Chris Anderson, the ad-man-turned-mogul who has long been TED’s curator and TED’s face, is putting together a $300 million vehicle to attack the toughest choke point for climate tech technology: financing first-of-a-kind plants for products that can replace planet-cooking ones. The All Aboard Coalition is designed to write catalytic checks that propel companies from proven pilots to the $100- to $200-million growth rounds needed to launch initial commercial facilities — exactly where most promising climate hardware startups face bottlenecks.

The promise isn’t that $300 million will simultaneously bankroll steel, cement, fuels, batteries and grid-scale storage at commercial scale. It’s that the fund functions as a signal amplifier, leveraging a deep bench of seasoned climate investors, the crowd-in of generalist growth equity, infrastructure capital and strategics that often wait for someone else to de-risk the first project.

Why the “missing middle” gap matters

Physics is the moat in climate tech, and it’s the money sink. Construction of a FOAK (first-of-a-kind) plant—a long-duration battery factory, an e-fuels plant or a low-carbon cement kiln—frequently takes nine-figure checks before banks start looking at project financing. Venture funds want R&D or software-scale velocity; infrastructure funds want stable cash flows and brownfield performance. That chasm is the valley of death.

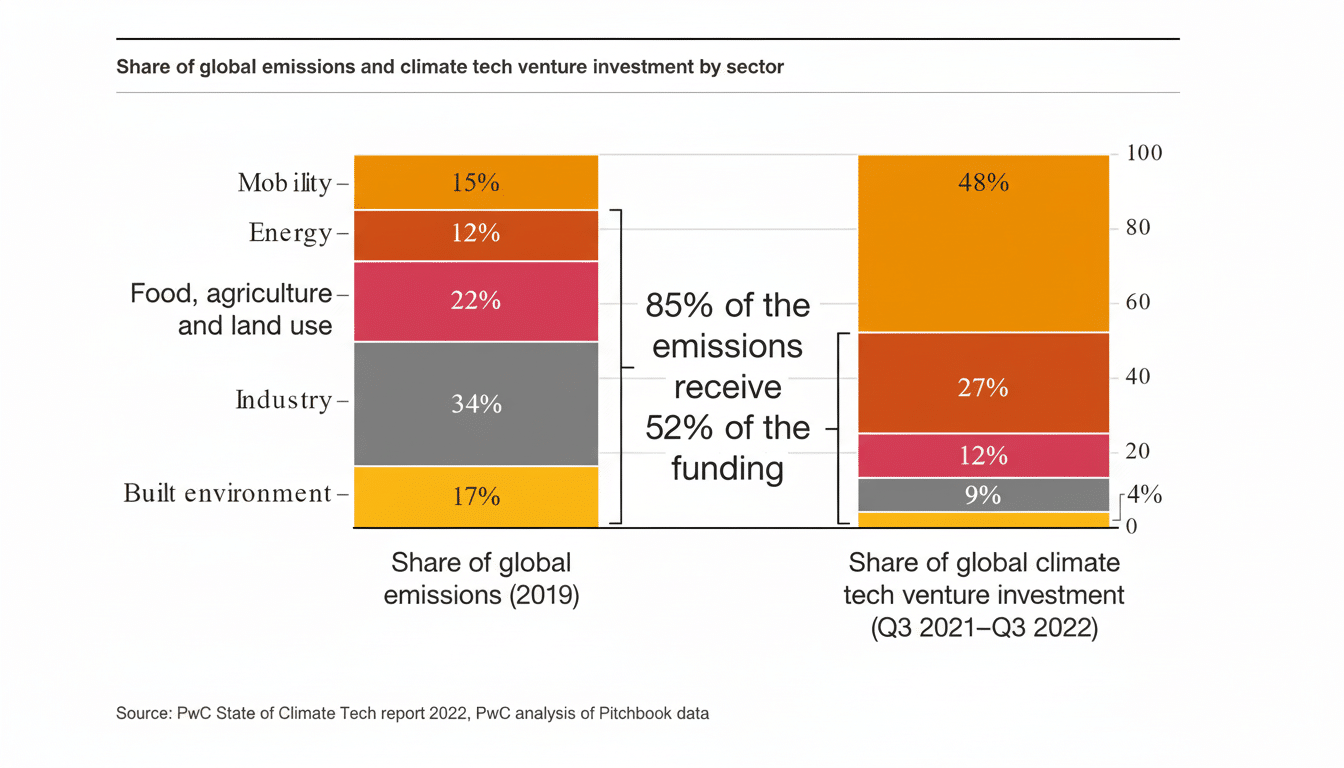

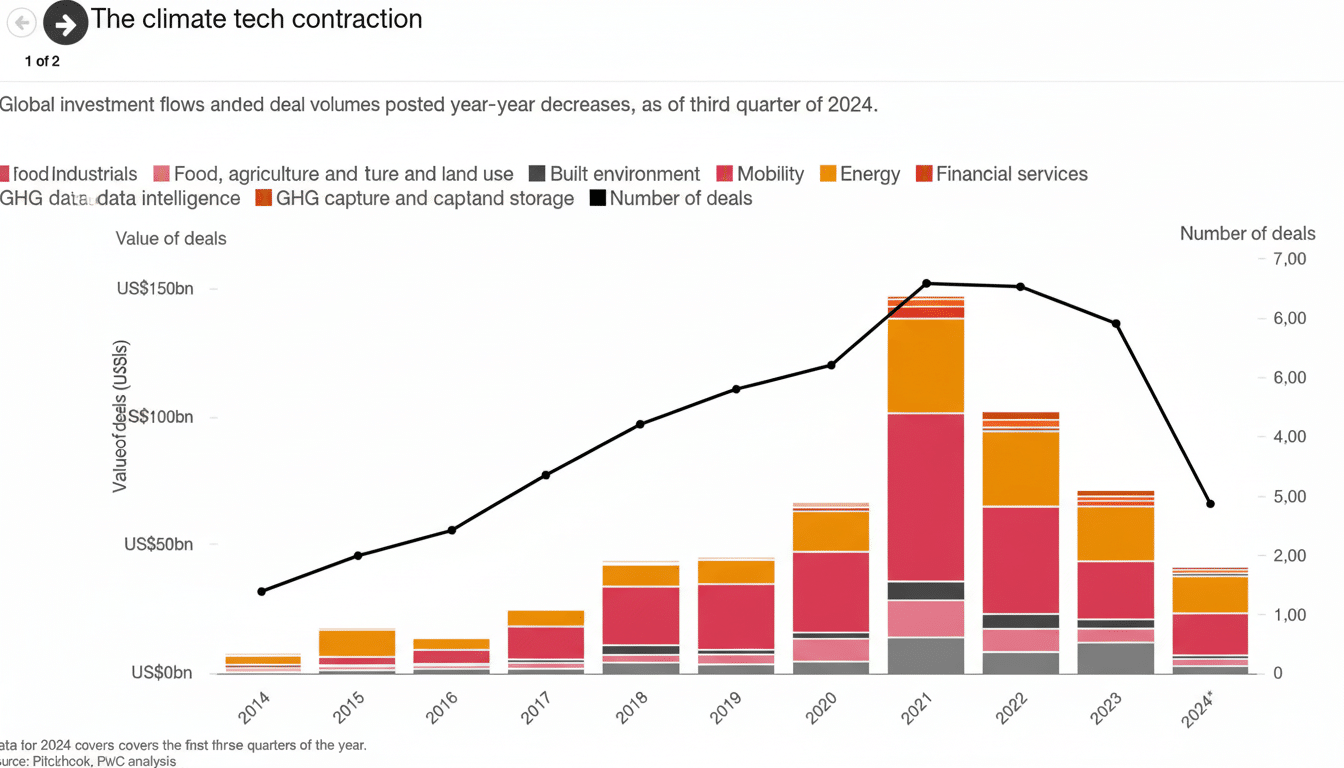

Early-stage activity proved more resilient, but PWC’s State of Climate Tech analysis recently found that late-stage climate venture finished 2023 down sharply. Project finance is plentiful for proven industrial technologies, like utility-scale solar and wind already amply in place, but scarce for unproven industrial processes, BloombergNEF has observed. The net result: More developed use cases and companies with strong pilots only to struggle finding a buyer or making the economics of the first commercial unit work to unlock cost curves and bankability.

The stakes are large. The International Energy Agency says investment in clean energy recently eclipsed $1.7 trillion, but the bulk of it, notably, goes to technologies long understood. Decarbonizing heavy industry and long-duration storage requires a bridge from lab to large — where technical risk, EPC complexity and offtake uncertainty all intersect.

How All Aboard aims to de-risk FOAK

Anderson’s coalition includes everyone who’s anyone in climate investing — firms like Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Energy Impact Partners, Khosla Ventures, Galvanize Climate Solutions, Prelude Ventures, DCVC, S2G, and others. Not every firm needs to invest, but their participation creates a due-diligence flywheel: Once a company passes this group’s bar, the signal is meant to bring in larger checks from pensions, sovereign funds, corporate balance sheets and crossover investors.

The strategy plays to strong public-finance levers. The Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office has more than $400 billion in lending authority to support innovative projects; the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations offers grants and cost-share for near-commercial deployments. On the tax front, the transferability provisions from recent Congressional acts make credits such as 45Q (carbon capture), 45V (clean hydrogen), 45Z (clean fuel production) and 48C (advanced manufacturing) simpler to monetize, thereby sweetening the FOAK economics without additional equity dilution.

Think of All Aboard as the equity spark that gets us over the capital stack finish line: a cocktail of structured equity, equipment finance, government guarantees, and offtake-backed revenue that nudges projects past the investment committee.

Where capital can move the needle most quickly

Long-duration energy storage: Companies developing iron-air, thermal or flow batteries will need pilot plants to demonstrate grid-scale storage for multiple days. FOAK projects at the $150-300 million scale can justify multiple year contracts on both performance and capacity payments to utilities.

Industrial heat and materials: Lower-carbon cement, steel and process heat (such as thermal batteries) would utilize innovative kilns, electrolyzers, and high-temperature systems. A single successful commercial pipeline could reduce costs 20-40% through the standardization of engineering and supply chains and by making follow-on project finance more accessible.

Clean fuels and carbon: Sustainable aviation fuel and e-fuels plants—along with modular direct air capture or biogenic carbon removal—are starving for construction capital and bankable offtake. Early units can apply 45Z and corporate procurement to guarantee revenue while the performance data de-risks the next wave.

The power of an authentic seal of approval

With venture, the participation of certain firms really reduces perceived risk. All Aboard is trying to replicate that dynamic for later-stage climate hardware: a syndicate whose collective diligence is a verdict that the technology, unit economics and execution plan have met a high bar, and whose board-level support is a signal that these can bring the technology, but most importantly the company, to scale.

If it works, the multiplier is more important than how big the fund may be. A multiplier of two to five from generalist and infrastructure investors would transform $300m into $600m to $1.5bn for FOAK builds — sufficient to take various sub-sectors through to the “nth-of-a-kind” phase at which cost curves bend sharply.

Risks, guardrails and what to watch

$300 million is a down payment, not an all-inclusive strategy. It is success is dependent on rigorous portfolio construction, close alignment with public co-investment, and off-takes that lock in margin over the commodity cycle. Allowing, grid connection, EPC access and supplychain risk are some of the nontrivial risks of execution.

There will be a desire by investors to see transparent governance to resolve potential conflicts between member firms, strict criteria for FOAK readiness, and evidence of crowd-in from pensions and insurance capital. Operational KPIs: number of initial plants financed, time to provision to commercial operation, the leverage ratio of incremental project finance unlocked per dollar deployed.

The climate capital stack is starting to fill out: early venture for science, government for demonstrations, and infrastructure money for scale. The missing link has been a concerted bridge to the first true plants. If All Aboard comes through with the signal — and the syndicates — Anderson’s $300-million wager might just be the right small, smart wedge to open a very big door.