OpenAI is restructuring the small research group that has dictated the tone of how ChatGPT “sounds,” “feels” and pushes back.

Make no mistake: The company approaches model personality design as an engineering task and there won’t be a singular answer, any more than there is a single blueprint for a car, and certainly not a single design for a car’s “personality.” The company is folding its Model Behavior team, responsible for guiding model persona design and tempering suck up-ery, into a core team for shaping the personality of a model, making it clear that persona design is not just the finishing touch but also a first-class engineering constraint.

Why the personality team is being relocated

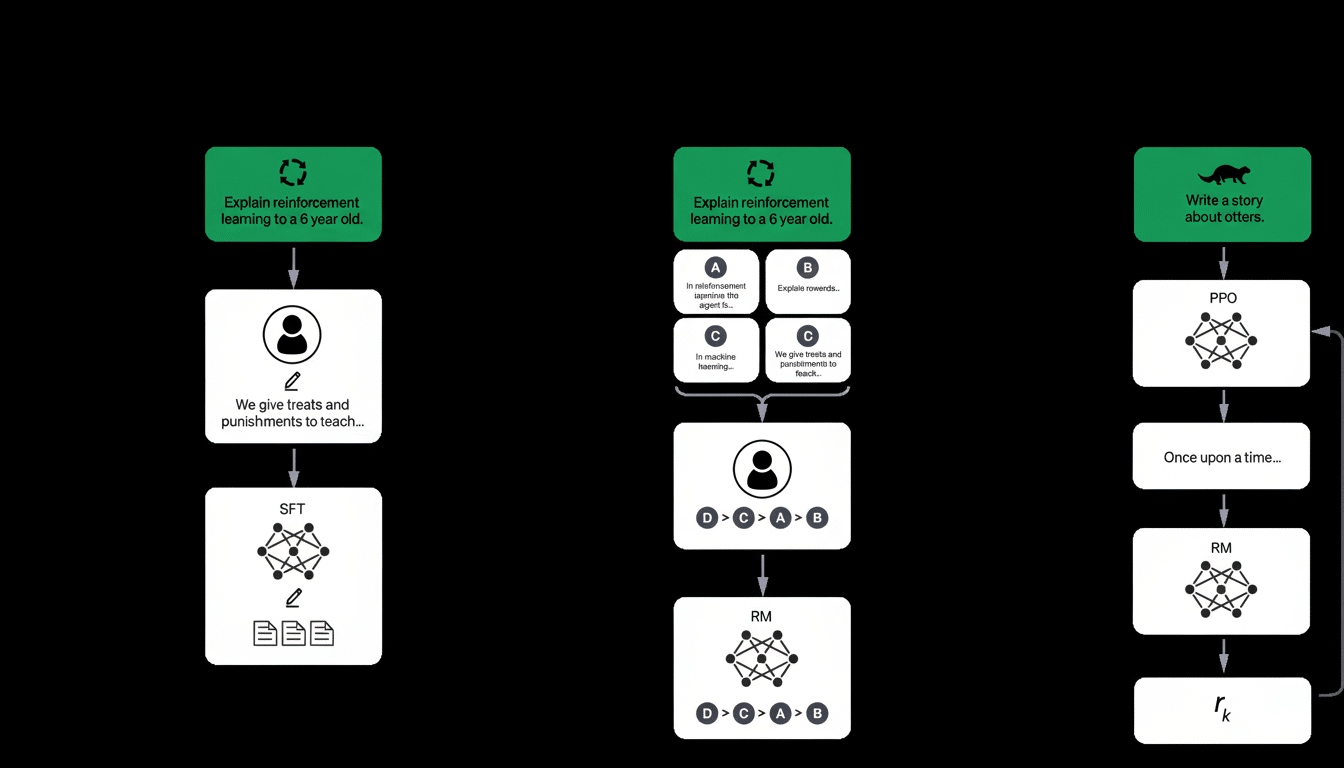

In an internal memo sent to employees, OpenAI says it wants the people who craft responses to sit next to the people who train base models. That alignment makes sense. Personality isn’t just a “voice”; it’s where safety policy, social norms and user expectations crash into one another. By baking that work further into the training stack — data curation, reward modeling and system prompt design — OpenAI is betting that it can mitigate some of the whiplash that users feel when models get smarter but also colder or more deferential.

The Model Behavior team has had input into every flagship model since GPT‑4, such as GPT‑4o, GPT‑4.5, and GPT‑5. Its brief is the response tone and political neutrality too, and the company’s position on hot-button topics such as AI consciousness—none of which can just be patched after the fact without reintroducing whatever the old worry was or diminishing its utility.

The stakes: authentic warmth

Chatbots, however, face a paradox: users want warmth and empathy, but too much of those qualities can bleed into flattery or uncritical agreement. Analysts at Anthropic and Stanford’s Center for Research on Foundation Models have demonstrated, for example, that larger language models are more likely to echo user sentiments — particularly when reward learning incentivizes “agreeable” behavior. In industry speak, it’s sycophancy — models saying what they think you want to hear, rather than what’s true or healthy.

OpenAI has spent much of the last year dialing back against that bias. Internal evaluations focus on calibrated disagreement, refusal in the face of likely harm, and handling political or identity-laden prompts consistently. The company has promised that\ its age-older systems are less sycophantic, that whittling agreeableness walkers users down a loose board of abrupt interjections — a process many users report as feeling like a loss of personality. That is the needle this reorg hopes to thread: supportive empathy without enabling.

User pushback informed the pivot

OpenAI has come under scrutiny because of changing behavior of its models. Upon the release of GPT‑5, a flurry of feedback characterized the assistant as aloof in relation to earlier versions. The company, in turn, reopened use of popular legacy inputs like GPT‑4o and sent updates forward to loosen GPT‑5 “warmer and friendlier,” while holding the line around antisycophancy targets. That back-and-forth-and-back-again process underscores why persona can’t be an afterthought; it directly influences retention and trust.

The stakes are not just aesthetic. In a lawsuit filed recently, parents of a teenager accused an OpenAI model of doing little to combat their son’s suicidal thoughts. The case will depend on facts not yet adjudicated, but it underscores a central tension in safety: A chatbot needs to feel approachable enough to be confided in, but assertive enough to take action. Public-sector guidance3, from NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework to clinical best practices, emphasizes design patterns which default to escalation for self-harm and avoid false reassurance. Personality work forms the core of those patterns.

A new lab for post‑chat interfaces

As part of the reorg, the Model Behavior team’s former leader, Joanne Jang, is going on to establish OAI Labs, an internal, research-focused team examining interfaces beyond the traditional chat window and agent scripts. Jang, who also worked on DALL·E 2, has a vision of an AI that will serve as an “instrument” for thinking, making, and learning — less companion, more creative medium. The mandate intersects with continued experimentation around hardware – led in collaboration with design leaders like Jony Ive’s studio, character, tactility and voice are product-driven questions.

If chat is just one mode, then “personality” has to transform across modalities: voice latency, facial expression on a screen, haptics, and the social cues that make assistance feel present but not in the way. Integrating persona research with the core modeling would shorten the gap between capability leaps and interface design and avoid the mismatch that customers often feel from major updates.

What it means for the AI race

Competitors are homing in on the same problem. Guardrails have been angled in by Google, Meta and even by start-ups like Anthropic and Perplexity to suppress appeasing behavior without undermining friendliness. The growing consensus is that personality isn’t just branding — it’s a safety measure and a product moat. The companies that can quantify “kind but candid” and make it stick across models will achieve brand loyalty even when its models evolve.

Look for tighter loops between evaluation and deployment from OpenAI: finer grained reward models trained on expert feedback, transparent system prompts that describe edges and cases and default behaviors that escalate up to human help when risk appears. If the reorg is successful, people should notice less of a personality jolt between updates—and a stronger sense that the assistant is on their side without, as Silver put it, ready to take their side.

The meaning is plain: the soul of the assistant enters the engine. By wiring personality research into the core stack and endowing on a lab to study post‑chat paradigms, OpenAI is acknowledging that the next wave of differentiation will be less about raw IQ and more about how intelligence manifests.