Talk of moving artificial intelligence off Earth has gone from sci‑fi daydream to boardroom agenda. SpaceX has sought permission for solar‑powered compute in orbit, Google is preparing Project Suncatcher prototypes, and startup filings now read like constellation manifestos. Yet the early math is unforgiving: even with rapid innovation, the economics of orbital AI remain punishing.

Launch And Logistics Dominate The Orbital AI Bill

Getting mass to orbit is still the price setter. Falcon 9 class rides cost roughly $3,600 per kilogram today. Suncatcher’s technical brief argues orbital AI becomes compelling closer to $200/kg—an 18x drop more likely in the 2030s than next year. Starship is designed to chase that curve, but until flight rate, reliability, and reusability are proven at scale, the sticker price to customers will reflect scarcity, not aspiration.

Even if Starship hits its targets, market dynamics matter. Analysts at Rational Futures note launch providers rarely undercut rivals by more than necessary; if New Glenn lists near $70 million per mission, expect competitive pricing gravity. Meanwhile, global launch cadence cannot yet support tens of thousands—let alone millions—of AI satellites. As one hyperscale cloud chief put it recently, there simply aren’t enough rockets.

The Real Price Of Power In Space-Based Compute

On Earth, power is a line item. In orbit, power is the whole business. A 2025 Suncatcher analysis compares energy on a kW‑year basis: terrestrial data centers pay roughly $570–$3,000 per kW‑year depending on location and efficiency; delivering the same energy via satellites—once you account for build, launch, and maintenance—lands near $14,700 per kW‑year. That gap must close for orbital compute to pencil out.

Space offers an advantage: sun exposure can exceed 90% of each day, and panels operate above weather and atmosphere. But panel choice is a brutal trade. Radiation‑hard gallium‑arsenide arrays are robust and expensive; silicon is cheaper but degrades faster under cosmic rays. Several suppliers expect about five‑year lifetimes for silicon‑based power stacks in LEO, compressing payback windows and increasing replacement cadence.

Heat Rejection Is Not Free In High-Density Orbital AI

No atmosphere means no convection. High‑density GPUs must dump heat through large radiators, heat pipes, and phase‑change systems, all of which add surface area, mass, and complexity. Planet Labs engineers collaborating on Suncatcher prototypes have flagged thermal as a primary bottleneck, not a footnote—especially as power density rises.

Radiation is the twin headache. Bit‑flips from high‑energy particles corrupt memory and can derail long training runs. Mitigation—shielding, rad‑tolerant chips, redundancy—costs money and kilograms. Google has blasted its TPUs with particle beams to characterize failures, and SpaceX has reportedly acquired accelerator hardware to do the same. The fixes exist; they just aren’t cheap.

Bandwidth Bottlenecks Shape The Workloads

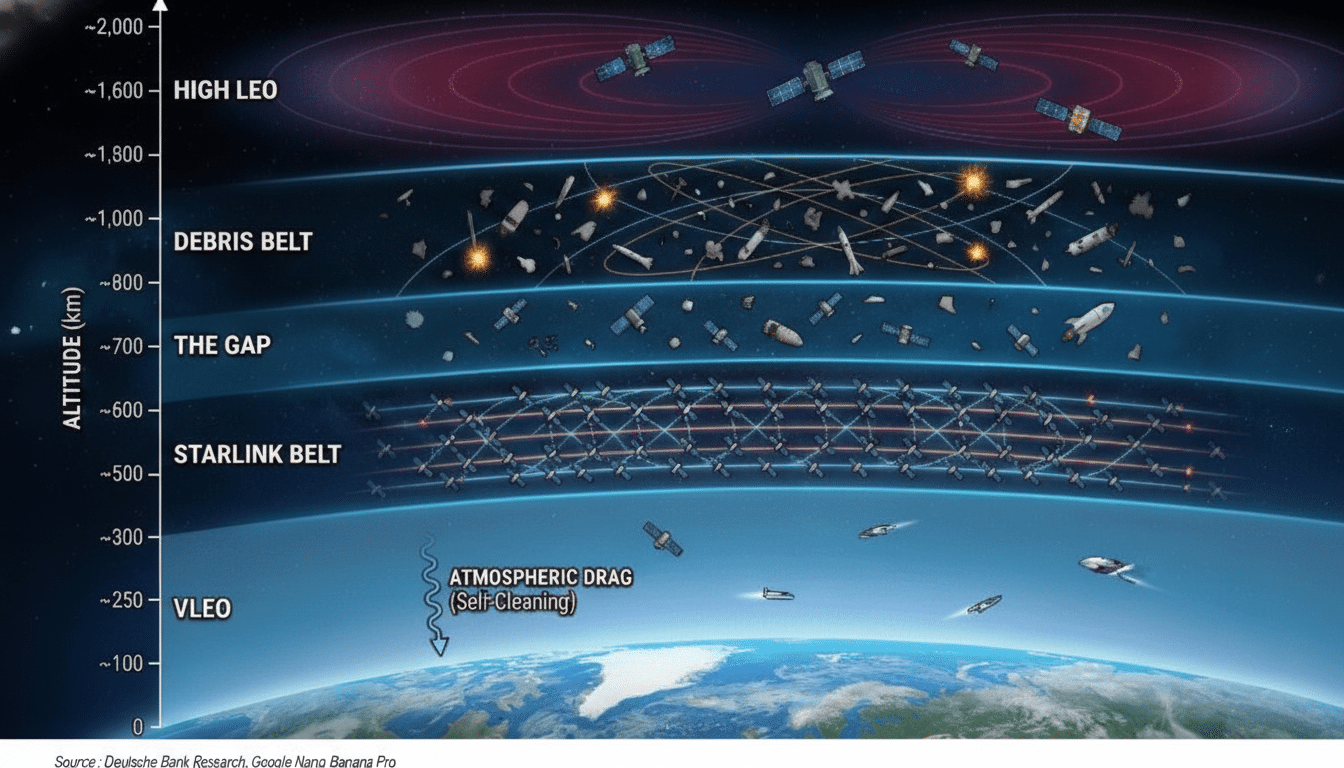

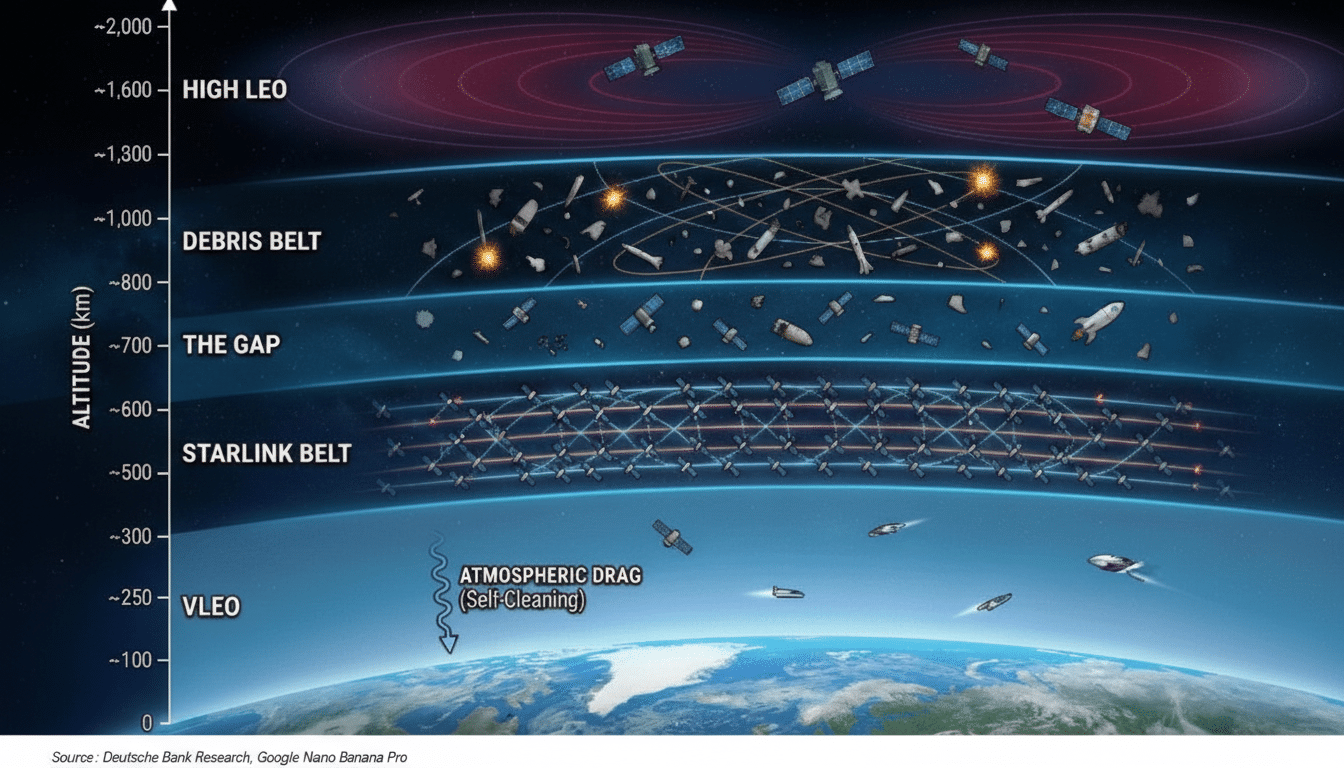

Training frontier models ties thousands of accelerators together over fabric links in the hundreds of Gbps per node. Off‑the‑shelf inter‑satellite laser links peak near 100 Gbps today. That delta forces architects into exotic formations—Suncatcher’s concept clusters 81 satellites in tight formation to use shorter‑range, higher‑throughput transceivers—introducing station‑keeping, collision avoidance, and debris‑response costs.

Inference is the near‑term fit. Dozens of GPUs can serve chat, vision, or speech workloads without ultra‑tight coupling, and LEO latency can rival or beat long terrestrial backhaul for globally distributed users. Expect first revenue to come from inference nodes colocated with laser backbones, not sprawling training superclusters.

Manufacturing Scale Or Bust For Space AI Hardware

Hardware economics hinge on throughput. Starlink proved satellites can be built on assembly lines, and orbital AI proponents are betting that higher‑power buses can be mass‑produced at a fraction of today’s costs. Even so, an engineering analysis by Andrew McCalip estimates a 1 GW orbital build could cost about $42.4 billion—roughly 3x a ground equivalent—before operations. Bringing that down demands new supply chains for space‑grade power electronics, radiators, optics, and lasercom at automotive scale.

Capital is another limiter. Between launch, spacecraft, and on‑orbit spares, a credible constellation ties up tens of billions before breakeven. Insurance, debris mitigation, spectrum coordination, and in‑space servicing add non‑trivial operating expenses that terrestrial data centers avoid.

What Could Flip The Equation For Viable Orbital AI

Three catalysts would change the calculus: sub‑$200/kg fully reusable launch with high cadence; cheap, radiation‑tolerant solar and thermal systems with 7–10 year lifetimes; and Tbps‑class optical crosslinks. On‑orbit refueling and servicing would further extend asset life. If those arrive as grid power prices and water constraints rise—trends flagged by the International Energy Agency and Uptime Institute—orbital AI becomes a hedge against terrestrial bottlenecks.

Meanwhile, the market isn’t waiting. xAI insiders have wagered that 1% of global compute lives in space by 2028. Google has flight tests queued, and venture‑backed entrants have filed for constellations numbering in the tens of thousands. SpaceX itself can arbitrage between ground and orbit as permitting or power limits pinch new campuses: a FLOP is a FLOP, but not at the same price.

The bottom line is clear. Orbital AI will ship first where physics and cash flows agree—inference nodes that monetize immediately, not galaxy‑scale trainers. Until launch, power, thermal, and networking costs fall by an order of magnitude, the economics remain as unforgiving as space itself.