Strava is poised to go public, wagering that the age of social running and group workouts has arrived as the new manner in which young consumers meet, chat and keep one another accountable. The fitness platform’s resonance with Gen Z — who have emerged as more keen on community-focused, booze-light activities than endless swiping — has produced a holy trinity of growth, culture and monetization that public investors lust for.

IPO momentum and monetization plans fuel Strava’s growth

The company’s chief executive, Michael Martin, has said the company intended to go public when market conditions were more favorable and that fresh capital would be used for acquisitions and product expansion, The Financial Times reported. Its backers include Sequoia Capital, TCV and Jackson Square Ventures, and the company’s most recent valuation was around $2.2 billion.

The growth story is compelling. Sensor Tower estimates that Strava now has some 50 million monthly active users, almost double the size of its next nearest fitness rival — and downloads are up about 80%, year over year. When last tallied, subscription spend via app stores had exceeded $180 million, a figure Strava contends understates overall revenue because of direct billing and partnerships. The monetization mix also includes more than just premium memberships: it counts sponsored challenges, brand activations and race partnerships as revenue lines that dovetail well with its community-first model.

An IPO would formalize what insiders already perceive: a software company that cashes in on motivation. The bet is that a sticky social graph around movement — who you run with, where you ride and how often you train — will create recurring revenue streams and cohort retention.

Gen Z swipes less as they chase splits and community runs

The surge at Strava mirrors a larger cultural shift. Studies by research firms like McKinsey and the Global Wellness Institute have pointed to younger consumers’ hunger for community-first experiences and wellness-led socializing. Group runs and track nights, along with other club meetups, are seen as a form of friend-finding by members — and sometimes even a little dating — while the mental health benefits are an often-cited major draw.

Running events are also riding the wave. The London Marathon has said applications to the race increased 31 percent, with just over 1.1 million people entering a lottery for the chance to run, and parkrun has announced record attendance figures at free, community-based weekly 5Ks. For many in their teens to early twenties, running clubs serve as a modern “third place” — structured and inclusive (and cheap) — where exercise and friendship overlap.

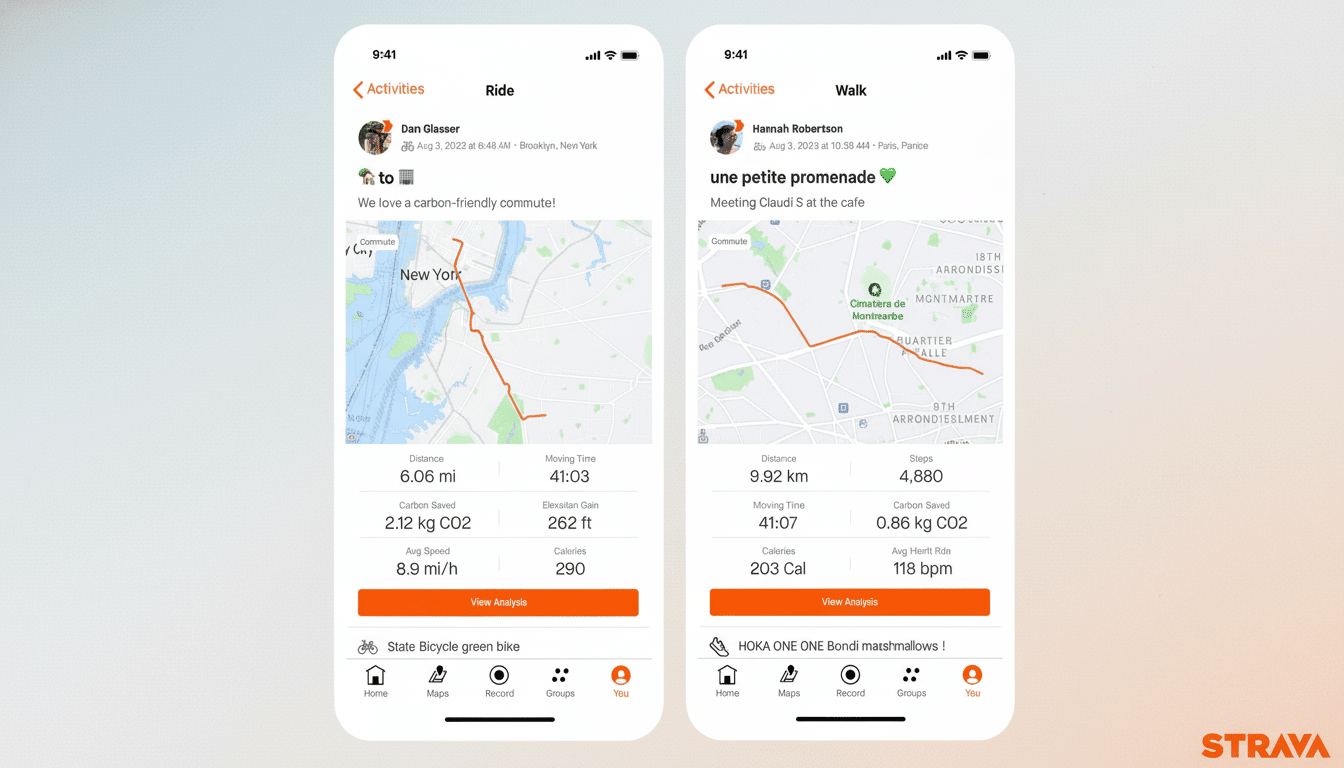

Strava’s product is designed for this transition. Kudos, segments and club feeds turn miles into social money. “The purpose of posting splits is not so much to performance peacock as it is to participate,” she says, adding that a shared language like this helps lower the barrier to entry and keep groups together between meetups.

Product flywheel and community features drive engagement

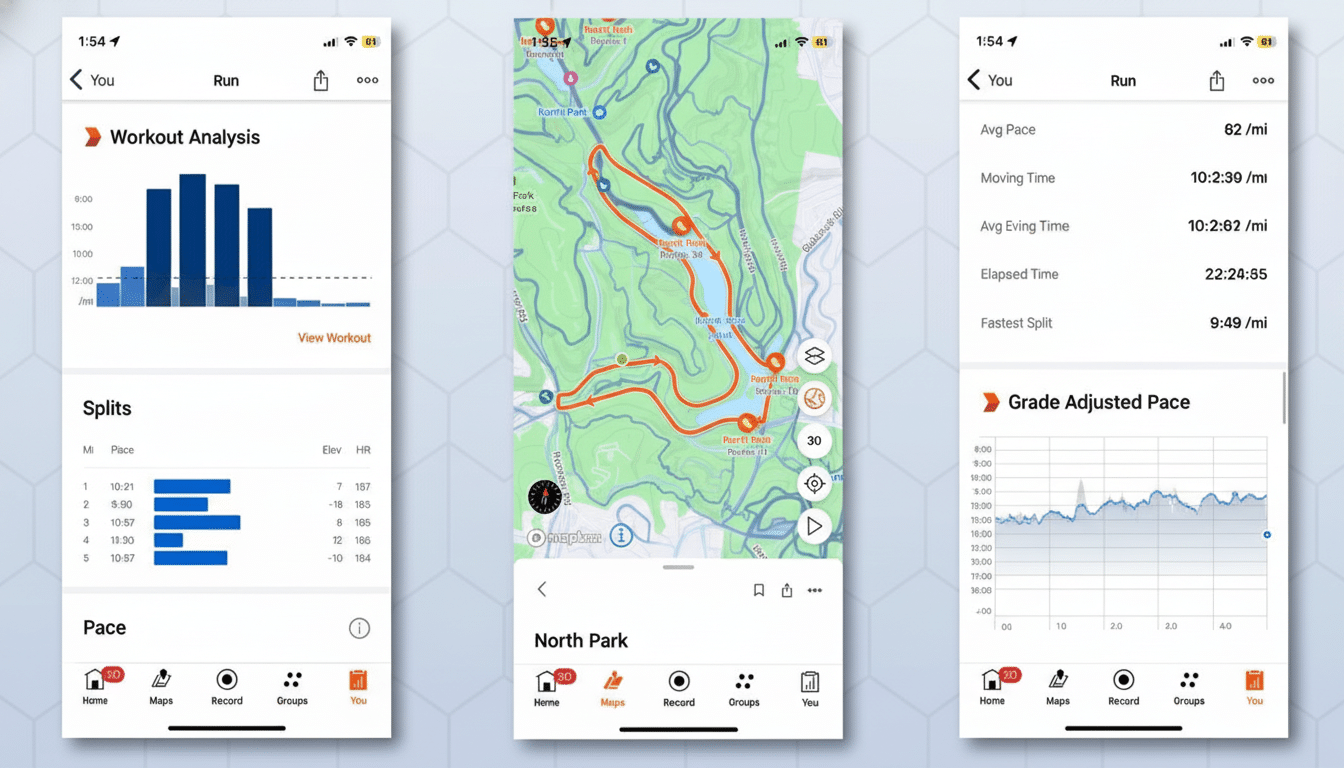

The flywheel of the platform is simple: community, content, habit, conversion to search. Explore is driven by route discovery and heatmaps. On long runs, I also like to use safety features, such as Beacon. Club features allow coaches and leaders to set group challenges that spill over into real life. Brands and races bestow an overlay of accomplishment through badges, prizes, or early entry.

Strava has also used acquisitions to further fill in its toolkit. And when it acquired FATMAP, high-resolution 3D terrain and planning hit the platform, a game-changer for trail runners and cyclists. If the IPO goes through, expect similar acquisitions in mapping, coaching or creator tools as Strava courts both everyday athletes and the larger class of run-club organizers who define local scenes.

Competitive landscape and risks facing Strava’s expansion

The field is crowded. Apple includes fitness features right in its devices, Garmin locks in serious athletes with hardware and analytics, and Nike Run Club and Adidas Runtastic continue to be popular gateways. For Strava, it’s not the equipment that sets it apart; it’s network effects forged from shared bragging rights, encouragement and accountability across brands and devices.

Risks remain. There are higher privacy expectations and location-based functions that need to be carefully managed. Monitoring leaderboards and making sure things are fair across devices and sources of data is an ongoing battle. Economic weakness might put downward pressure on discretionary subscriptions, and major-platform changes — such as app store policy shifts or mobile tracking — may jostle acquisition costs.

What investors will watch as Strava prepares for an IPO

For Strava-style filings, focus on conversion-to-paid signals, churn and cohort longevity, app store billing versus direct billing and average revenue per user. International expansion — with local clubs and events — will be a big lever here, as will the pipeline for M&A in mapping, coaching, events and commerce.

The larger question is durability: Is social fitness a durable behavior or a post-pandemic foible? Early signs suggest it is the former. As running clubs replace first dates and Friday nights out in many young adults’ lives, Strava has crafted itself as the infrastructure of that lifestyle — a social network where progress is tracked not in matches but in miles. If that thesis is true, a listing could convert miles into lasting value.