NASA is pressing ahead toward the first crewed Artemis flight even as it labels Boeing’s recent Starliner test with astronauts a Type A mishap, the agency’s most serious incident classification short of loss of crew. The dual track of launching to the moon while reckoning with a high-severity failure underscores how tightly NASA is tying culture and accountability to hardware readiness.

Starliner Reclassified At The Highest Severity

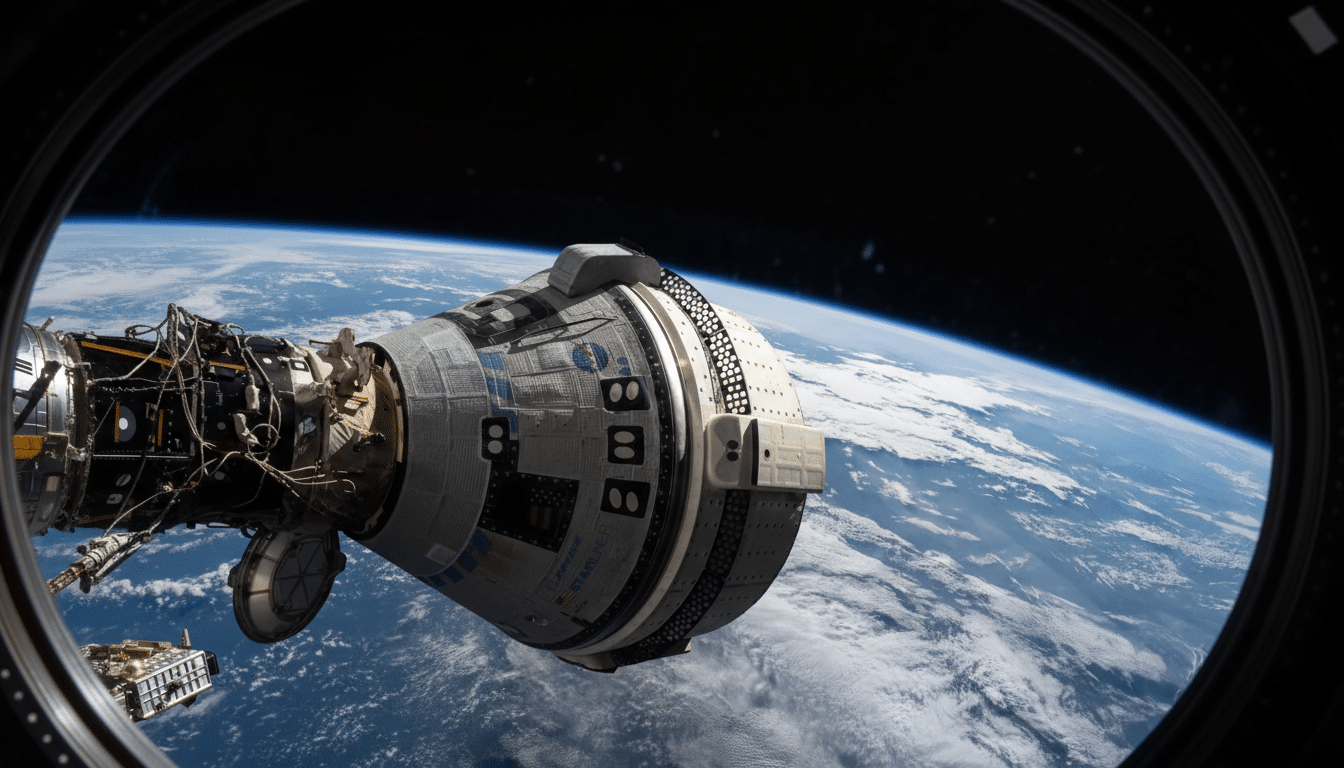

Under NASA’s mishap policy, a Type A event triggers the toughest level of scrutiny, independent reviews, and formal reporting to Congress. The reclassification follows an investigation into Starliner’s crewed test flight, which suffered propulsion system anomalies, helium leaks, and thruster performance problems that forced a change of plans and kept the two astronauts in orbit for months longer than intended.

NASA leaders acknowledged not just technical issues but breakdowns in oversight and decision-making, emphasizing that risk was not adequately retired before key milestones. Boeing has said it is implementing design fixes and cultural reforms, aligning with the agency’s findings that call for systemic improvements across Commercial Crew partners to protect mission and crew safety.

The mishap board cited episodes of degraded attitude control and propulsion faults, including during rendezvous and the later uncrewed return of the capsule’s service module. That return-phase anomaly was not fully disclosed in real time, a gap the agency now says it intends to close with more transparent reporting standards going forward.

Why the Label Matters for Artemis 2 Mission Readiness

Artemis 2 will fly a four-person crew on Orion for a lunar flyby, using a different spacecraft and rocket than Starliner. Even so, NASA officials stress the Starliner lessons are immediately relevant: configuration control, fault management, margin tracking, and frank communication under schedule pressure are cross-program imperatives.

One example is Orion’s heat shield, which showed more abrasive than predicted char loss during Artemis 1. NASA’s engineering teams say the margins remain acceptable, but they are updating models and inspection criteria before certifying the vehicle for humans. The agency has also expanded hazard analyses and fault-tree depth to capture off-nominal interaction effects—precisely the kind of systems thinking highlighted by the Starliner investigation.

External overseers have been delivering the same message. The Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel has repeatedly warned against allowing schedule to dominate risk decisions in Artemis, while the Government Accountability Office keeps NASA’s major acquisitions on its High-Risk List because of cost and schedule volatility. The NASA Inspector General has estimated early SLS/Orion missions cost roughly $4.1B per launch, raising the stakes for mission assurance and configuration discipline.

Latest Tests Show Progress But Work Remains

In the latest wet dress rehearsal, teams loaded the Space Launch System’s core and upper stages with cryogenic propellants, executed planned holds, and practiced terminal count procedures. Leak rates—especially liquid hydrogen—stayed within limits after ground crews swapped seals and a filter between rehearsals, a notable improvement over earlier campaigns that were frustrated by small yet consequential leaks.

Key open items include re-verifying the flight termination system, a safety-critical range requirement that demands precise retesting on the pad, and completing Orion closeouts tied to avionics checks and environmental control loops. A formal flight readiness review will integrate these products with program-level risk acceptance before an actual launch attempt is set.

Mission operators also rehearsed contingency procedures designed to reduce cognitive load on the crew and controllers, from scrub turnarounds to recycle logic. Those refinements answer a common ASAP critique: that complex launch systems must be operable under stress, not just nominally safe on paper.

A Pledge Of Transparency And Cultural Reset

NASA leadership says the Starliner Type A designation is more than a label; it is a public commitment to trace causes to closure. That includes releasing substantive findings, documenting corrective actions, and sharing enough test data to build trust without compromising proprietary details or export-controlled information.

Internally, programs are being asked to strengthen dissent channels, sharpen independent technical authority, and ensure risk is carried explicitly to boards rather than diluted by optimistic language. Those moves echo best practices identified in past probes—from Columbia to more recent safety reviews—that emphasize that culture can either catch small problems early or compound them into crises.

With Artemis 2 approaching and the Starliner report in hand, NASA is trying to demonstrate it can do both at once: resolve serious mishaps with candor and launch a high-profile mission only when engineering evidence, not calendar targets, says it is ready. The measure of success will be visible in checklists, not slogans—quiet margins, clean data, and a crew that returns home with a mission’s worth of lessons rather than a mishap’s.