NASA has ruled out a February attempt for the Artemis 2 launch after a key fueling rehearsal ended early, citing liquid hydrogen leaks, cold-weather impacts, and ground system glitches. The agency will pivot to an early-March window at the soonest, underscoring a familiar reality in human spaceflight: schedule yields to safety.

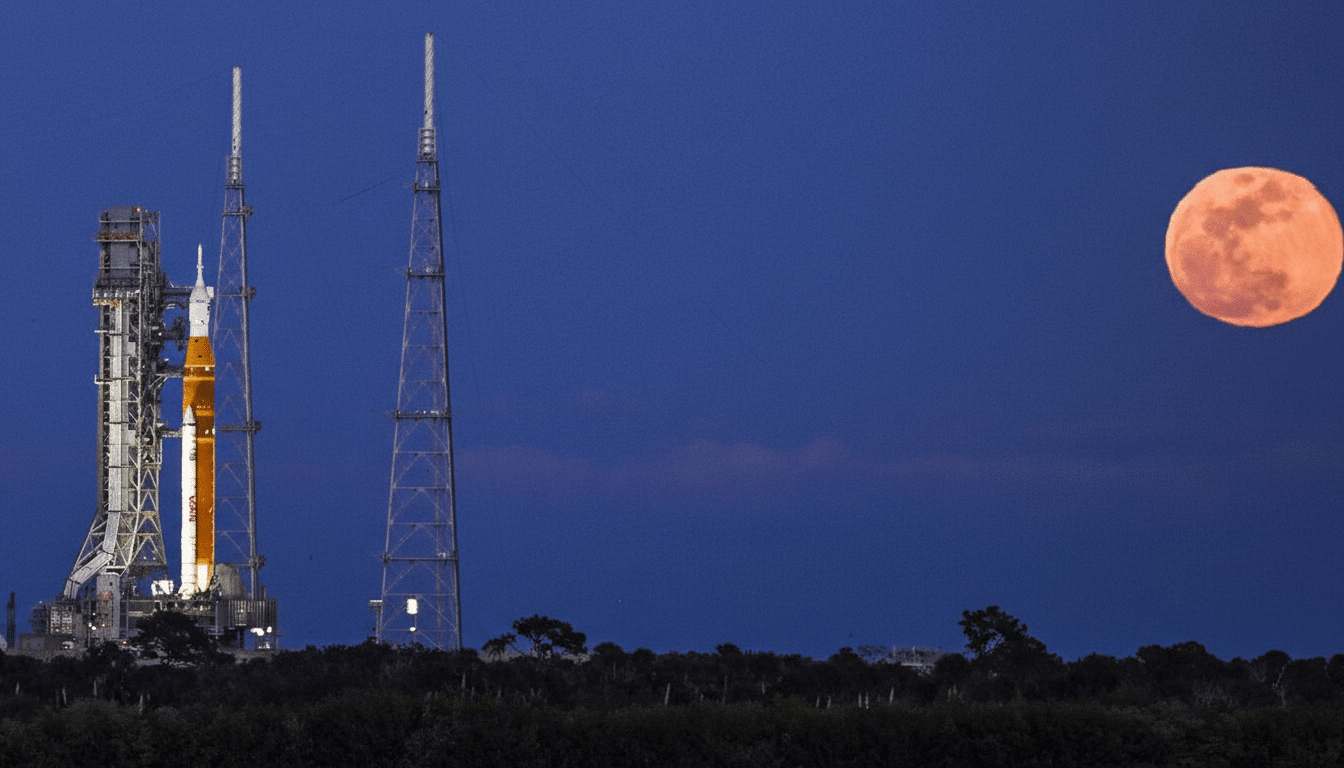

The wet dress rehearsal simulated a full countdown by loading roughly 700,000 gallons of super‑cold propellant into the 322‑foot Space Launch System and running pad “closeout” activities on Orion as if the crew were boarding. Controllers then safed and drained the rocket. The exercise is designed to flush out problems at the pad, not on launch day.

Managers will review the data, address hardware and software issues, and repeat at least one tanking test before setting a formal launch date. The decision keeps Artemis 2’s risk posture aligned with human‑rating standards.

Fueling Test Ends Early After Hydrogen Spike

Engineers spent hours troubleshooting a liquid hydrogen leak at a core stage interface during tanking, pausing the flow to warm the hardware, refit a seal, and adjust fill rates. Despite progress, the ground launch sequencer commanded an automatic cutoff with roughly five minutes left in the rehearsal when sensors registered a new spike in leak indications.

Cold conditions at the pad slowed operations from the start as teams conditioned lines and connections. A valve associated with pressurizing the Orion hatch needed retightening after a recent replacement. Multiple cameras and other pad assets suffered weather‑related disruptions, and ground networks experienced intermittent audio dropouts between control teams.

Even so, controllers fully loaded the rocket and dispatched a five‑person team to perform Orion closeouts as they would with astronauts present—an important validation of procedures. After the cutoff, propellants were safely drained and the vehicle transitioned back to a stable configuration.

Why Hydrogen Keeps Biting Rocket Launches

Liquid hydrogen is prized for high performance, but it is unforgiving. At about −423°F, it shrinks metals and seals, opening microscopic gaps. Its tiny molecules then exploit those gaps, particularly at quick‑disconnect umbilicals and valves. The result is a recurring technical thread across programs: leaks that appear only after hardware is cryo‑chilled.

Artemis 1 encountered similar leak‑driven scrubs that were tamed with revised procedures, seal swaps, and controlled warm‑ups. The Shuttle era saw the same pattern; several missions, including STS‑119 and STS‑127, endured multiple delays for hydrogen issues. The physics hasn’t changed—only the playbook for managing it.

Crew And Mission Profile Remain Unchanged

The four‑person Artemis 2 crew—Commander Reid Wiseman, pilot Victor Glover, and mission specialists Christina Koch and Jeremy Hansen—will fly a roughly 10‑day lunar free‑return. The flight is built to wring out Orion’s life‑support, deep‑space communications, navigation, and high‑energy reentry before NASA commits to a surface mission.

With February off the table, the astronauts will delay travel to Kennedy Space Center and resume quarantine closer to the next launch opportunity, typically about two weeks before liftoff, once NASA declares the vehicle ready.

Next Steps and Launch Windows After the Rehearsal

Teams will inspect liquid hydrogen quick‑disconnects, compare measured leak rates against flight rules, fine‑tune fill and drain profiles, and re‑verify ground communications. A repeat tanking test is planned to demonstrate stable cryogenic operations and clean comms before committing to a date.

The next target is an early‑March window with several viable opportunities. Window design is governed by translunar geometry, daylight splashdown constraints, range availability, and recovery conditions in the Pacific. Range safety, weather, and leak‑rate margins must all line up to earn a “go.”

Practically, the gating metrics include leak thresholds measured in grams per second, stable temperatures across critical interfaces, and uninterrupted voice/data links. Meeting those benchmarks turns a rehearsal into a launch posture.

The Bigger Picture for Artemis and Program Outlook

Artemis 2 is the human‑rated bridge between the uncrewed Artemis 1 and the first surface attempt of Artemis 3. It validates the integrated SLS‑Orion stack with people aboard. The SLS Block 1 configuration can send roughly 27 metric tons on a translunar trajectory, but the capability matters only if the system is operated conservatively and predictably.

Independent watchdogs, including the Government Accountability Office and the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, have consistently warned against schedule pressure. NASA’s move to pass on February reflects that guidance. The goal is unchanged: one clean countdown, a safe lap around the Moon, and a steadier path to the next giant leap.