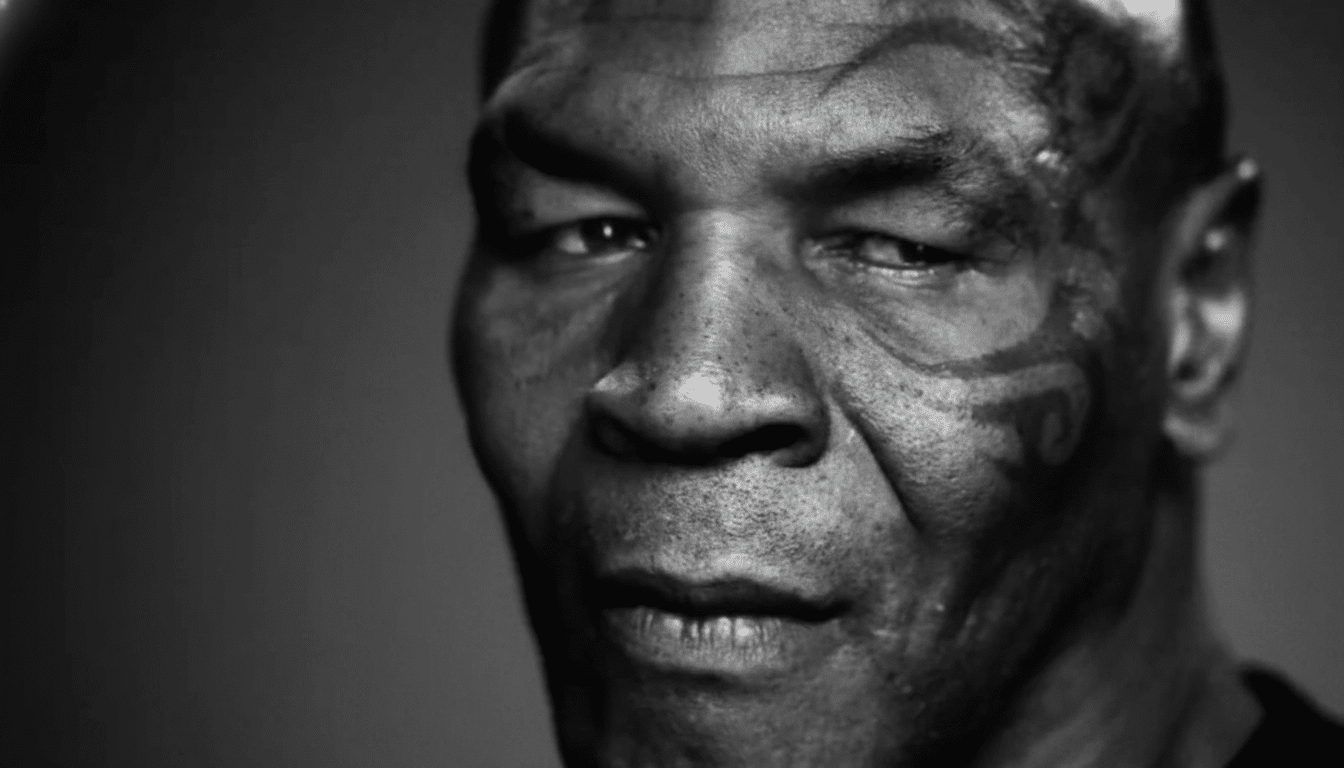

The Mike Tyson Super Bowl spot billed as a hard reset on America’s eating habits instead delivered a masterclass in what not to do in public health. Anchored by a stark confession about weight and despair, the ad leaned on fear, shame, and a simplistic “real food” mantra—without offering meaningful solutions or acknowledging the structural realities that shape what people can eat. For a campaign seeking credibility on health, it landed like a punch that misses the target and injures the audience.

Why Fear and Shame Miss the Mark in Health Messaging

Decades of research show that fear appeals backfire when they are not paired with clear, feasible steps people can take. Communication scientists often cite the Extended Parallel Process Model: if a message spikes fear but withholds efficacy—what to do, how to do it, and why it will work—people disengage or deny the risk. That’s why organizations like the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urge campaigns to match risk information with specific, accessible actions and supportive tone.

This ad offered neither. Viewers heard moralized language about bodies and “real food,” but no directions on affording produce, finding healthier options in low-access neighborhoods, or securing support from healthcare providers. Without efficacy, fear morphs into stigma—and stigma is not a treatment plan.

Stigma Is Not a Treatment for Better Health Outcomes

U.S. adult obesity prevalence sits around 42% according to the CDC, a statistic that reflects complex drivers: economics, marketing, built environments, stress, medications, genetics, and more. The ad’s framing collapses that complexity into personal failure. Evidence says that approach harms health. Research from the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health has linked weight stigma to higher stress hormones, disordered eating, avoidance of medical care, and lower physical activity. One longitudinal study found that experiencing weight discrimination was associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality over time.

Clinical guidance echoes the risks. The American Academy of Pediatrics advises person-first language, screening for disordered eating, and comprehensive, family-based approaches. The American Psychological Association cautions that shaming bodies fuels anxiety and depression rather than lasting behavior change. When public messages equate body size with moral worth, people tune out—or get hurt.

Suicide Messaging Rules Were Ignored in the Ad

The ad’s references to suicidal thoughts violated widely accepted media standards. The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention and WHO advise avoiding sensationalized depictions, steering clear of uncontextualized first-person accounts in mass advertising, and always pairing difficult content with hope, resources, and clear avenues for help. Those safeguards exist because careless messaging can increase risk for vulnerable viewers. In this case, raw disclosure was used as a scare tactic about body size—without helplines, clinical resources, or evidence-based supports. That is not edgy; it is irresponsible.

The Structural Reality The Ad Refused To Name

Americans do not make choices in a vacuum. The USDA estimates tens of millions live in food-insecure households, and studies suggest more than half of the average U.S. diet comes from ultra-processed products heavily engineered and marketed by multinational firms. Neighborhood design, transit access, school meal quality, retail pricing, and industry lobbying all shape what ends up on the plate. Any serious effort would address those levers: expand and modernize SNAP and WIC, fund universal school meals with healthy standards, improve food retail in underserved areas, and align healthcare incentives with “food is medicine” programs.

The ad also skipped basic public-health hygiene: no call to action, no cost supports, no pointers to community programs or registered dietitians, no acknowledgment of primary care or mental health access. A prime-time platform was used to scold viewers rather than equip them.

What Effective Health Campaigns Actually Do

Campaigns that change behavior blend emotion with practicality and trust. The CDC’s “Tips From Former Smokers” worked because searing personal stories came with specific quit resources and covered treatments. In nutrition, successful interventions pair messaging with concrete supports: produce prescription programs that lower out-of-pocket costs, community health workers who coach goal-setting, workplace and school environments that make the healthy choice the default, and clinician training that avoids bias while addressing sleep, stress, medications, and social needs.

Messaging also matters. Person-first language, neutral descriptions of foods, and goals framed around function—more energy, better sleep, improved labs—outperform body shaming. When medications such as GLP-1s are indicated, evidence-based care integrates them with nutrition counseling, physical activity, and mental health support, rather than mocking or glamorizing quick fixes.

A Squandered Moment for Evidence-Based Public Health

The Super Bowl is one of the few moments when a health message can reach nearly everyone at once. This ad squandered that reach, choosing humiliation over help and spectacle over substance. Public health succeeds when it builds trust, reduces barriers, and offers people tools that fit the realities of their lives. Shame changes channels, not behavior. The next campaign should invest in evidence and dignity—and finally give Americans something actionable to do with their concern.