NASA says crewed lunar travel is shifting from dream to schedule, with a 2026 trip set to send astronauts back to the Moon for the first time in more than five decades. The flight, which will be part of the Artemis program, is meant to validate that the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft work on a real crewed trip around the Moon before subsequent jaunts attempt to land astronauts on its surface.

The crew and the plan for NASA’s 2026 lunar flyby mission

The quartet of crew members reads like a who’s who of recent spaceflight. Thanks to these incredible individuals for being there with us today! pic.twitter.com/Z3SsXtrnj4

The mission will be commanded by NASA’s Reid Wiseman, who will pilot the spacecraft alongside Victor Glover and Christina Koch as second pilot and mission specialist. That’s in addition to Jeremy Hansen, of the Canadian Space Agency — a seat earned by Canada’s pledge to supply next-generation robotics for future lunar infrastructure.

The mission, in high Earth orbit, is expected to shake down Orion’s life-support equipment and communications before the spacecraft embarks on a set of trans-lunar injection burns. From that point, the crew would execute a free-return flyby: slingshotting around the far side of the Moon and allowing gravity to fling them home. Orion will employ a so-called skip reentry profile at some 25,000 mph, allowing it to dip into the atmosphere twice to handle extreme heating before returning for a parachute descent and splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

In addition to proving out the hardware, the astronauts will test manual handling qualities, go through checkouts using NASA’s Deep Space Network, and record cockpit workload and radiation exposure — inputs that are used to help develop procedures for lengthier lunar expeditions.

Hardware and readiness for NASA’s Artemis lunar mission

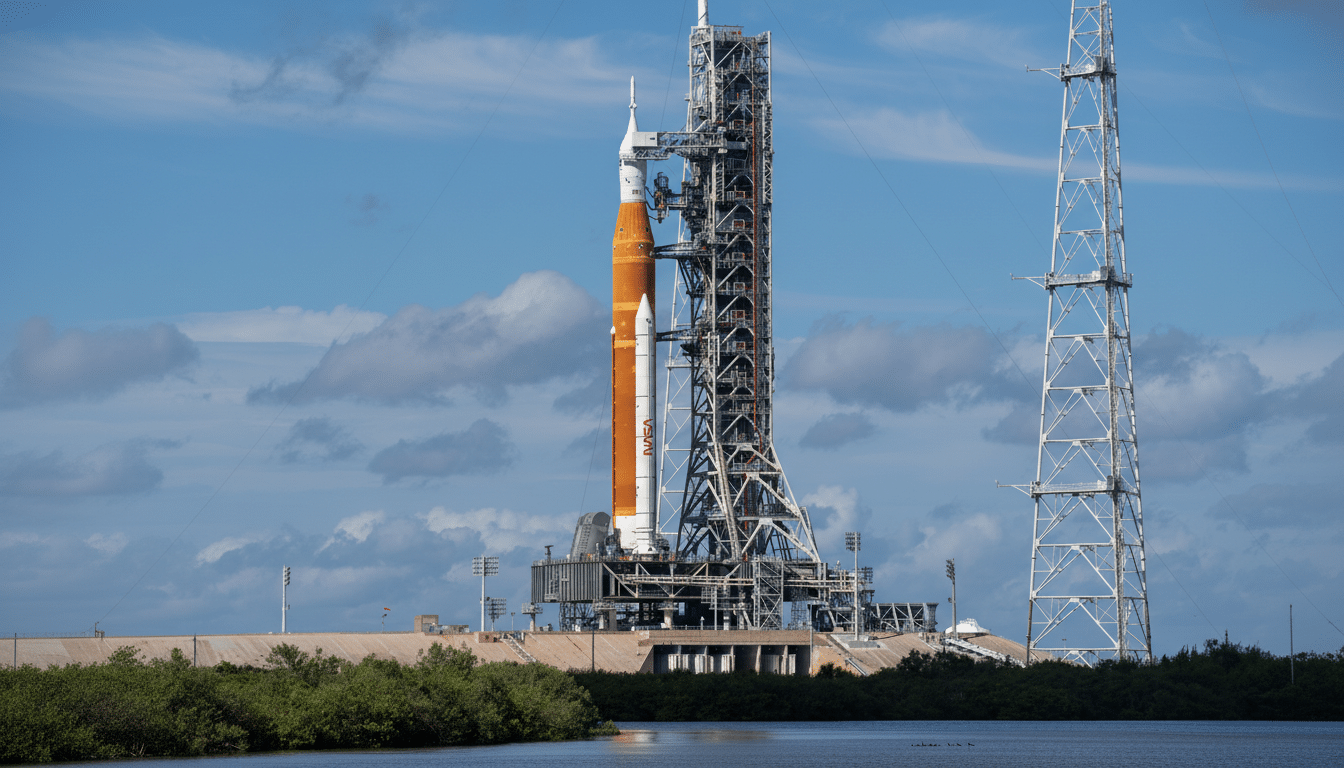

Artemis is the crewed mission slated to launch aboard the Space Launch System, NASA’s most powerful rocket ever flown, which produces some 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff. With a long shuttle legacy, the core stage is propelled off the pad by four RS-25 engines, flanked by two five-segment solid boosters to muscle the stack aloft.

Orion, designed for deep space, features a U.S.-built crew module and spacecraft adapter, and Europe’s service module provided by the European Space Agency. You don’t buy these components from ISS’s international partners, NASA’s station program manager Mike Lammers tells us: “ESA provides the power, thermal and propulsion module — including a main engine that came from shuttle OMS [orbital maneuvering system] — so we co-crafted an architecture that needs its modules.”

Operationally, NASA is planning for a wet dress rehearsal to occur on the launch pad that will load cryogenic propellants to simulate countdown procedures. Rolling atop the Crawler-Transporter, a 4.2-mile journey that qualifies as one of Florida’s best-managed commutes, is the integrated stack bound for Kennedy Space Center’s Pad 39B. A subsequent flight readiness review will authorize liftoff.

Lessons from the uncrewed Artemis I mission are built into the checklist. Engineers looked at the char behavior of Orion’s heat shield, fine-tuned material margins, and reverified parachute performance with drop tests, while they also completed life-support work that could not have been exercised without astronauts on board. Watchdog groups like the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel have cited those changes as critical risk-reduction makeovers.

Why a 2026 mission matters for sustained lunar exploration

This flight is the turning point from demonstration to sustained exploration. If success is achieved, it takes us a step closer to a lunar surface campaign at the south pole — the lunar polar areas, brimming with permanently shadowed craters, where orbital information collected by missions such as the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and LCROSS shows water ice is likely present. Downrange dependencies are critical. This surface landing is reliant on the availability of a Human Landing System prepared by a private firm, which will use SpaceX’s Starship with on-orbit refueling and propellant transfer. It also necessitates designing new lunar spacesuits, which may be supplied by industry partners such as Axiom Space.

The geographical context is critical. China has announced the objective of launching a human lunar landing near 2030, inspired by China’s accomplishments with its robotic Chang’e program. India’s space program has recently marked its first south polar landing, Chandrayaan-3. Meanwhile, U.S. commercial deliveries via CLPS are engaged in instrument and technology demos on the lunar surface; Intuitive Machines’ spacecraft, Odysseus, demonstrated operations and navigation tech on the Moon. The south pole is not merely a destination but a significant aspect of progress. Water ice can be used and, if accessible, converted into hydrogen-oxygen rocket propellant, which can help reduce the challenges of sustained lunar operations and eventual Mars visits. The Artemis design calls for a succession of regular trips, a small Gateway station in lunar orbit, and surface structures that can survive the two-week-long night.

In the science column, there are geophysical networks to be deployed by astronauts and pristine samples to return from ancient crater rims, with on-the-ground readings informed by orbital observations. The radiation and space weather data collected on this mission will inform shielding standards for those longer visits.

What to watch next as NASA readies the Artemis lunar flight

Key events include the rollout to Pad 39B, the wet dress rehearsal readiness test, and the final flight readiness review that aligns launch windows, weather conditions, and range activity. Look for joint U.S. Navy crew recovery training; end-to-end communications tests with the Deep Space Network; and more integrated practices that synchronize crew timelines with ground control.

In 2026 or so, if all goes as planned, NASA will have reopened a transportation gateway to deep space that was closed with the last Apollo Moon mission in 1972. That one act — astronauts orbiting the Moon once more — will transform a decade of construction into forward motion, and nothing else in exploration is rarer than forward motion.