OpenAI introduced GPT-5.1, a reiteration with a consciously “playful” and “warm” aesthetic as the company ramps up its fight against having to hand over user chat logs in its copyright battle with The New York Times. The dual narratives — product buzz and courtroom clash — serve as reminders that personality and privacy are increasingly at the heart of A.I.’s next chapter.

What’s new in GPT-5.1, from behavior to reasoning upgrades

GPT-5.1 comes in two flavors: Instant, the crowd-pleasing workhorse that OpenAI said is its most used, and Thinking, a higher-reasoning version for more complex prompts. The model is more consistently obedient to instructions and applies what the company calls “adaptive reasoning” to know when it should take time to deliberate before answering — an attempt to keep the speed without losing depth on harder questions.

- What’s new in GPT-5.1, from behavior to reasoning upgrades

- Rollout and access for paid, enterprise, and free users

- Personality controls get granular with tone presets and styles

- Renewed clash with The New York Times over chat log discovery

- Privacy stakes and the law around discovery and user data

- What this means for users and developers adopting GPT-5.1

Early testers have described a default setting that is more conversational, which sounds approachable but breaks up better when pressed. In practice, that may be a code walkthrough that describes trade-offs instead of merely emitting snippets, or a research summary that highlights uncertainty and asks for answers before pinning down an interpretation.

Rollout and access for paid, enterprise, and free users

The update starts rolling out for paid tiers — Pro, Plus, Go, Business — before being made available to free and logged-out users. Enterprise and education customers receive a seven-day early-access toggle (its default setting is off) before GPT-5.1 will be the new base model service-wide. The gradual release is similar to OpenAI’s approach of putting up barriers between major changes and business plans as it tests the reliability and cost.

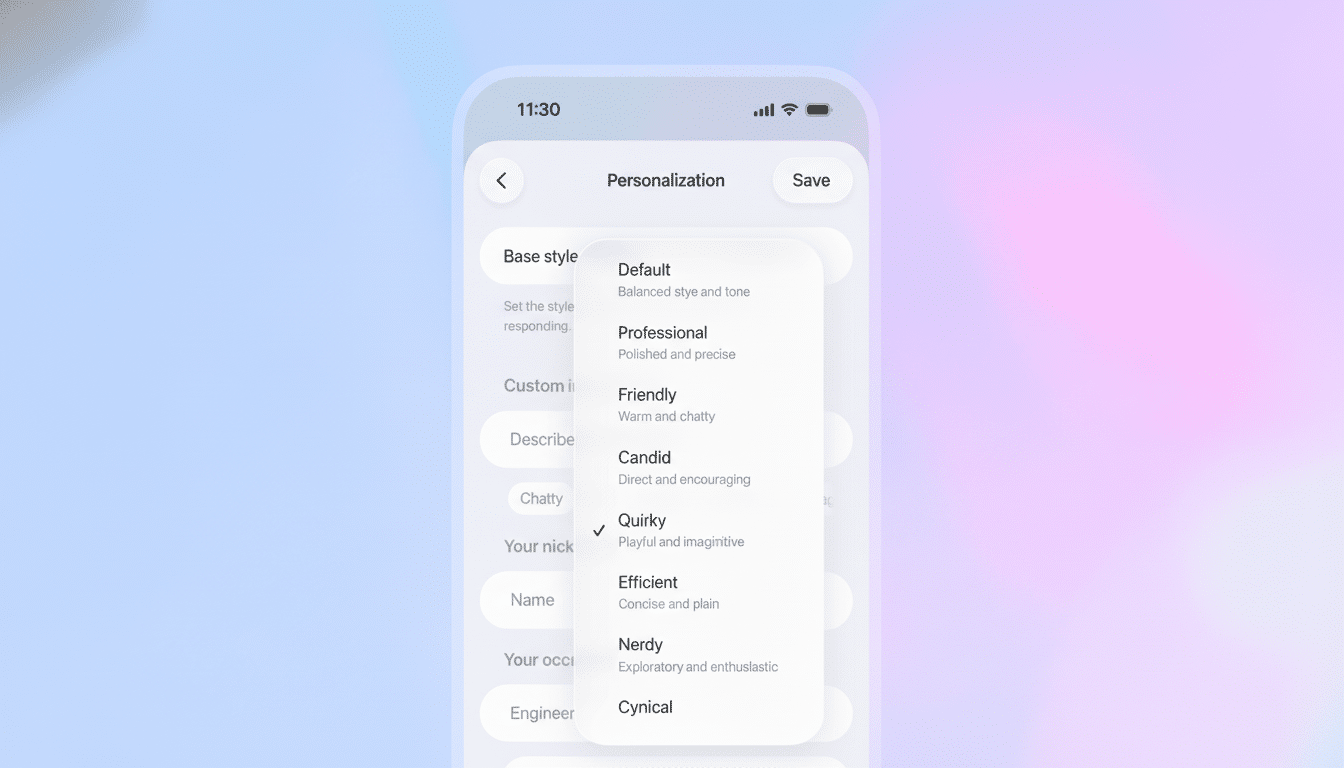

Personality controls get granular with tone presets and styles

In response to criticism that GPT-5 sounded cooler than GPT-4o, OpenAI is putting tone up front. Now users will be able to choose among six presets — Default, Friendly, Efficient, Professional, Candid and Quirky — or create a style of your own. CEO Sam Altman has claimed the model is better at instruction following and “adaptive thinking,” but admitted it overshot how much users like warmth in everyday prompts.

The strategy is pragmatic: Tone control matters for real work. A rep will have a different customer interaction in Professional than a brainstormer would with Quirky; the first draft of a legal memo has purpose to Efficient, while Candid can aid red-team critiques. This kind of knob is rapidly becoming table stakes as rivals embrace “agentic” behavior and a brand-safe persona.

Renewed clash with The New York Times over chat log discovery

GPT-5.1 lands as OpenAI refuses a court order to hand over 20 million ChatGPT conversations from discovery connected to the Times’ copyright lawsuit. The Times accuses OpenAI of training the system on its journalism without permission, and says the chatbot is able to regurgitate articles, sometimes word for word. OpenAI argues that the request oversteps and threatens user privacy, calling it a divergence from common-sense security practices.

In light of protective orders and de-identification processes, a magistrate judge is said to have taken issue with OpenAI’s privacy arguments.

OpenAI’s chief security officer Jason Kwon raised the idea of “AI privilege,” suggesting that the intimacy of prompts merits a new kind of protection, an argument that would be unprecedented in U.S. law and likely subjected to litigation.

Privacy stakes and the law around discovery and user data

Discovery is standard procedure in civil litigation, but chat logs are hardly routine material. Prompts are frequently filled with personal health details, workplace strategies, stabs in the dark — drafts of communications that were never sent or other narrowly avoided disasters. The scale — ChatGPT was used by more than 100 million weekly active users at its peak, according to OpenAI — has already been invoked in previous releases by the organization as evidence of how sensitive and risky it can be to mistreat even de-identified data. Digital rights defenders such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation have cautioned that de-identification can be fragile under rich, contextual datasets.

Relevance, burden and privacy are usually balanced by courts through protective orders, redactions and sampling. If that toolkit is enough for chatbot transcripts, then that will be a meaningful precedent for the entire industry, from enterprise copilots to consumer AI assistants. If the courts mandate broad disclosure, companies might stiffen data retention policies and default logging levels to reduce exposure to future litigation.

What this means for users and developers adopting GPT-5.1

For practitioners, GPT-5.1’s wager is apparent: more character with tighter logic. With tone presets, developers can maintain brand voice throughout support and marketing flows, while the Thinking variant aims for jobs such as data extraction, planning and multi-step coding. Teams whose governance model is based on the NIST AI Risk Management Framework or ISO/IEC 42001 would be expected to try out GPT-5.1 for hallucinations, latency and safety prior to widespread use.

Adoption has long had a legal shadow cast upon it. Companies that got into chat assistants early are already moving to tighter retention controls, privacy reviews and contract clauses restricting training on customer content. The result of OpenAI’s fight with the Times could hasten along that trend — or, if OpenAI wins on privacy protections, normalize responsibility for tightly controlled discovery around AI logs.

For the moment, OpenAI’s claim is simply that users will get a chattier companion without any compromise in rigor. The market will decide whether this warmer persona really makes the model more useful — or just more likable — and the courts how much of our conversations with machines belong in the public record.