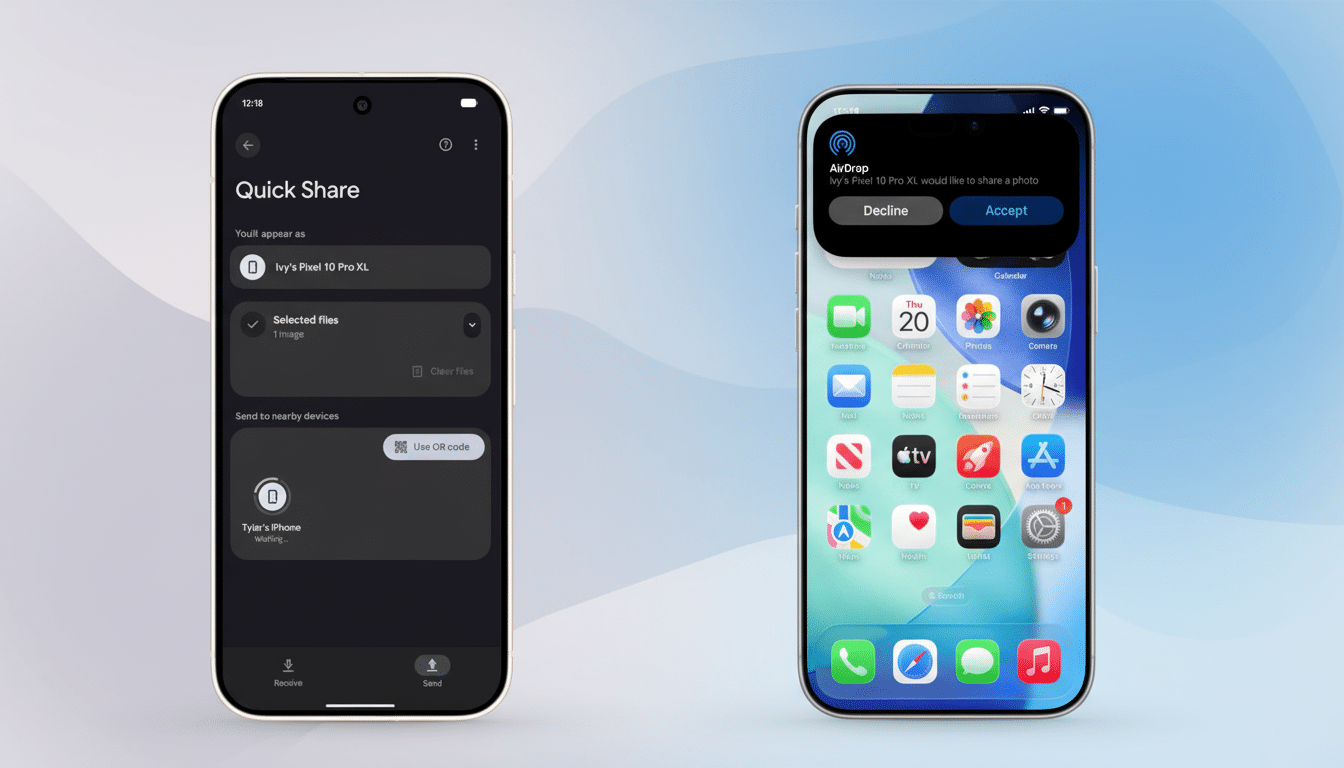

I just beamed a stack of photos and a 4K clip from a Google Pixel to an iPhone, with AirDrop, and it was such a simple process that I had to check twice what I’d been tapping.

No cables, no cloud, no strange workarounds—just Quick Share on the Pixel, AirDrop on the iPhone, and a pop-up that was as much a feeling that the ecosystems had shaken hands.

- Hands-on with cross-platform AirDrop between Pixel and iPhone

- What’s Probably Going on Behind the Scenes

- The caveats to know before sharing between Pixel and iPhone

- Why this is more than just a novelty for everyday users

- What’s next for Quick Share and broader Android support

- The moment it clicked: when sharing actually felt seamless

Hands-on with cross-platform AirDrop between Pixel and iPhone

The setup is refreshingly light. Update your Pixel to the latest Quick Share build, make sure the iPhone’s AirDrop is set to Everyone (or, at least, Everyone for 10 Minutes), and away you go. I chose the iPhone from the Pixel’s share sheet, and within a heartbeat an AirDrop card popped up on the Apple side. Tap Accept, and the file plops down where you’d expect it to—Photos for images and videos, Files for documents—with no detours.

With, again, very little hesitation in repeated side-by-side tests, single photos zipped across; a short 4K clip arrived in seconds; and even chunky RAW files cleared swiftly enough to make the process blur by in day-to-day use.

Transfers to a MacBook and a Mac mini worked similarly. A few times, the transfer to the Mac timed out (this happens to me even with AirDrop between Apple products), so the hiccup didn’t seem too out of character.

What’s Probably Going on Behind the Scenes

Getting a Pixel to talk AirDrop is no small thing. The actual payload for an AirDrop discovery takes place over Apple Wireless Direct Link (AWDL)—a proprietary Wi‑Fi–based peer‑to‑peer protocol, though Apple’s devices have this feature built in. The Secure Mobile Networking Lab at TU Darmstadt researchers published years ago on AWDL’s behavior, and they even published open-source tools that demonstrated that non‑Apple devices could, in fact, talk to AirDrop while it was in Everyone mode. That foundation suggested this moment was conceivable; Google’s polish makes it seem natural.

The tell is the Everyone requirement. When AirDrop is configured as Contacts Only, there are checks for Apple IDs and certificates that act to gate the session. And without Apple’s participation, a Pixel doesn’t make it through that identity handshake. Flip to Everyone (or the safer Everyone for 10 Minutes offering added to discourage unwanted shares), and the door opens—still encrypted, on‑premises but sans contact‑verified handshake. It’s a pragmatic compromise that ensures privacy while allowing interoperability.

The caveats to know before sharing between Pixel and iPhone

There are trade‑offs. The Apple device needs to be configured to accept from Everyone, which makes one extra thing that recipients have to do (since most people lock AirDrop down only to Contacts). Discoverability windows matter as well; the iPhone or Mac has to be awake and in range. And like any peer‑to‑peer radio tech, a busy 5 GHz airspace can affect reliability—hardly ever, but noticeably in an office with lots of competing users.

File formats are handled sensibly. HEIC photos and ProRes clips sent directly from an iPhone hit a Pixel sidecar with all their pixels, too: Android has supported HEIF/HEVC for years; Google Photos opens them just fine. On the other hand, Pixel RAWs as well as high‑bitrate videos fly across to Apple devices without having been transcoded. The goal is not conversion—it’s fidelity and velocity—and on that, the experience feels a lot like same‑ecosystem sharing.

Why this is more than just a novelty for everyday users

Cross‑ecosystem households are the rule, not the exception. According to Google, there are more than 3 billion active Android devices; Apple has said it has over 2 billion active devices across all of its products. iPhones and Pixels, Macs and Windows PCs are often intermingled within families, teams, and classrooms. Quick Share already connected Android to Windows; connecting Pixel to AirDrop is one of the last big missing links in local sharing.

There is also a regulatory current underneath this. (Legislation in the European Union, the Digital Markets Act, is pushing platform owners toward more interoperability when it comes to messaging and discovery.) Apple’s embrace of RCS for iPhone came across as a willingness—with conditions—to ease tension with rival platforms. AirDrop-like feature parity wasn’t committed to by Apple, but what reality we have today indicates that there were never technical barriers so high they could not be climbed.

What’s next for Quick Share and broader Android support

Currently, the best example I can point to is Google’s latest Pixels, where the level of integration is of another product entirely. For this to change daily habits, it needs to scale out across more Android phones—Samsung, OnePlus, Motorola, and beyond—and not fragment this work. Since Google previously unified Nearby Share under the Quick Share brand, a broad rollout seems attainable, but it will come down to consistent performance across chipsets and Wi‑Fi stacks.

Two advantages would make this revolutionary: cross‑platform trust at the contact level (thereby removing the Everyone toggle), and a less ambiguous UX on Apple devices that acknowledges established non‑Apple senders. The former probably necessitates standards work or the buy‑in of Apple; the latter is as much a matter of policy as it is technical.

The moment it clicked: when sharing actually felt seamless

The greatest technology disappears when you use it. To tap Share on a Pixel and see the AirDrop card of an iPhone pop up—instantly, consistently—felt like someone had lowered the walls just enough to do what people have always wanted to do: move a file to the closest device without pondering or stressing. It’s still not perfect, and yet it is already good enough to shift habits. And that’s when the phrase “it felt like magic” ceases to be hyperbole and becomes a commonplace.