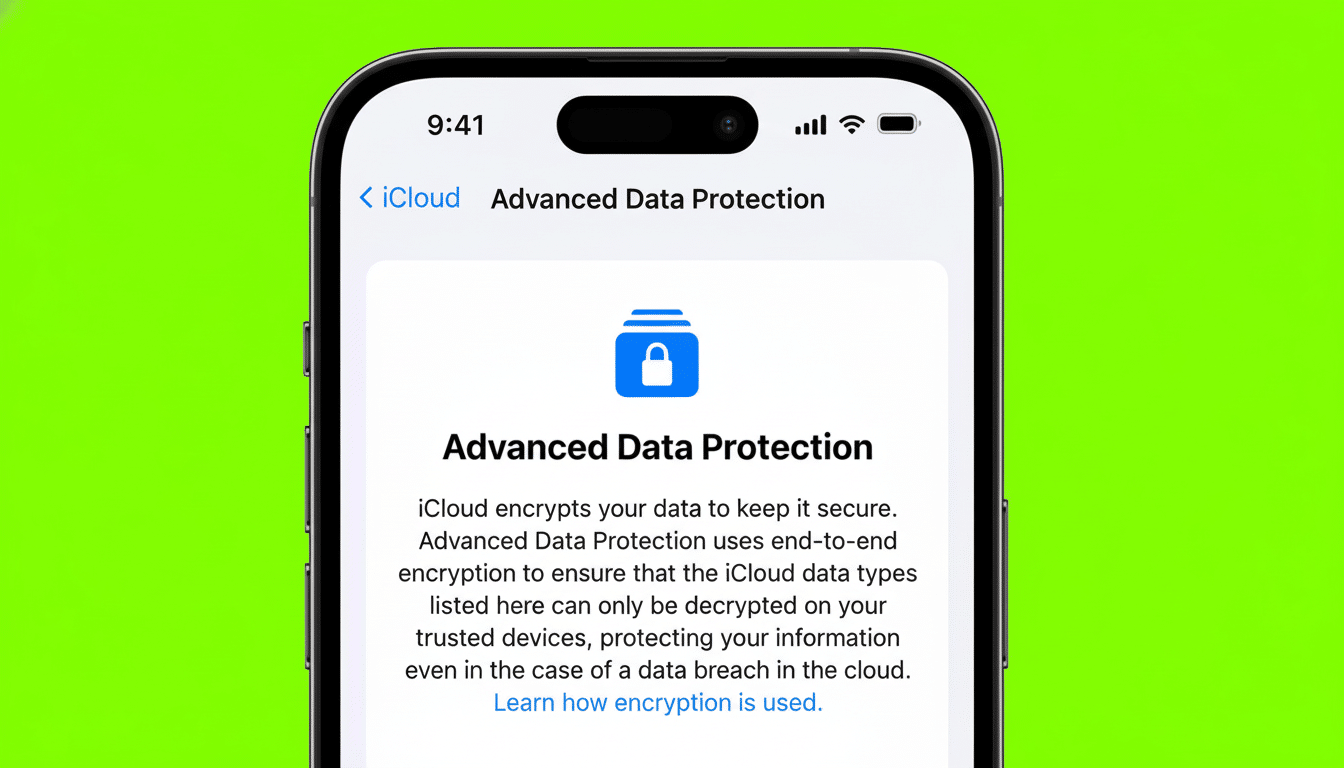

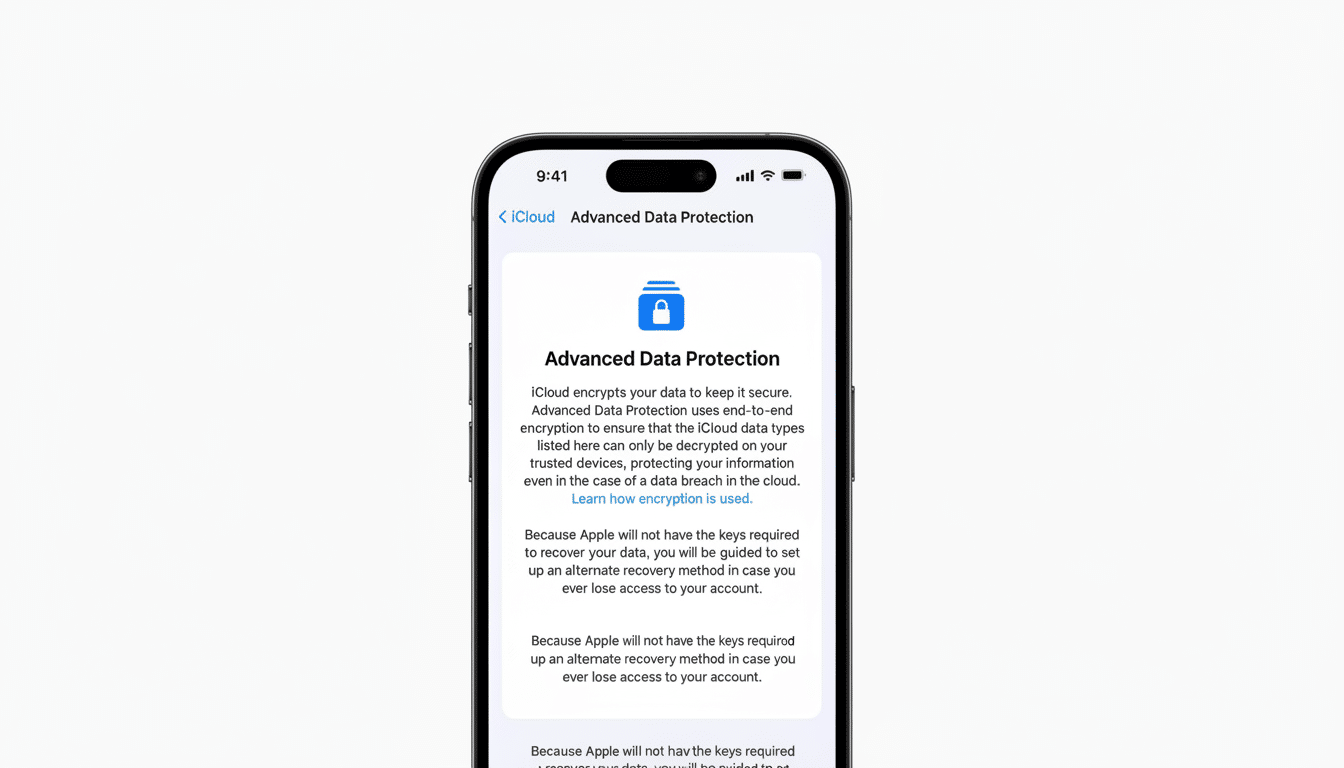

Apple’s encryption approach and Advanced Data Protection

Apple announced Advanced Data Protection to bring end-to-end encryption to iCloud backups and other categories including Notes and Photos, where the user is in control of the keys. The company claims it would be unable to provide access to ADP content when compelled by law even if it wanted to, because it doesn’t have the keys (which Apple, at some future date, would take away from government) — a security posture intended precisely to uphold unilateralism by either Apple or government.

Apple’s position is informed by lessons learned from past situations, including the row over unlocking an iPhone in a U.S. terrorism case and repeated efforts to push “exceptional access,” as it is often called around the world. Apple also cites its transparency reports, detailing thousands of device and account requests from authorities annually to which the company generally responds — when such data exists and legal standards are satisfied — but says it does not have access to end-to-end encrypted content in a technical sense.

Security Stakes And The Child Safety Argument

The UK government usually justifies access requests by reference to serious crime and national security, with child safety frequently referenced in the encryption debate. Ideas like client-side scanning — which would inspect content on a user’s device before it is encrypted — have been proposed as a compromise. But cryptographers and top academics caution that client-side scanning nevertheless amounts to a surveillance mechanism that can be redirected, and weakens the end-to-end nature of certain systems.

Security researchers say that breaches always pick the lowest fruit, and any backdoor will become an irresistible high-value target. This is not an academic risk: How rapidly special access systems can be converted to wider harm has been demonstrated through recent public disclosures of compromised encryption keys and stolen passwords.

Global Context And Possible Repercussions

What happens here will be felt far beyond the U.K. The extraterritorial nature of the Investigatory Powers Act could pit British legal obligations against those of other countries, including American statutes and constitutional protections. The industry is closely monitoring the case because any precedent that forces architectural changes to end-to-end encryption could potentially lead to similar demands from other governments.

Messaging platforms and cloud services have already told regulators they might turn off features or withdraw service rather than retool global infrastructure for one jurisdiction. Privacy groups have said that loosening end-to-end encryption would harm at-risk communities, including journalists and activists as well as survivors of domestic abuse, and undermine cybersecurity for businesses that use cloud services to protect sensitive data.

What to watch next in the UK Apple iCloud dispute

Look for a legal and political process, not a quick technical change. All of those notices can be contested, and other “eyes” such as independent oversight mechanisms should assess the proportionality and feasibility of forcing decryption for ADP-protected accounts. Should Parliament do so, it would also be weighing in on changes to surveillance laws that might shape how capability notices could be used.

At least in the short term, Apple is almost certain to stick to its position that there should be no backdoors. The fundamental issue — can a government compel a provider to unmake end-to-end encryption for some subset of its users without making everybody less safe? — remains as open, and important, as ever.