In a spectacle that was part hacktivism, part performance art, a security researcher dressed up as the Pink Power Ranger at the Chaos Communication Congress in Germany and proceeded to take down several white supremacist sites while onstage. The hacker, who identified herself as Martha Root, took civic responsibility for bringing down niche platforms designed to serve racist communities and showed how those operations were infiltrated from the inside.

A Theatrical Takedown at Chaos Communication Congress

Root’s live demonstration was part technical postmortem, part public shame-fest. Onstage, she explained how “WhiteDate,” a white supremacist dating site, as well as related sites “WhiteChild” and “WhiteDeal,” were not only ideologically dangerous but also shockingly insecure. After taking the audience through high-level findings, Root triggered deletions that essentially wiped the sites off the map — an unusually public end for communities that generally flourish in secrecy.

Event organizers at the Chaos Computer Club, which hosts the long-running conference, are infamous for provocative talks that push digital rights, social engineering, and platform accountability to their limits. This one was a direct arrow in the tradition of hacktivism: Theatre, high-profile intervention designed to make an example of the sloppiness and the extremists who relied on them.

Inside the operation targeting white supremacist sites

Root’s presentation, and subsequent reporting, show that the campaign started months before with penetration and intelligence gathering. Root employed a chatbot-assumed identity to speak with users on WhiteDate, passively mapping the community’s structure while also evaluating the newfound platform’s technical architecture. From that point, Root was able to reach an insecure backend, which she used as a mere listing of the exposed data and vulnerabilities that are ultimately typical of poorly executed deployments — your misconfigured content management tools, your reused credentials, etc., rather than breaking down exploit-by-exploit.

To document the operation, Root created a searchable public archive of non-sensitive materials that she made available to researchers and journalists, pointedly leaving out passwords, private messages, and emails. The idea, Root said, was to produce a record that could be verified without doing further damage to victims and bystanders.

Why the exposed WhiteDate data matters for users

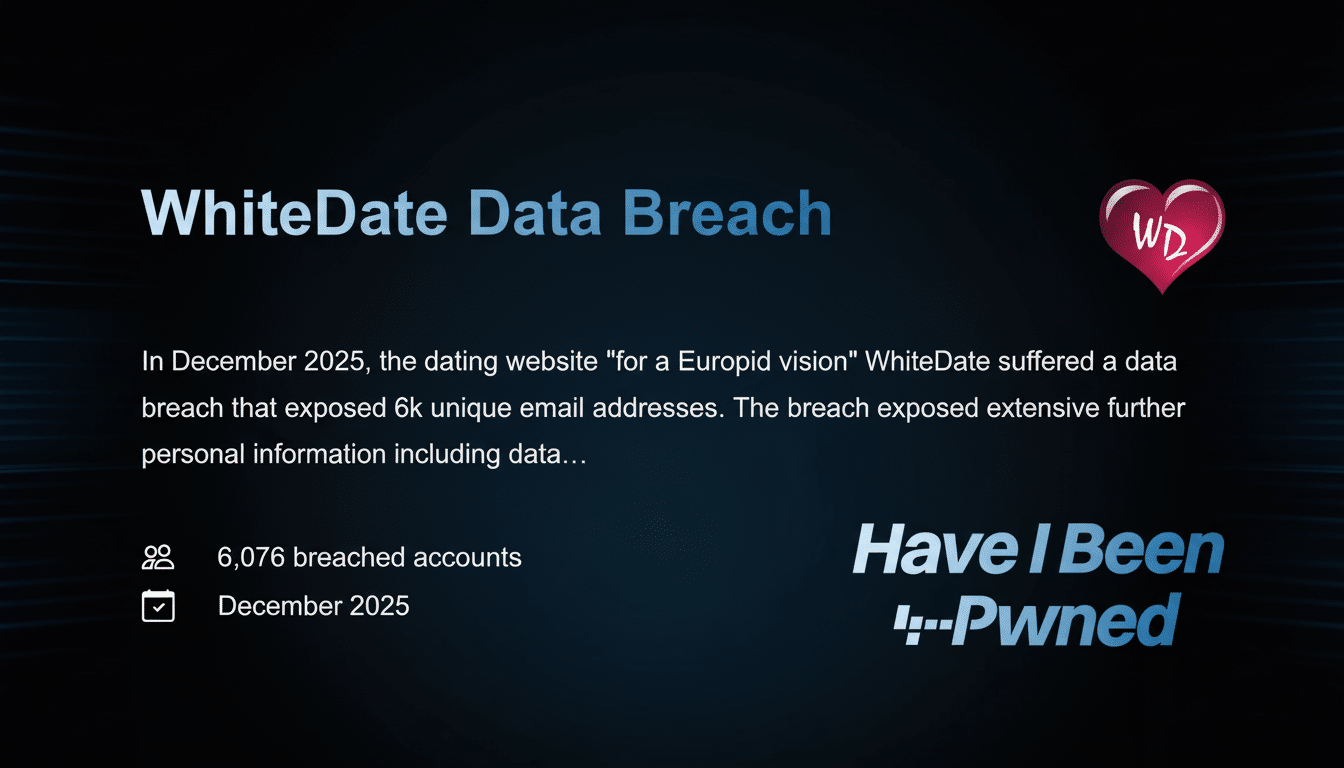

The dump affected more than 6,000 WhiteDate profiles — many images from end users still contained embedded geolocation information. Names, ages, and partner preferences were standard. Some profiles included granular personal details — household plans, income claims, education levels, even astrological signs — that formed a profile soup that had the potential to be weaponized in the hands of harassers or doxxers.

The exposure is listed on Have I Been Pwned, the breach notification service founded by security researcher Troy Hunt, that lets anyone check whether their data was exposed in the breach. As with many fringe platforms, researchers point out that extremist sites tend to have much worse basic security hygiene than mainstream sites do — and WhiteDate fits that profile: poor access controls, user operational security is not great, a scant progression toward data protection.

Data handling and verification to minimize harm

The materials are in the custody of Distributed Denial of Secrets, or D.D.O.S., a nonprofit group that publishes leaked and hacked data, which is providing access to them. That gatekeeping is modeled on practices that have been maintained in earlier dumps of materials that, while they may contain potential public-interest value, also risk causing harm if posted wholesale. These responsible access paths, in turn, permit independent verification without turbocharging harassment campaigns or giving a tailwind to copycat abuse.

Security researchers who reviewed samples said the dataset looks legitimate and has not been faked or manipulated, though no public dump of the data is known to have taken place. How to balance transparency and minimizing harm — or rage interpretation vs. outrage management (particularly when the targets are extremist communities that deliberately attract both scrutiny and notoriety) — is still the square knot in handling leaks.

Legal and ethical fallout from an onstage takedown

The administrator for the removed sites slammed the takedown as “cyberterrorism,” an accusation that hacktivists have heard many times before over work that crosses into unauthorized access or disruption.

Legal specialists say that even when the targets are purveyors of hate, intruding into networks and exfiltrating data can transgress computer misuse laws in the EU and beyond. Conferences generally frown upon hacking third parties in real time; Root’s demo, while not normal, underscores how hacktivism often pits a public-interest argument against legal lines in the sand.

From an ethical perspective, Root’s team justified the operation as a harm-reduction effort. Extremist communities are markets for radicalization and recruitment; demolishing their infrastructure disrupts those pipelines and lays bare the lie of operational competence. Critics argue that such steps can push groups to harder-to-trace platforms and complicate the task of law enforcement investigations. Both dynamics have precedent.

The Larger Context for Extremist Platforms

The episode underscores a larger truth: many hate-filled platforms are run by shoestring operations using off-the-shelf and easily accessible online software, managing to stay online despite pressure from authorities only because they receive little scrutiny from the companies that host them or from researchers who could make their work more difficult. Groups that monitor extremism, like the Anti-Defamation League, have repeatedly shown how, when they are exposed or deplatformed, such groups move from niche forums to encrypted channels and low-budget sites. Root’s takedown may be disruptive in the short run, but what matters now is whether copycat communities again spring up and, if they do, whether they prove to possess better operational security — or whether a few months of attention from Lake Worth deter new diaspora operators.

For now, Root’s Pink Power Ranger moment brought a fleeting glimpse of hacktivism in action — an investigator dressed as a stage act, and some racist sites turned into a case study on bad security and public accountability. Whether it becomes a model — or a cautionary story — will depend on what we’re left with when the applause fades.