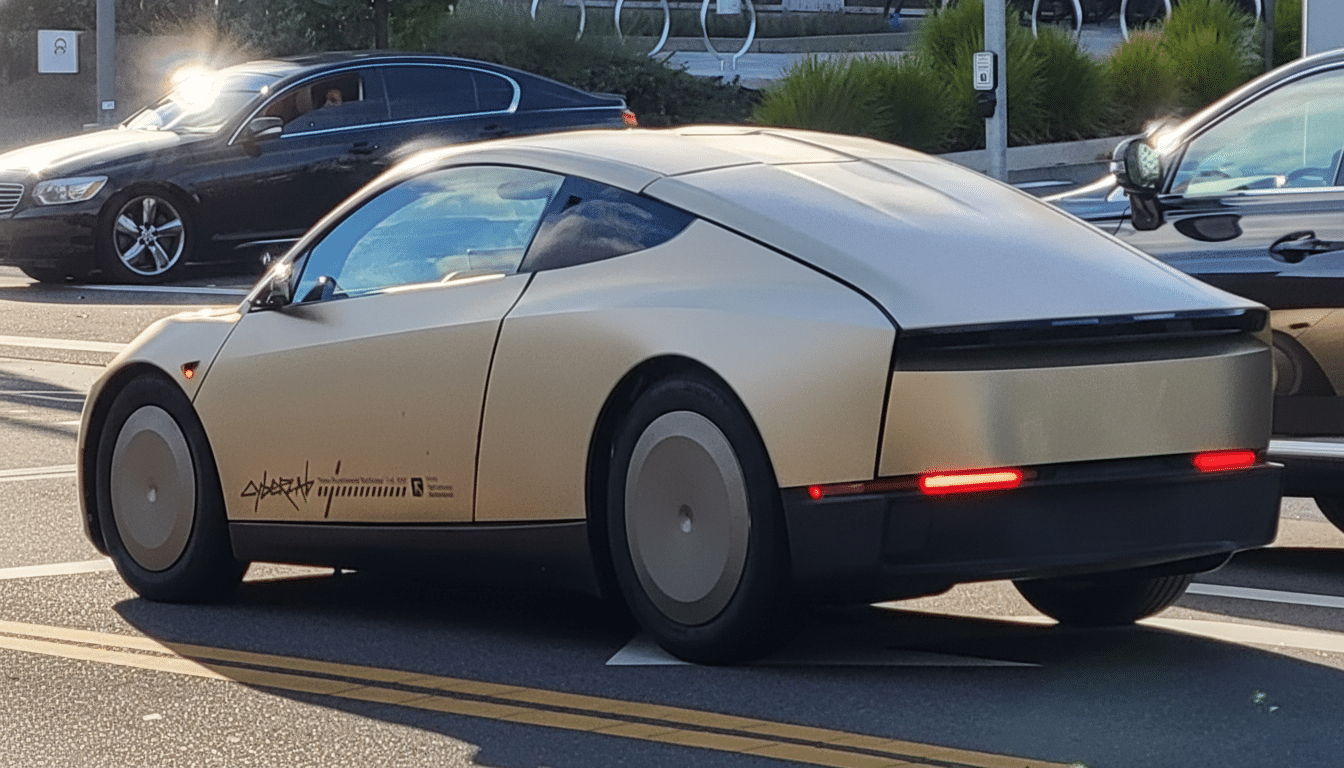

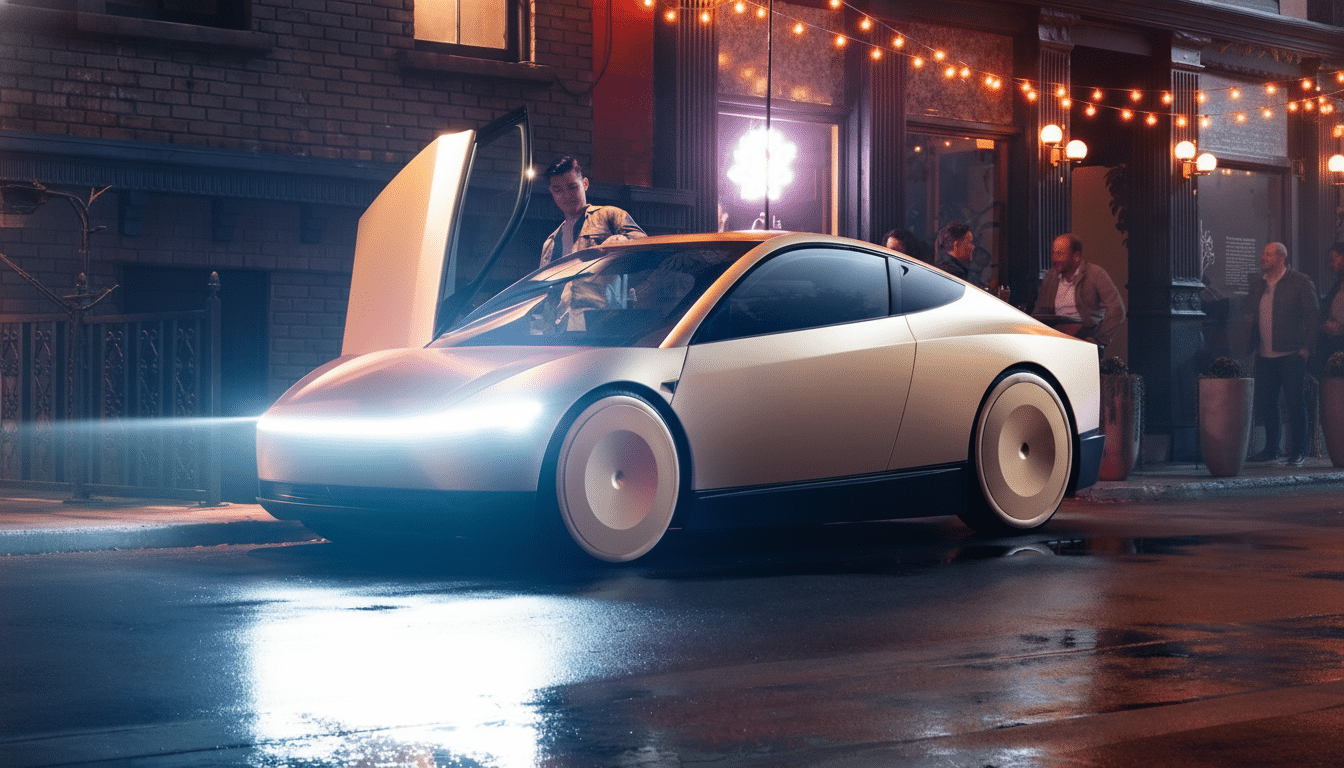

Tesla will begin producing its long-promised Cybercab in April at the company’s factory in Austin, Tex., the chief executive Elon Musk told shareholders, describing the vehicle as a robotaxi that is purpose-built without a steering wheel, pedals or side mirrors. The promise fronts a high-stakes timeline for Tesla’s autonomy ambitions, and it raises immediate concerns about the manufacturing pace, regulatory approval and real-world readiness.

The announcement came as investors were buoyed by Musk’s wider vision of autonomy-fueled growth. But Tesla must still show that it can do actual driverless operations at scale. Its smaller robotaxi operation in parts of Austin is currently using Model Y vehicles equipped with a new “unsupervised” version of Full Self-Driving software, with an employee in the passenger seat.

A robotaxi with no manual controls or traditional interfaces

The Cybercab is designed to be the cheapest vehicle that you can own and the lowest-cost-per-mile vehicle by removing traditional controls, packaging space effectively with no wasted room, while creating an extremely serviceable user experience.

That vision seems to contradict recent comments from Tesla chair Robyn Denholm, who had indicated that a backup steering wheel and pedals had been under consideration. The internal tensions illustrate how design aspirations can run into regulatory realities in designing a vehicle that will drive itself, without any human behind the wheel.

Removing manual controls transfers the technical burden to software and system redundancy. Tesla is still working on a camera-only perception stack, differentiating itself from rival companies like Waymo and Zoox, who also use lidar and radar sensors in conjunction with high-definition maps. A vision-first approach helps cut costs, but it also requires top-notch performance in foul weather, unusual lighting and unusual edge cases — conditions that separate a promising demo from a scalable robotaxi service.

Aspirational line speed and volume targets for production

Musk noted the Cybercab production line will aim for a 10-second cycle time, significantly less than the ~1 min takt time he said for Model Y. On paper that could be 2–3 million Cybercabs per year — an unprecedented ramp for a full-stack AV new entrant.

If achieved, the throughput would reshape urban mobility’s supplier side in one stroke.

But volumes are constrained by more than line speed. There are multiple bottlenecks that can slow down output, from battery cell availability to power electronics and software validation. For context, the company shipped about 1.8 million cars in 2023, it said in its filings. Million-robotaxi production would also require tight charging hubs, high-uptime maintenance operations and fleet software optimized for utilization over 50% — the point at which per-mile economics begin favoring robot ride-hailing over doing so with humans.

Tesla has suggested that its “unboxed” production process, big gigacastings and structural battery packs will crush cost and complexity. The innovations have potential for step-change efficiency — but only if yield, repairability and the readiness of suppliers grow alongside. To hear it, aggressive cycle-time targets will continue to be a gamble instead of a given — at least, not until that time arrives.

Regulatory hurdles loom for control-free robotaxis in U.S.

Producing a car without steering wheel and pedals requires federal exemptions from U.S. safety standards. The Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration still assume manual controls will exist. Exemptions are generally limited to 2,500 vehicles per year and awarded for a finite amount of time. Amazon-backed Zoox secured an exemption to test its bespoke robotaxis on public roads, and it’s interesting that General Motors has suffered a lot of delays in getting approval for the Cruise Origin to be deployed at scale. Waymo, the largest U.S. robotaxi provider by service footprint, still operates modified vehicles with conventional controls and is co-developing a custom-built version with Zeekr.

There are two ways Tesla could ultimately go: ask for an exemption for a control-free Cybercab or start with manual controls to roll out faster, while data is being reviewed by regulators. Vehicle design is subject to federal rules nationwide, while states regulate operations. Any quick ramp depends on NHTSA’s comfort with Tesla’s safety argument and validation — crashworthiness, fail-operational capability, operation at the ODDs.

Musk didn’t seem bothered, suggesting that when driverless rides become the norm, “people will no longer have an issue” with them. But regulators generally are swayed by evidence. Performance metrics that can be measured — disengagement figures, incident rates per million miles, and clear reporting for when things go wrong — will matter more than timelines.

What to watch next as Tesla pursues April Cybercab production

If April production is real, signs of momentum will quickly emerge:

- Tooling and hiring in Austin

- Filings for federal exemptions

- Buildouts of charging and maintenance depots

- Early geofenced deployments

Also watch whether the initial Cybercabs include controls: that will telegraph Tesla’s read on regulations, for better and for worse.

For cities and investors, the scoreboard is straightforward: cost per mile, uptime, safety and rider adoption. If Tesla can get to low-$0.50 per mile with high utilization, then the economics for urban trips change rapidly. Like their taxis-on-tarmac analog, if autonomy gets stuck in traffic or cross-exemptions get delayed at green lights, Cybercabs imperil themselves by becoming a high-capital resource parked outside the door, waiting for permission and proof. The next few quarters will determine whether Tesla’s biggest bet becomes a manufacturing triumph, a test case in transportation regulation or both.