TuneIn is plugging into the country’s official emergency pipeline, and bringing authorized alerts from FEMA right to vehicle dashboards and mobile streams so drivers can hear critical warnings in real time. By connecting to the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System, which provides the backbone for broadcast and wireless alerts of imminent threats, TuneIn will provide verified geotargeted signals about severe weather, natural disasters and other hazards as they become available while you’re behind the wheel.

How TuneIn’s FEMA-powered alerts work and interrupt audio

FEMA’s IPAWS delivers authenticated messages from local, state, tribal, territorial and federal authorities through the Common Alerting Protocol. TuneIn sees those CAP fields—severity, urgency, certainty and targeted area—and makes a determination how to display the notice. Less severe advisories, like hydroplaning-inducing downpours or thunderstorm wind gusts, will scroll across the bottom of the screen as unobtrusive alerts; life-threatening events such as tornado or flash flood warnings can interrupt with an audible alert and visual prompt.

- How TuneIn’s FEMA-powered alerts work and interrupt audio

- Why real-time alerts matter for drivers and road safety

- Where drivers will hear alerts in cars and mobile apps

- Privacy, permissions and user control for targeted alerts

- How it fits into the U.S. emergency alerting system

- Limitations, reliability and the role of redundant channels

- What to expect next as TuneIn rolls out IPAWS integration

Geofencing is key. Alerts are tied to the polygons or FIPS codes of affected areas that alerting agencies have submitted, so drivers hear whatever they need to know for their exact location rather than receiving a general, one-size-fits-all message. That cuts back on noise and makes it less likely that when a broadcast is broken into, we are being pulled off track for something that really deserves our attention.

Why real-time alerts matter for drivers and road safety

Weather can be a huge driving risk.

The Federal Highway Administration estimates that there are about 1.2 million weather-related crashes a year in the United States, causing some 5,000 deaths and over 418,000 injuries. Just-in-time alerts of fast-moving dangers that can come with a storm — whiteouts, flooded roads, unexpected crosswinds — could alter routes and slow speeds and save lives.

The trend line is worsening. A record 28 U.S. weather and climate disasters with damages in excess of a billion dollars were recorded by NOAA in 2023, highlighting the frequency at which high-impact events are impacting communities. Bringing National Weather Service warnings and other IPAWS alerts into car audio reduces the gap from when a warning is issued to when it’s acted upon, which can be critical in making life-saving decisions.

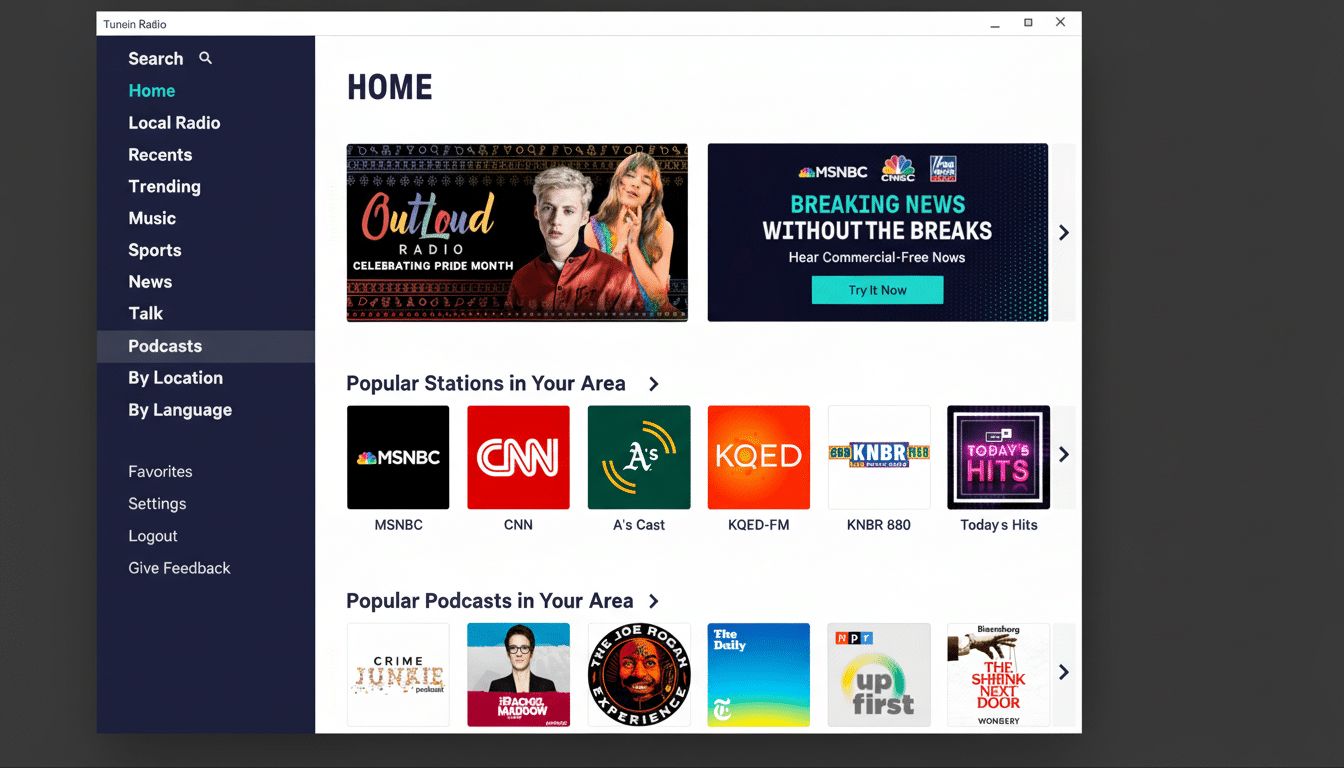

Where drivers will hear alerts in cars and mobile apps

TuneIn’s alerting will appear through native integrations inside vehicles or from the mobile app using Apple CarPlay or Android Auto in cars. The company’s service is already integrated in vehicles from Rivian, Lucid, Tesla, Jaguar Land Rover, Mercedes-Benz, Volvo and Sony Honda Mobility (among others), meaning the coverage is now modern infotainment stacks — not just those that rely on AM/FM interventions.

And because IPAWS is the source of truth behind the scenes, those messages emanate from the same authorities local drivers already depend on — emergency management offices, the National Weather Service and public safety agencies — but now zapped over a platform already familiar to most commuters for news reports, sports updates and tunes.

Privacy, permissions and user control for targeted alerts

Location targeting provides precision, but it also triggers familiar concerns about data usage. Best practice for alerting apps is clear: seek (explicit!) permission, collect as little data as possible, and let users adjust what they receive. You can also presumably hope for fine-grained controls over which types of alerts will actually wake you up; with options to silence non-emergencies but not life-threatening challenges.

For safety, we have to care not just about how the audio performs. Good implementations gradually ramp volume up, do not overly distract and switch back to programming soon after the alert is given — just like broadcast radio or TV stations do with their Emergency Alert System alerts.

How it fits into the U.S. emergency alerting system

IPAWS drives both the Wireless Emergency Alerts that appear on phones and the Emergency Alert System used across broadcasters. The area of streaming audio has long been a hole in that ecosystem, which means drivers who depend on apps rather than AM/FM are more likely to miss time-sensitive warnings. Integration with TuneIn is closing that gap, adding FEMA-authorized messages to one of the largest digital audio platforms in the world.

The Federal Communications Commission is responsible for the EAS rules and system tests, while FEMA is in charge of IPAWS and does validation of alerting authorities. By following CAP and FEMA’s modus operandi, TuneIn becomes one more compliant distribution method – not a separate and/or competitive system.

Limitations, reliability and the role of redundant channels

Streaming is a device-reliant mode of media consumption; disasters can damage or disrupt cellular networks. That makes the new feature a complement, not a replacement, for terrestrial radio and other channels’ resilience. Redundancy is the point of IPAWS — phones, broadcasters, sirens and now also streaming audio all working together to maximize the likelihood that the right person hears (or rather sees or feels) the right alert at the right time.

For drivers, the practical advice is straightforward: Keep several alerting channels open, update your apps when you can and check location permissions so that geotargeting can do its part. In a situation where seconds matter, saving even a little time between warning and action can mean everything.

What to expect next as TuneIn rolls out IPAWS integration

As rollout expands, we might expect more direct automaker support, finer-grained control over the interrupt levels, and multi-language alerts where the agencies provide them. The most important stat will not be the number of downloads or the hours listened to — it’ll be when a timely warning makes sure a driver doesn’t drive into that flooded underpass, needs to detour around the forest fire or pulls over before hailstones shatter the windshield. That’s the kind of potential having IPAWS in the modern car would bring.