Russia is developing a homegrown low-Earth-orbit (!) broadband constellation, and its depiction looks eerily familiar to SpaceX’s Starlink — flat user terminals, Ku/Ka-band links and, importantly, given this writing project, satellite-to-satellite lasers. The initiative is being led by the company Bureau 1440, which was established with the backing of mobile operator MegaFon and promises to offer gigabit-class service beamed from hundreds of kilometers above Earth.

State media has promoted the system as a leap past Starlink with seamless laser crosslinks. The marketing is bold. The engineering, though, hews to a playbook SpaceX helped pioneer: a thick ring of LEO satellites laced together by lasers that route data in space and cut the need for ground-based way stations.

What Russia Is Building for Its LEO Broadband Network

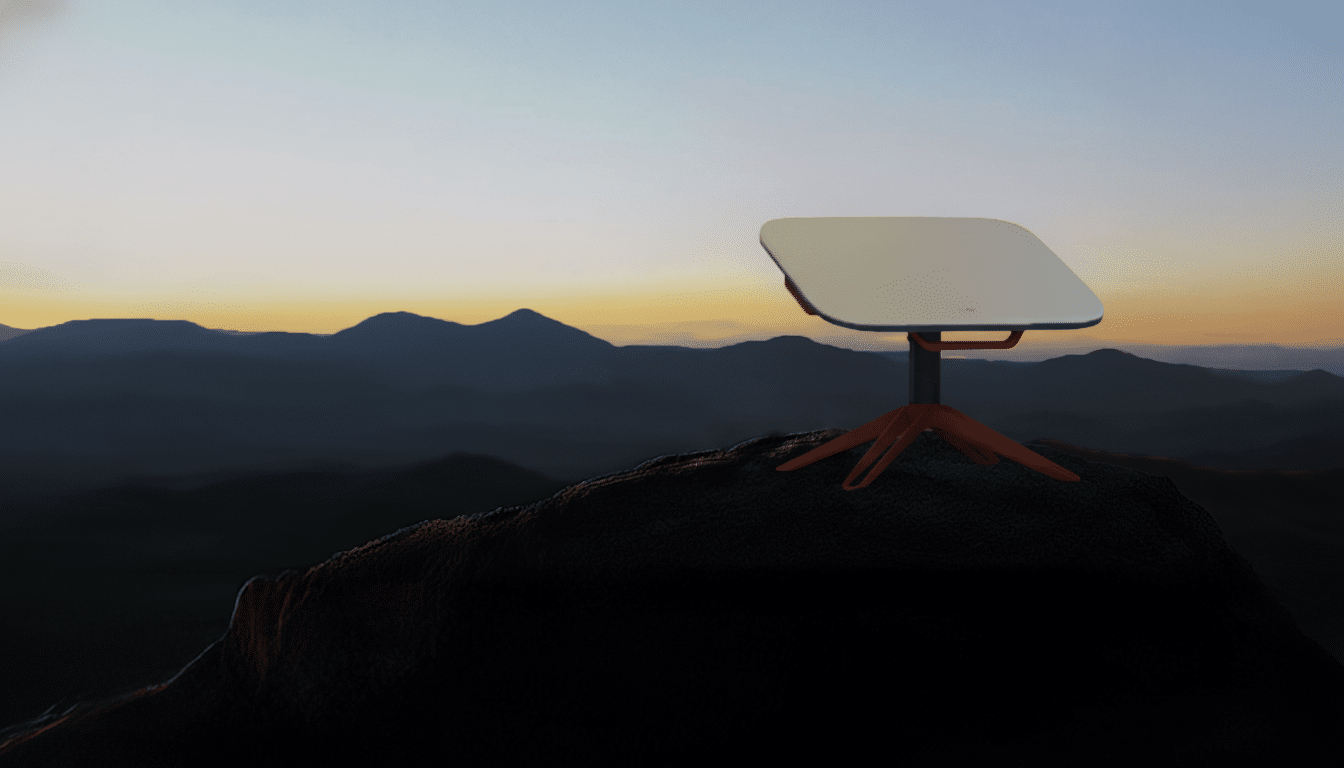

According to company materials and public statements from Russian officials, Bureau 1440 intends a constellation in low-Earth orbit at about 800 kilometers. That is higher than Starlink’s primary shells, which orbit at about 550 kilometers. The system aims to deliver up to 1 Gbps downlink service to users via small, electronically steered antennas — a design choice that emulates the low-profile phased-array dishes SpaceX has developed for home and mobile reception from its own Starlink system.

Higher orbits increase the footprint for each satellite, increasing coverage (at a cost of slightly higher path loss and slightly more latency). For rural broadband, mobile backhaul and polar routes, that trade-off might be fine — so long as the rest of the architecture is able to make up for it with smart beamforming and liberal re-use of spectrum.

The Laser Link Play and Optical Crosslink Ambitions

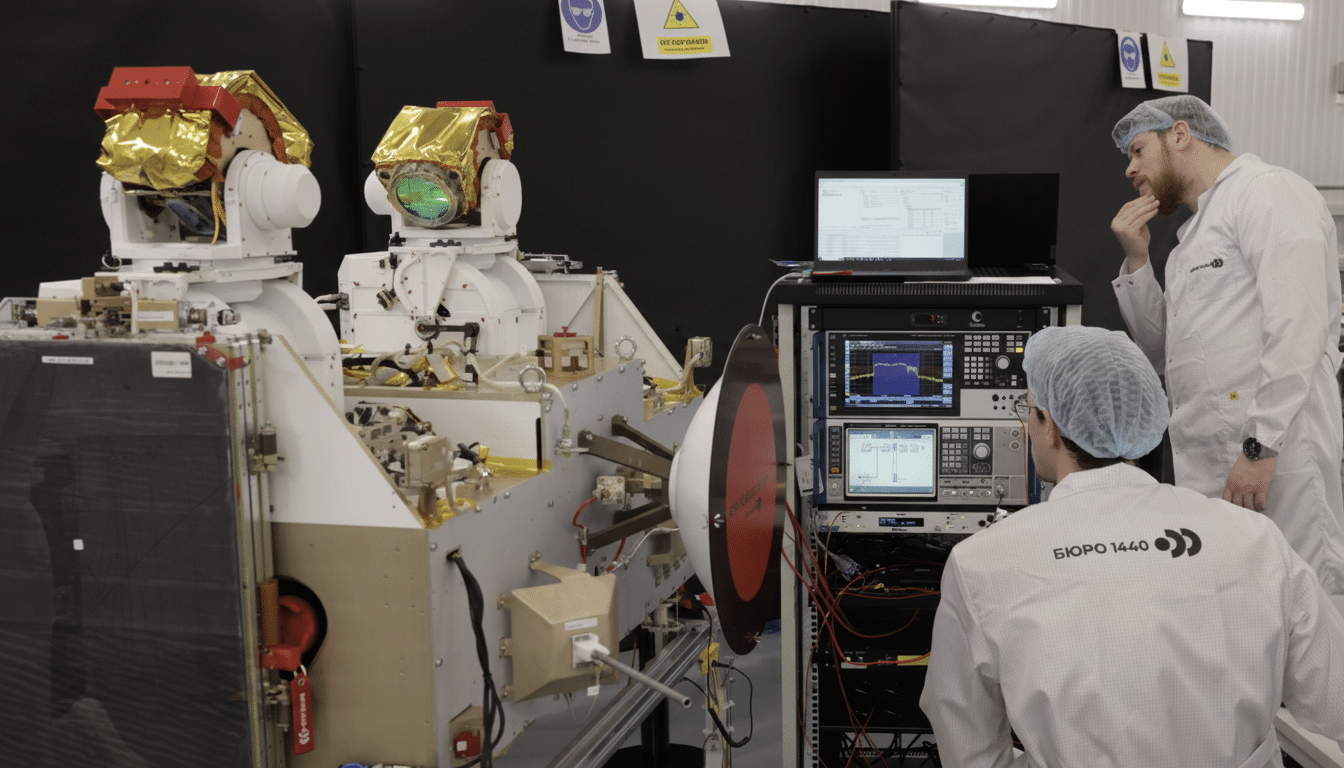

Optical inter-satellite links are the headliner. Bureau 1440 says it will employ in-house laser terminals for satellites to relay data between one another above the planet’s atmosphere. SpaceX brought this approach into the mainstream: Its newer Starlink satellites include laser crosslinks rated by the company at about 100 Gbps per link, so that traffic can hop around the mesh without going through the ground — a critical feature for oceans and other low-connection regions.

The lasers are also no mere add-on option. Pointing at a moving platform hundreds of kilometers away requires sub-milliradian precision in pointing, tight thermal control and radiation-hardened optoelectronics. European suppliers, including Tesat, have already flown such terminals; and China and the United States have proven military-grade optical networks in orbit. If Russia really does standardize and build these terminals at scale in-country, that’s a big industrial win — just one that needs to be demonstrated on-orbit.

Altitude Trade-Offs and Constellation Math

~800 kilometers has consequences in that choice. Coverage is better the higher it gets, and fewer satellites are required for global reach. That would bolster the official line that “hundreds” could do just fine at first, with expansion into the low thousands as capacity needs grow. But physics imposes a cost: compared with ~550 km, free-space path loss is 3.3 dB higher at 800 kilometers — that is, user terminals require slightly more antenna gain and/or satellites must radiate more power to meet the same link margin.

The latencies added for last-mile access aren’t huge — just a few extra milliseconds in the user-satellite hop — but adding to capacity is how total network performance will be determined. Coverage is straightforward; capacity isn’t. The fewer satellites, the fewer the cells across dense cities and less spectrum reuse. Lasers move bits around the sky, but they don’t make any more radio spectrum available on the ground. To be competitive, Bureau 1440 will require aggressive beam hopping, high-throughput payloads mimicking the best LEO systems and tight frequency reuse.

Supply Chain, Spectrum, and Regulatory Paperwork

The big problem is procurement of physics. They point, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies and European sanctions monitors concur, to persistent limitations on Russia’s access to radiation-hardened electronics, high-power gallium nitride RF ingredients, precision optical assemblies and phased-array chipsets — all of which are needed for laser-linked LEO broadband. “Whatever you want to do,” said a seasoned trade veteran. “You want to build products here in the U.S.? A robust domestic substitute or third-country sourcing would support that wish list as fait accompli.”

Regulatory steps are equally unforgiving. Any global broadband constellation has to secure International Telecommunication Union filings, coordinate with Ku/Ka-band spectrum holders to avoid interference and negotiate landing rights in nation after nation. Russia’s wider Skif program has ITU filings attached as part of its “Sfera” plan, but Bureau 1440’s specific filings, gateway locations and market access will determine whether the network serves national needs or is a truly international challenger.

A Crowd in Low Earth Orbit: Competitors in LEO

Bureau 1440 slips into a crowded ring of heavyweights anyone else might like to enter. SpaceX has thousands of satellites in orbit and a well-established laser grid that serves maritime, aviation and remote enterprise services today. Amazon’s Project Kuiper is progressing from a project toward early service. Europe is building IRIS² as a sovereign secure communications network. China’s project, called the Guowang constellation, is designed to operate at national and commercial scale. Eutelsat OneWeb operates a higher-altitude network focused on enterprise and government backhaul, relying more heavily on ground gateways than optical crosslinks.

Bottom Line: Execution Will Decide Competitiveness

Russia’s LEO broadband blueprint steals the necessary right ideas: flat phased-array user terminals, laser-linked satellites, and an altitude that sacrifices some performance for coverage. That makes it nostalgic rather than revolutionary — and not in a bad way. The differentiating factors will be execution: flight-proven optical terminals, cost-effective user equipment, continued ramp toward mass production, spectrum coordination that is a cast-iron guarantee, and cyber-jamming and sanction resilience.

Should Bureau 1440 pull that off, the lasers won’t just be a marketing gimmick — they’ll be the foundation of a competitive Starlink alternative.

If not, the constellation is in danger of joining a growing list of LEO paper projects eclipsed by rivals already operating at scale.