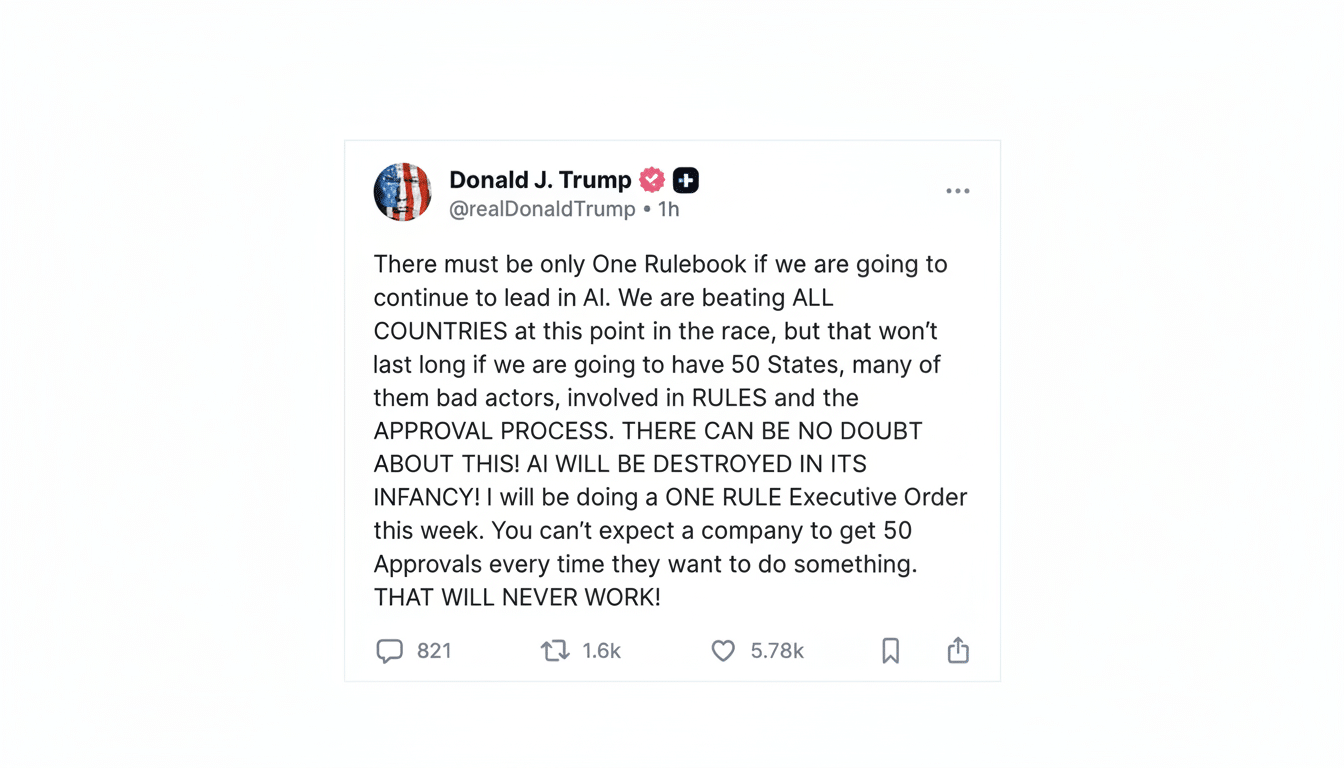

President Donald Trump’s new executive order on artificial intelligence indicates a single “national rulebook” for the technology. In reality, that could leave startups marooned in potential legal limbo as Washington battles the states over who can set the rules and just how far preemption can go.

The order directs the Department of Justice to establish a task force within 30 days to challenge state AI laws, instructs the Commerce Department to identify “onerous” state provisions within 90 days and nudges the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Communications Commission to explore federal standards that could preempt those set by states. It also urges Congress to approve a model law.

The promise is clarity. What will probably happen in the near term is litigation. A president’s executive order cannot simply wipe a state law off the books, absent congressional action. That could leave the current patchwork, and not much else, stretched into a long transition period, young companies whipsawed by ever-changing state-by-state rules while federal courts and regulators weigh in.

What the Executive Order Actually Does Do

At its heart, the order tries to bring a fight over AI regulation into the center. DOJ likely will rely on constitutional arguments — particularly the Dormant Commerce Clause — to make the case that state-by-state AI rules overly restrict interstate commerce. Commerce may also attempt to shape behavior by linking federal grants and programs with compliance to federal guidance — a well-worn lever in tech and broadband policy.

But the order does not on its own impose legally binding federal standards. Courts have to determine if any state provisions are preempted, and agencies must propose and finalize whatever rules they want to enforce. That typically involves a matter of months, if not years. Even if preliminary injunctions would freeze some state requirements, appeals could keep them in flux across the country.

Supporters say wading into the debate in Washington tamps down chaos. Critics say court fights only exchange one uncertainty for another. Advocacy organizations like the Future of Life Institute have lambasted the approach as preferential toward incumbent platforms, and industry trade associations say only Congress can provide a lasting, risk-based federal framework.

A Patchwork of AI Rules That Continues to Spread

In 2024, the National Conference of State Legislatures tracked more than 400 AI-related bills among the states; momentum will continue in 2025. Several measures have real teeth. Colorado’s AI Act, which becomes effective in 2026, lays obligations on “high-risk” systems, among them risk mitigation, assessment of impact, reporting of incidents and consumer disclosure. New York City’s Local Law 144 mandates independent bias audits and provides notices for automated employment decision tools in use in the city. California’s privacy regulator is developing rules on automated decision-making under the CPRA, which could bring access and opt-out rights for some AI uses.

These regimes do not align. States and cities have different definitions of “high-risk,” audit scopes, documentation and disclosure triggers. What’s “high-risk” in a model fine-tuned for recruiting might not be in one jurisdiction but would be elsewhere; transparency text that can pass muster in one market may fall short in another. The EU’s so-called AI Act, which is rolling out in 2025–2026, introduces a new layer for startups with global customers to address compliance assessments and post-market surveillance.

The Costs of Staying in Compliance Hit Startups First

For early-stage squads, the logistical weights are right now. Most independent bias audits can easily run into five figures per tool. Recorded risk management (per NIST AI Risk Management Framework) involves ad hoc staff time in engineering, security, and legal. Insurance carriers are demanding tighter model governance, and sales to regulated buyers — banks, hospitals, schools — increasingly turn on detailed AI assurance packages.

Take a seed-stage company that uses AI to power hiring. To sell in New York City, it would be required annually to conduct a bias audit and post public notice; to operate in Colorado, it would need to prepare risk assessments, include adverse-impact disclosures and plan for incident reporting; in California, the company may even have to develop opt-out flows and human review pathways once ADMT rules are on lock. Every additional demand lengthens sales cycles and grows the attack surface for class-action risk if disclosures fall short.

Larger platforms can absorb the costs with compliance teams and standard playbooks. Startups are more likely to put off deployments or restrict market coverage, which dulls competition. Some lawyers caution that long-term uncertainty could create the worst of both worlds: de facto consolidation as Big Tech waits out the courts, along with uneven protections for consumers in the meantime.

Preemption Fight Moves To Court And Congress

DOJ objections will probably focus on aspects determined to be extraterritorial or technically prescriptive in a manner that interferes with interstate commerce. States with marquee laws such as Colorado and California are preparing to defend their role, particularly on issues that are based in consumer protection or civil rights. Anticipate mixed early rulings and forum shopping until appellate courts set clearer limits.

Meanwhile, agencies can shape the field without new statutes. The FTC has already employed its authority under Section 5 to police deceptive claims about AI and unfair data practices, including insisting on algorithmic disgorgement in prior cases. NIST’s framework is starting to appear as a standard in procurement and vendor questionnaires. But only Congress can pass a comprehensive law that has preemption, enforcement and definitions that hold up in court.

David Sacks, the administration’s AI and crypto policy lead, has pushed for a national standard that applies everywhere, arguing startups need predictability. Trade groups representing app developers and small firms have echoed the push for a federal baseline that is risk-based. Privacy and safety advocates argue that federal preemption without robust safeguards could diminish accountability in the places where harms are most acute.

Bottom Line for Builders Navigating AI Rule Changes

The order represents a real move toward federal primacy, but it does not make for an immediate “one rulebook.” Startups should budget for at least another year of overlap:

- Track important state obligations

- Harmonize documentation to NIST, where possible

- Budget for independent audits when they make sense

- Build disclosure and human-in-the-loop controls that are flexible by jurisdiction

The hope of national clarity may come — by the courts or by Congress — but the future remains like a maze.