Tesla has released a more detailed safety report for its Full Self-Driving (Supervised) system, responding to pressure from industry rivals and safety advocates for more transparency. The new car crash disclosures — which have definitions, methodology and comparative rates of crashes per mile — bring Tesla closer to the kind of data Waymo has long made public about its driverless operations.

What Tesla’s new FSD safety report actually says

Tesla’s most recent numbers state that drivers using FSD (Supervised) experience a major accident about once every ~3 million miles and a minor one around ~1 million miles. According to NHTSA, typical U.S. driving results in one crash about every 505,000 miles and one “close call” (commonly called a fender bender) about every 178,000 miles. On the surface, that would seem to be an advantage for FSD users compared with average human driving exposure.

- What Tesla’s new FSD safety report actually says

- How Tesla defines and categorizes collisions in FSD data

- The Waymo context behind Tesla’s latest safety disclosures

- Interpreting miles per collision in real-world conditions

- How It Differs From Tesla’s Previous Reports

- What regulators and experts are watching for

The company also says it will refresh the dataset quarterly, utilizing a rolling 12-month aggregation to emphasize more recent performance as software iterates. Tesla also points out that it doesn’t publish injury metrics because the dataset is taken automatically from cars, instead using surrogate triggers (like airbag deployment) as a proxy for severity.

How Tesla defines and categorizes collisions in FSD data

For the first time in Tesla’s manual, definitions are based on Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards. Severe crashes are those in which there is a high likelihood of risk of injury, and the airbags or other pyrotechnic restraints that are not reversible deploy. Sideswipes are lower-severity crashes that do not activate those systems.

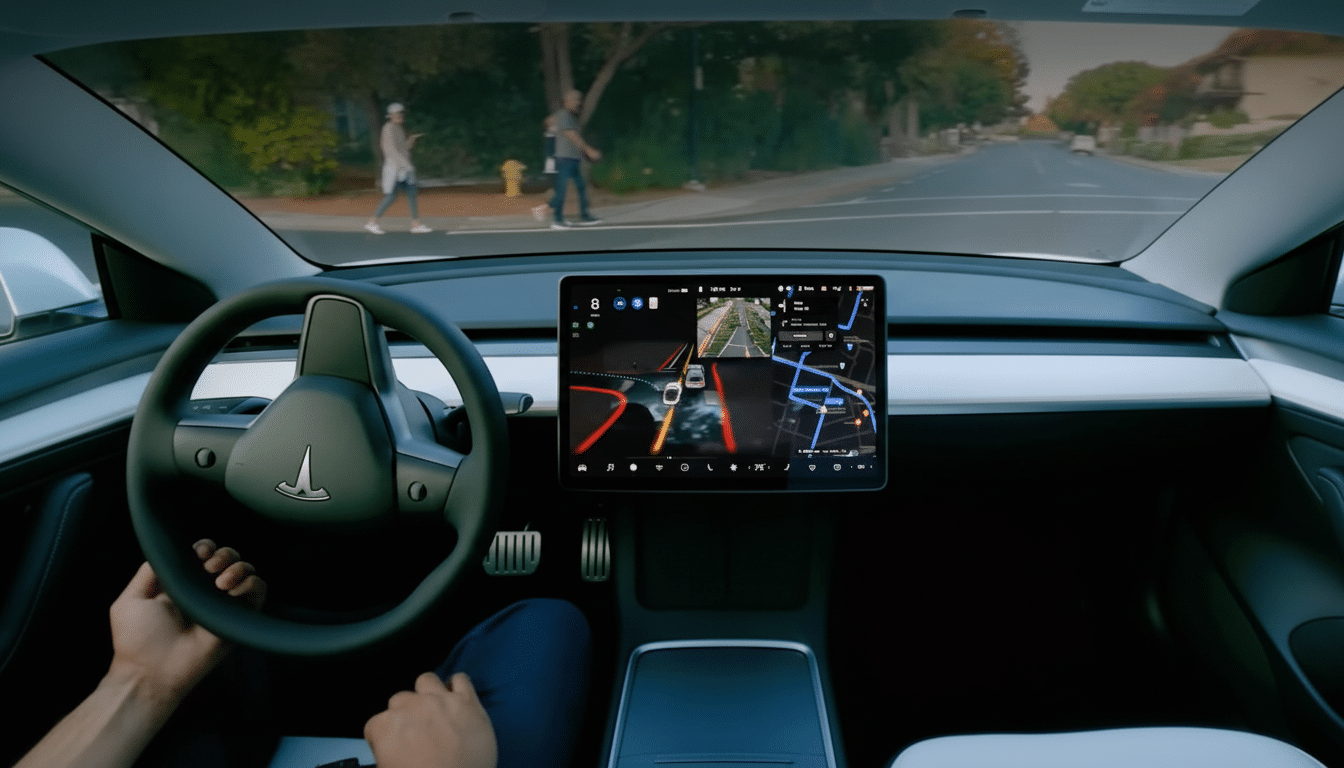

It’s also worth noting that Tesla includes a crash in the FSD dataset if FSD was engaged at any point within five seconds of impact. That framing is significant: it’s meant to stop undercounting episodes in which a driver disengages FSD moments before a crash, or when “the system aborts on its own.” Methodologies like these have proved sticking points in debates over how to account for safety when it comes to automated driving.

The Waymo context behind Tesla’s latest safety disclosures

The report comes after Waymo’s co-CEO publicly called on competitors to share more data on the safety of their fleets. Waymo has released peer-reviewed quantitative analyses and multi-year reports of safety that show its driverless service operates many times safer than human drivers, all told, and even more so in pedestrian-involved contexts. The difference is crucial: Waymo’s day-to-day core service is driverless in mapped, geofenced locations, while Tesla’s FSD (Supervised) continues to require a human behind the wheel at all times.

That difference in operating design domain and supervision model makes direct comparisons difficult. Waymo’s miles are in dense urban areas under heavy constraints; Tesla’s FSD spans a wider variety of conditions at the cost of safety-critical human oversight. Even so, the move to release uniform definitions and rates from Tesla will close the comparability gap and address growing pressure for transparency in all automated systems.

Interpreting miles per collision in real-world conditions

Miles per collision is intuitive but imperfect. Exposure varies by speed, type of road, time of day, weather, and traffic conditions, all influencing the chance and severity of a collision. Highways, for one thing, generally experience fewer but more serious crashes; urban streets have higher rates of low-speed contact. Without a split by scenario, a system that is more often operated on favorable roads might appear safer than it really is when considered on an equal footing.

Tesla’s reliance on airbag deployment as a proxy is an industrywide standard that can be acceptable in some circumstances, but it excludes injuries not severe enough to activate airbags and other outcomes such as near-misses or system disengagements. Researchers at groups such as the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and the AAA Foundation have long been calling on vendors to release more information about exposure — things like night-driving share, pedestrian intersections, unprotected turns, and bad weather — in order to make better comparisons across systems.

How It Differs From Tesla’s Previous Reports

Past Tesla safety reports focused on Autopilot, a highway-based assistance suite, and drew fire for comparing highway-weighted performance to national averages that include all fatal crashes. The new, FSD-focused breakdown tackles some aspects of that by splitting up a feature set and explaining the window for including events. It also addresses a major concern identified by safety analysts: making sure that collisions are counted regardless of control transition timing at the time of impact.

That said, the report remains devoid of injury and crash-type specificity, and it does not yet drill down into how well (or poorly) Tesla’s handful of limited robotaxi pilots staffed by safety drivers operated, based on miles between intervention — a threshold that’s even closer to rival fleets providing driverless services.

What regulators and experts are watching for

Regulators and independent analysts are likely to concentrate on three things:

- The consistency of methodology over time

- Disaggregated exposure by road and environmental factors

- How software updates tie into crash patterns

NHTSA probes of misuse and crashes in incidents related to driver help show why comparative, standardized reporting is essential for public trust.

With quarterly updates and increased scenario-level breakdowns to supply fuller context on disengagements and near-misses, the Tesla dataset might become a significant benchmark alongside the safety libraries released by Waymo or industry reports issued by certifiable safety bodies. For now, Tesla’s move toward more precise definitions and mileage-based rates is a significant step — one driven, in part, by industry pressure to show its work.