A star in Monoceros briefly pulled off one of astronomy’s best disappearing acts, fading almost from view for months before returning to normal. Now researchers report a striking explanation: the light of ASASSN-24fw was nearly blotted out by a giant ring system encircling a hidden companion, likely a brown dwarf or super-Jupiter, according to a study in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The event ranks among the longest and deepest dimmings ever recorded. At its faintest, the star’s brightness dropped by about 97%, a level of obscuration far beyond ordinary stellar variability and well into eclipse territory. The culprit’s rings, far larger and thicker than those around Saturn, provided an enormous moving screen between the star and Earth.

A Months-Long Eclipse With An Unusual Culprit

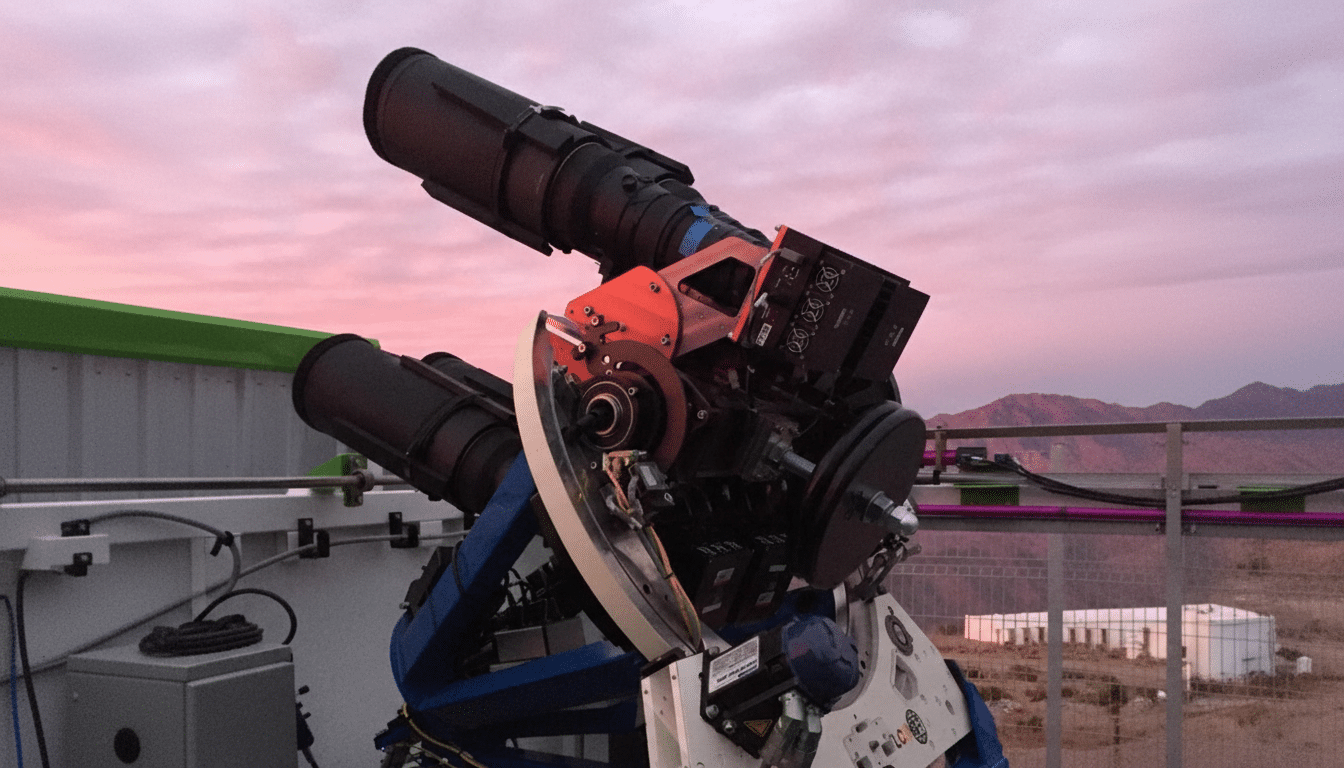

ASASSN-24fw, a star roughly twice the size of the Sun and about 3,200 light-years away, was flagged by the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae—an automated network that routinely catches transient changes in the sky. Instead of a quick fade and rebound lasting days or weeks, the star dimmed gradually and stayed suppressed for nearly 200 days before brightening again.

Such long, smooth fades are rare because they demand an almost perfect alignment of orbital planes. The research team, led by Sarang Shah of the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, tested multiple models against the light curve and its subtle color changes. The best fit points to a substellar companion shrouded in a colossal, multi-ring structure that drifted in front of the star like a vast, layered veil.

By analyzing how the starlight dimmed and recovered—its timing, depth, and wavelength-dependent behavior—the team inferred that the occulting object has a mass exceeding three Jupiters, placing it in the realm of a massive planet or brown dwarf. Either way, it is too small to be a star and too hefty to resemble typical exoplanets.

A Giant Ring System Far Larger Than Planets

The favored scenario involves a brown dwarf surrounded by rings that mirror Saturn’s layered architecture but scale up to extraordinary dimensions. The rings are estimated to extend roughly 15.8 million miles from the companion—about half the distance between the Sun and Mercury—ample real estate to carve deep, sustained notches in a star’s output when seen edge-on from Earth.

The modeling indicates the outer rings are diffuse, explaining the slow onset, while inner regions are denser and more opaque, driving the dramatic light loss near mid-transit. When the ringed companion moved on, the star’s full beam returned, just as a clean egress would predict.

Intriguingly, the data hint that ASASSN-24fw may host leftover debris—possibly from ancient collisions—closer to the star than expected for a system believed to be older than a billion years. The team also reports a nearby red dwarf companion, adding another piece to a complex celestial puzzle that likely includes multiple bodies and reservoirs of dust.

How It Fits Into Other Disappearing-Star Mysteries

Astrophysicists have seen similarly bewildering dimmings before, but few with this combination of duration and depth. The famed “Tabby’s Star” showed irregular dips up to about 20%, later tied to dust. Epsilon Aurigae undergoes a years-long eclipse every few decades due to a massive, dusty disk. And in 2012, VVV-WIT-08 nearly vanished behind an opaque screen. ASASSN-24fw adds a compelling case to the short list suggesting giant ring systems around substellar objects can masquerade as disappearing stars.

Another precedent is J1407, where a complex, multi-week dimming has been interpreted as a possible super-Saturn ring system. ASASSN-24fw’s event is longer and cleaner, offering a rarer laboratory to probe ring structure, particle sizes, and the dynamical choreography that maintains such expansive disks.

What Astronomers Will Look For and Study Next

To tighten constraints on the ringed companion’s mass and architecture, the team plans follow-up spectroscopy and high-contrast imaging with flagship facilities, including the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope. Detailed spectra can reveal the host star’s temperature, chemical makeup, and age more precisely, while infrared observations may detect the thermal glow of dust and refine ring particle properties.

Because the likely orbital period is decades long, the next eclipse may not recur for about 42 years. That makes archival searches and coordinated monitoring critical. Surveys such as the Zwicky Transient Facility, Gaia, and the forthcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory could catch precursors—subtle dips or asymmetries—offering early warnings and a chance to mobilize rapid, multi-wavelength campaigns.

For now, the verdict is clear: this star didn’t die, dim, or flare on its own. It was hidden by a colossal ringed world drifting across our line of sight—a reminder that planetary systems beyond our own can build structures on scales that challenge intuition and reward patience.