A Starlink satellite has suffered an on-orbit explosion that created a small debris field in low Earth orbit being tracked by U.S. trackers. SpaceX confirmed an anomaly that broke apart parts of the propulsion system, but most of the main satellite body appears quite sound. Preliminary assessments show there is no threat to crewed spaceflight missions, and the spacecraft will reenter within weeks and burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.

What Happened in Orbit During the Starlink Anomaly

Company officials said the failure was a localized fragmentation of part of the satellite’s propulsion tank, a mode that has historically produced low-velocity debris compared to high-energy breakups. The majority of the satellite bus remained in a stable orbit, aiding tracking, and is expected to eventually decay under controlled conditions as a result of natural atmospheric drag. SpaceX said engineers are investigating the root cause and pushing out software protection to the fleet to minimize the possibility of a recurrence.

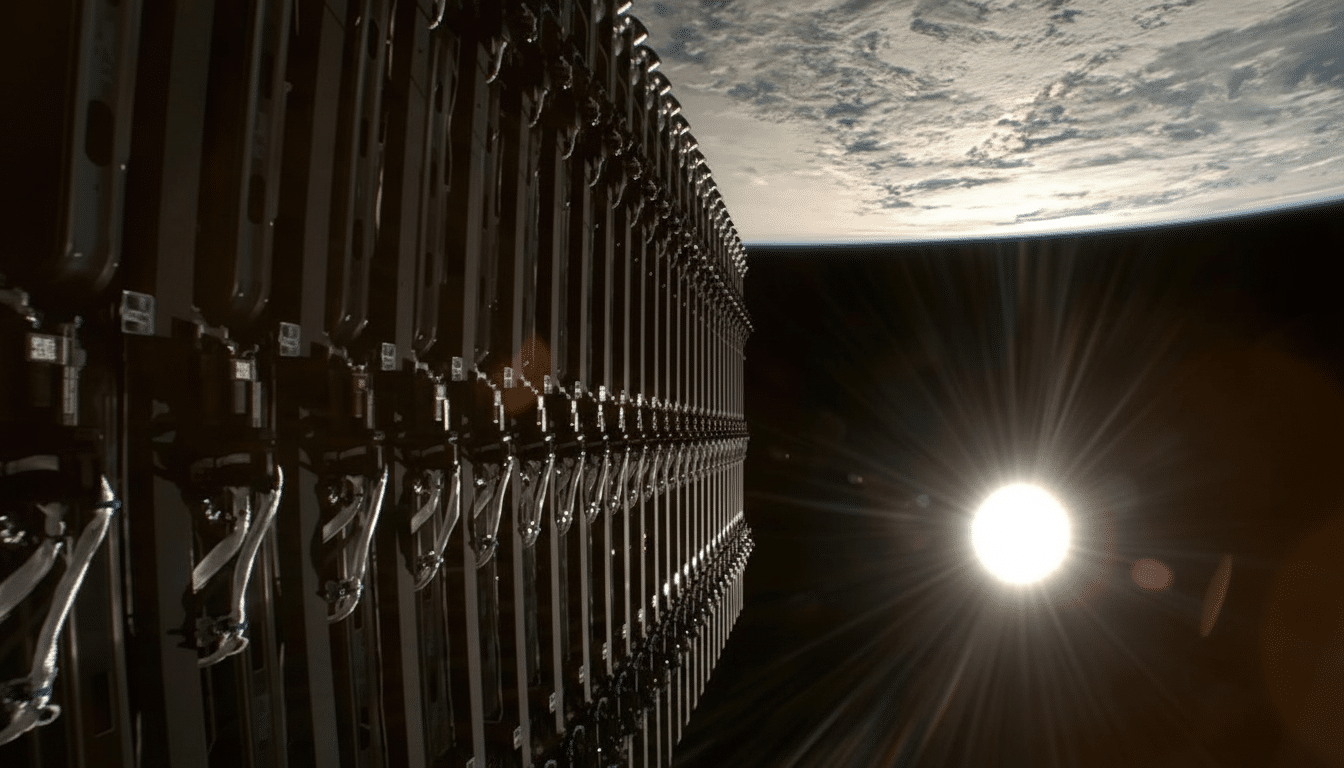

Starlink satellites orbit comparatively close to Earth compared with older communications spacecraft, shortening the lifetimes of debris in that region. That design calculation is a crucial mitigation feature: lower orbits are draggier, and they speed reentry for smaller fragments that can’t hold altitude.

Debris Risk and How Space Agencies Are Tracking It

The U.S. Space Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron, as well as commercial trackers like LeoLabs and analysts at CelesTrak, track pieces big enough to reflect radar or optical signatures. Those teams project orbits and screen them for conjunctions with functioning satellites and the International Space Station. Preliminary signs indicate this debris field is low density and spread out, reducing the chances of any imminent collision risks.

Most debris in low Earth orbit is untracked millimeter-to-centimeter material — record-keeping too fine for routine cataloging but fast enough to wreck hardware. Slight as well as violent fragmentation events are considered to be significant, since further collisions involving the fragments can enhance their collision probabilities. NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office and the European Space Agency’s Space Debris Office have long noted that cumulative small breakups, not just headline-grabbing collisions, empower the background risk environment.

The latest incident comes after a close approach earlier this month between a Starlink satellite and a satellite owned by China’s CAS Space. It is an example of how busy Earth’s orbit has become, with frequent planning needed to ensure that satellites are not at risk of colliding as they soar overhead at high speeds.

But while the vast majority of close encounters end uneventfully due to automated conflict-checking and an operator-to-operator warning system, each one creates more work for controllers and increases fuel burn for avoidance.

Why the Starlink Scale Ramps Up the Stakes

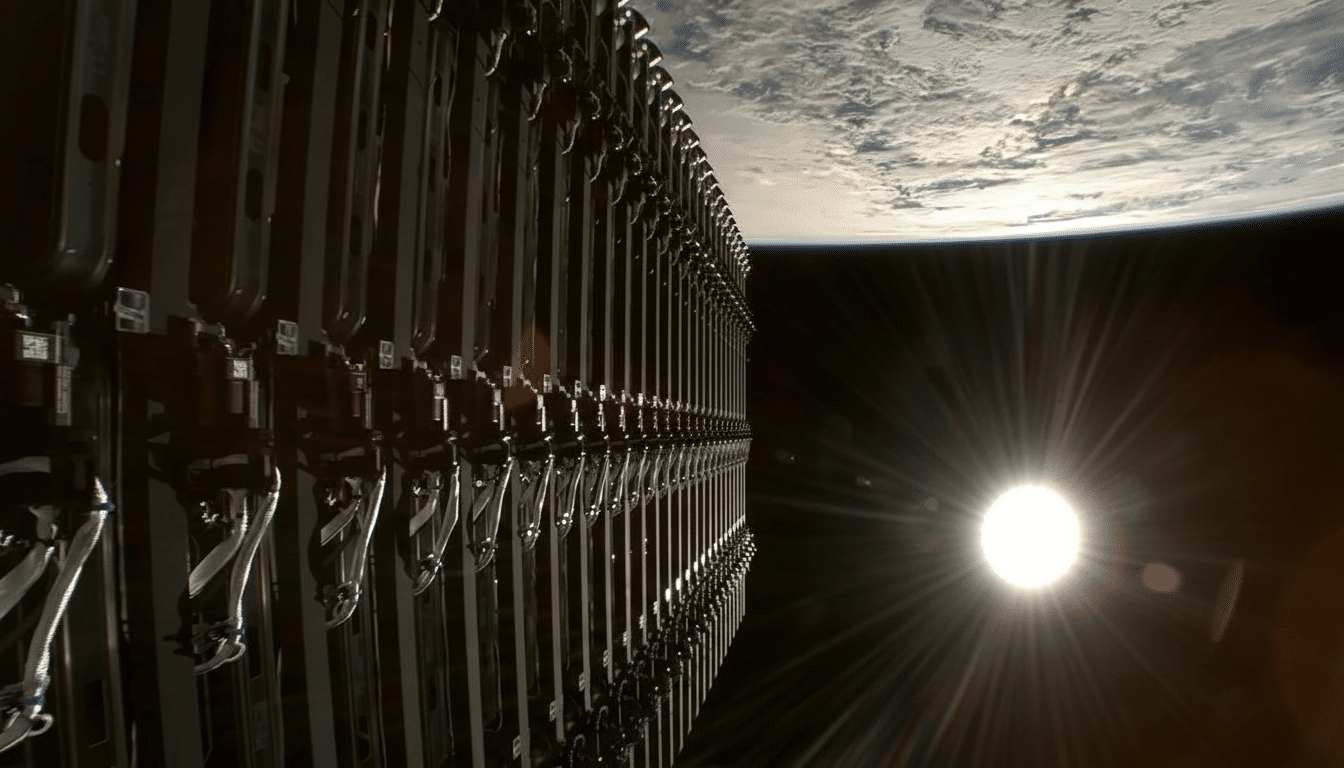

SpaceX has already put up more than 10,000 Starlink satellites, with thousands in orbital service giving broadband services to paying customers around the globe. That scale brings advantages — resilience, coverage and redundancy — but it also amplifies stewardship responsibilities. An event from one satellite is small, but when spread across hundreds and thousands of satellites as in a megaconstellation, even these low failure rates mean consistently dealing with anomalies.

Regulators have tightened expectations. The Federal Communications Commission now mandates that most low Earth orbit satellites be deorbited within five years of the end of their missions, instead of using the traditional guideline of 25 years. Operating shells of the Starlink satellites are meant to deorbit naturally or by actively burning to shorten their orbital life. Passivation — venting remaining propellants into space and discharging batteries — has become a standard end-of-life step to prevent excess force from causing an explosion, and investigators will review the possibility of residual energy or component failure in this case.

Analysts with the Secure World Foundation and academic space traffic researchers often stress transparency: timely updates for the public, counts of fragments when possible and notification of any planned avoidance maneuvers allow other operators to refine their own assessments of risk. SpaceX’s commitment to install defensive software, and share the results, will be closely watched by peers and regulators.

Anticipated Reentry Timeline and SpaceX’s Next Steps

Starlink-level fragments usually come down in periods of days to months (size, mass and solar activity bloat Earth’s atmosphere, dragging more) depending on their size. All but a handful of fragments should fully ablate on reentry — NASA’s casualty risk threshold for uncontrolled reentries is 0.01%, and small LEO spacecraft typically come in below that level. The operators will keep an eye on the catalog for any anomalies that linger above what’s expected.

For the moment, the debris field is modest and routine conjunction screening can contain risks. The larger question remains the same: responsible end-of-life disposal, strong passivation and good anomaly reporting are the best bulwark against small events seeding out into the long-term debris environment. With so many more satellites being launched, today’s rapid response and transparency aren’t just good practice. They are the key to keeping low Earth orbit usable for everyone.