Nvidia came to CES with fewer eye-popping consumer announcements and a much broader agenda. The company drew the playbook of the next stage of AI, for robots, autonomous vehicles and cloud-scale infrastructure, during a media-packed Nvidia Live keynote.

The subtext was unmistakable. With a market value of over $5 trillion, according to Bloomberg data, Nvidia is positioning itself as less a maker of components and more as the operating layer for an AI-driven physical world.

Physical AI Gets Behind the Wheel of Autonomy

The headline idea was “Physical AI”: models that perceive, reason and act in the physical world after learning in simulation. Nvidia described this as the bridge from content generation to machines that can actually do something productive.

Two anchors stood out. Cosmos, a cosmological foundation model, is constructed to comprehend and forecast the development of objects and environments. Alpamayo focuses on driving following logic designed for challenging road situations and corner cases.

The highlight of the demo was a Mercedes-Benz CLA prototype driving with AI-defined parameters. Nvidia also said it wants to start a test Level 4 robotaxi service with a partner as soon as 2027, an indicator that the company is making the transition from autonomy supplier to operator of services.

That approach builds on Nvidia’s simulation stack — think Omniverse digital twins and Isaac robotics tools — to produce synthetic data, validate policies and compress years of road testing into safe, repeatable virtual runs before any wheels turn.

If successful, the payoff is huge: shorter development cycles for factories, warehouses and mobility fleets and better ability to adapt models quickly as regulations and local conditions change. It’s a practical way to scale, not just a showy demo reel.

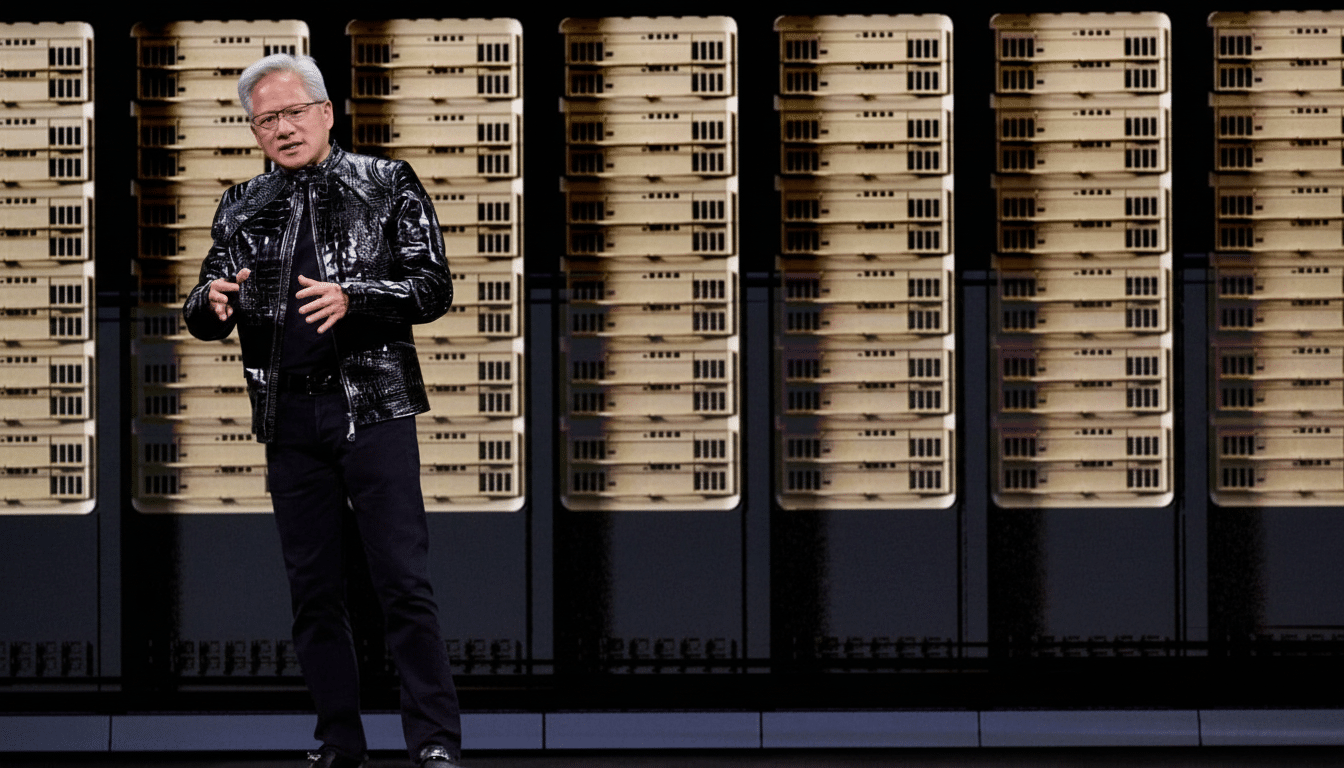

Rubin Calls for a Shift Toward Data Center First

There was no sign of any new GeForce cards, and that seemed intentional. Instead, Nvidia positioned Rubin, its next-generation AI platform that the company claimed is in production today, as a complete system that combines GPUs, CPUs, networking and storage into one tightly tuned fabric.

The message: The question of training and serving frontier models is no longer one of single-chip race, but data center integration. Real-world throughput is increasingly dictated by interconnects such as NVLink and high-performance Ethernet/InfiniBand, along with software scheduling.

This jibes with recent MLCommons research that has identified scaling efficiency and network bottlenecks as major limitations in training for large models. It also mirrors demand coming from hyperscalers and sovereign AI clouds that purchase systems by the pod, not by the part.

Energy was the unspoken variable. By 2026, the International Energy Agency estimates that global data center electricity consumption could reach 620–1,050 TWh (an amount largely driven by AI workloads). Rubin’s vow is to wring more useful compute out of each watt and rack unit.

If you’re a gamer, the humiliation of not having a nauseating GPU core count is more of a snub than it is an insult. Growth for Nvidia is now in training clusters and inference farms and enterprise pipelines where the total cost of ownership, not frame rates, controls buying.

Open Models as the New Lock-In for Developers

The third go at openness was hammered home at Nvidia through a series of promotional videos, all about sharing technology — if only on its terms. More than silicon, it showcased a raft of available-for-adaptation open AI models across healthcare, climate science, robotics, embodied intelligence and reasoning – each trained on Nvidia supercomputers.

Think: Earth-2 climate models for high-resolution prediction, robotic policies polished in Isaac simulators, and domain-specialized LLMs that can be fine-tuned with enterprise data. The pitch couldn’t be more straightforward: begin with strong baselines and then customize at speed.

There were even personal AI agents, powered on the DGX Spark hardware, in more of a one-on-one demo. It demonstrated an ecosystem that ranges from desk-side inference to hyperscale training — with Nvidia software, runtimes and acceleration libraries tying everything together.

There is a strategic catch. Nvidia’s stack remains where “open” models and toolchains still run best, most times first. And as analysts with Omdia and Dell’Oro say, Nvidia already has a stranglehold on AI accelerators; the more it can further normalize their use among developers, the better.

Collectively, Nvidia Live seemed less like a product teaser than like a manifesto. Physical AI goes from concept to road map, Rubin locks down a data center-first future and “open” models draw creators into the orbit. The through line is clear: Wherever AI lands — in a robot, in a car or on the cloud — Nvidia wants to be the ground upon which it stands.