Spoor, the Oslo-based startup using computer vision to make sure birds can fly safely around wind turbines, is attracting a rush of international interest as its technology demonstrates it can scale. Now with deployments on three continents and engagements comprising more than 20 of the world’s largest energy companies, Spoor is transitioning from a pilot curiosity to essential infrastructure for wildlife compliance and turbine optimization.

The momentum comes amid increased scrutiny of the impact on birds from regulators and investors. Spoor’s most recent round of venture funding, an €8 million Series A, led by SET Ventures with participation from Ørsted Ventures and Superorganism, as well as undisclosed strategic investors, is further evidence that the industry is coming around to the idea that monitoring — proper, automated monitoring — will be necessary for wind development and operations.

AI Wildlife Monitoring Becomes Mainstream

Wind developers have long depended on human surveys, spotters with binoculars, and post-construction carcass searches to gauge the number of birds colliding with their turbines. That is an expensive, piecemeal approach that is also frequently contested. Regulators are raising the bar: In Europe, enforcement under the Birds and Habitats Directives has ratcheted up — a major French case this year stopped turbines over avian impact, with hundreds of millions in penalties. Similar pressures are being brought to bear elsewhere by statutes such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act in the U.S.

Wind capacity is also growing at historically high rates. In the Global Wind Energy Council’s view, there will be swift multifold increases over the years as markets rush to deliver for climate goals. However, that growth makes standardized, verifiable monitoring essential — not just to keep developers honest and accountable, but also to help design more intelligent curtailment strategies that minimize both wildlife harm and lost generation.

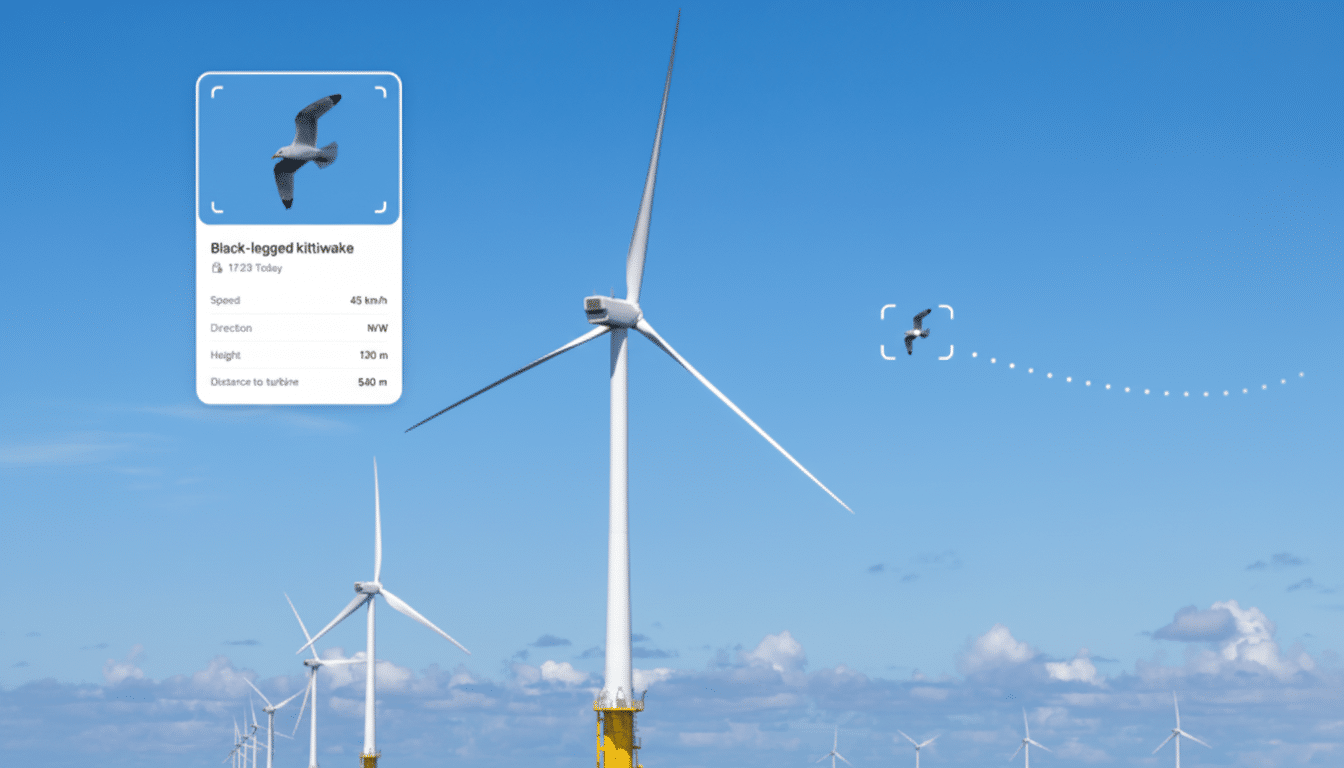

How Spoor’s System Works to Protect Birds Near Wind Farms

Spoor’s software hooks up to off-the-shelf, high-resolution cameras stationed in and around wind sites. Its AI models can detect and track birds within a 1.55-mile radius — more than twice the distance, 0.62 miles, that the company reported during its seed-stage work — and classify targets in ways suitable for species-level assessments. As the training data set has expanded, identification precision now reaches about 96%, with input from an in-house ornithologist as the company expands to new regions and types of birds.

For operators, the payoff is actionable risk analytics: real-time dashboards displaying flight paths and densities; historical heat maps of migration corridors; and alerts indicating areas where a sensitive species likely will be found. Such intelligence can include tactical steps — such as slowing or stopping rotors at times of greatest migration — and strategic ones on where to put turbines to avoid high-risk routes entirely.

There is reason to believe that a targeted approach like this can achieve a significant reduction in harm. Studies compiled by the Renewable Energy Wildlife Institute indicate that curtailment plans can greatly reduce bat fatalities, and data-driven methods are increasingly used to protect birds as well. The virtue of AI monitoring is precision — narrowing the curtailment window to just the riskiest hours and conditions, minimizing revenue loss while maximizing conservation outcomes.

Beyond wind energy: new applications for Spoor’s wildlife AI

Interest is spreading outside wind. The idea is to keep watch over both planned and makeshift airfields, from the nation’s largest airports (which deal with thousands of reported wildlife strikes every year, according to the Federal Aviation Administration’s Wildlife Strike Database) to smaller airstrips, in search of incoming flocks. Similar techniques to control interactions with seabirds in sensitive coastal areas are being considered at aquaculture sites.

Spoor is also testing out its detection stack on other flying fauna. A collaboration with Rio Tinto is monitoring bats, a growing problem for mines and renewable energy companies. The software can also identify the signatures of drone-like objects — “plastic birds,” as company leadership jokes — although Spoor says it’s not pivoting toward security or counter-UAS use cases just yet.

Adoption signals and early results from global deployments

The company’s footprint with marquee energy companies marks a move away from ad hoc tryouts toward sweeping, programmatic rollouts. Developers point to three drivers: de-risking permits under the stricter environmental reviews, streamlining post-construction monitoring requirements, and optimizing curtailment to protect both wildlife and revenue.

Teams on the ground say automated tracking supplements observations that can be lost due to weather, at night, and over far-ranging territory where human surveys become impossible. For operations that are close to protected habitats, species identification adds another crucial layer, where the cost of getting it wrong can include a shutdown at gunpoint, reputational damage, and litigation.

Funds to scale and standardize AI wildlife monitoring

The infusion of new capital will assist in accelerated deployments, an expanded species database, and product features that also comply with new regulatory standards for monitoring wildlife. The mission, succinctly framed by Spoor’s leadership: helping industry and nature coexist, by turning avian risk into a measurable, manageable variable rather than an unpredictable liability.

Next stages include proving to the sector whether AI-native monitoring can be a new norm for permitting and operations across wind portfolios. As enforcement tightens and clean energy speeds up, the calculus is shifting. Assuming Spoor’s accuracy improvements and cost profile remain on track, automated avian intelligence could be just as much a matter of fact at wind sites as SCADA data — and a critical enabler in building more turbines where they belong.