Microsoft provided the FBI with BitLocker recovery keys to unlock encrypted laptops tied to a federal probe, according to multiple reports, spotlighting how Windows’ default key backups can translate into lawful access for investigators—and a fresh wave of privacy and security questions for users.

What the reports say about FBI BitLocker keys

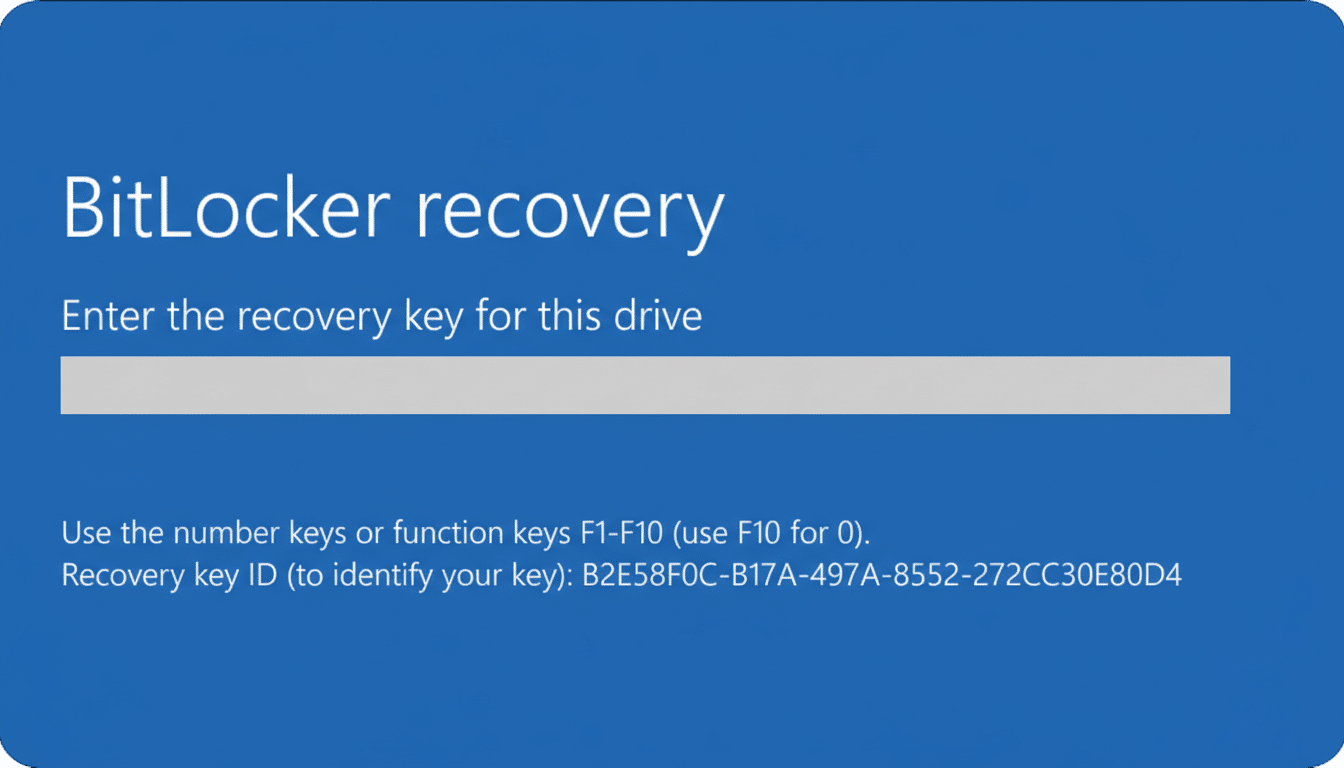

Forbes reported that Microsoft supplied recovery keys for three BitLocker-protected laptops seized in an investigation involving alleged Pandemic Unemployment Assistance fraud in Guam. Local outlets Pacific Daily News and Kandit News previously noted court filings indicating that a warrant sought keys associated with the suspects’ devices after law enforcement had already taken possession of the hardware.

Microsoft did not comment in the reporting cited, but the company—like most major tech firms—has long said it responds to valid legal process. The scenario is notable less for the warrant itself than for the technical path it leveraged: BitLocker recovery keys that many Windows machines automatically store with Microsoft.

How BitLocker recovery keys end up in the cloud

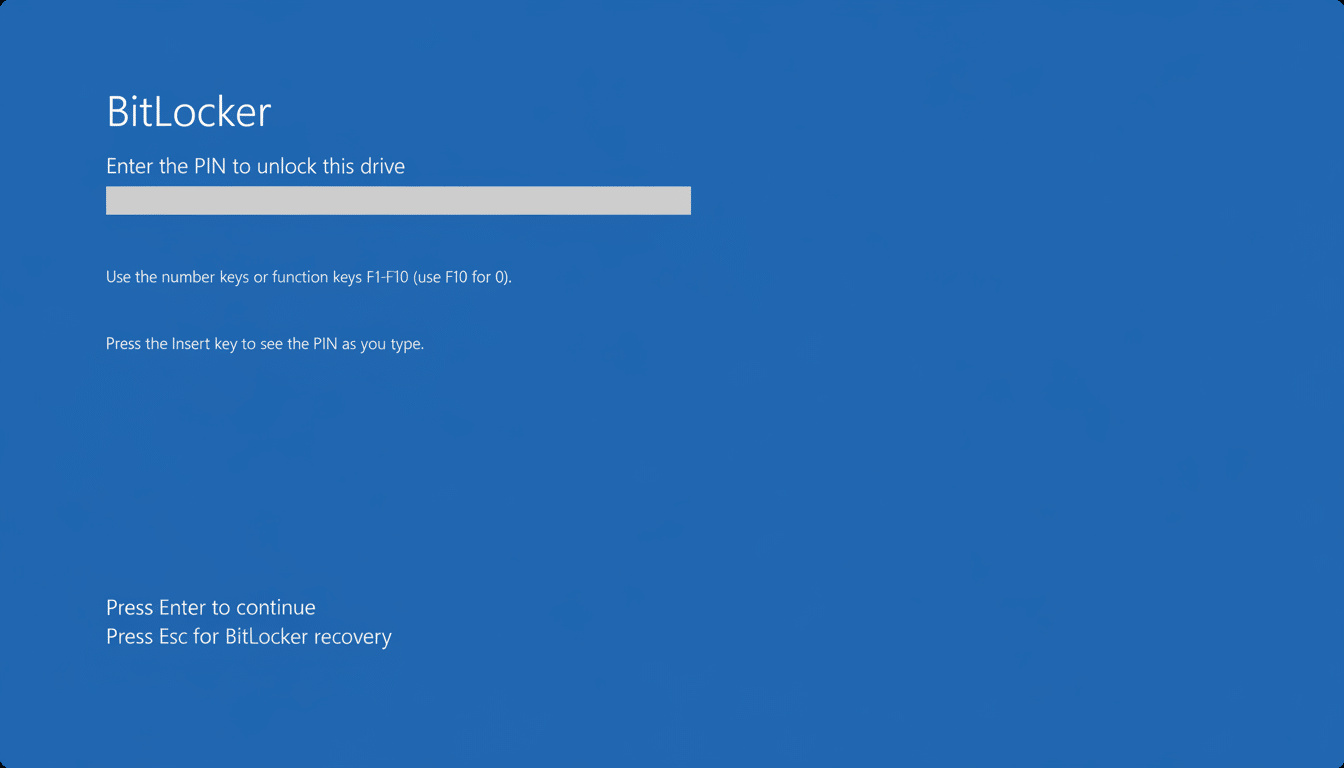

BitLocker, Microsoft’s full-disk encryption, often sits on by default when users sign in with a Microsoft account on modern Windows laptops. In those setups, a 48-digit recovery key is typically backed up to the user’s account in Microsoft’s cloud. On corporate devices, keys are commonly escrowed to an organization’s directory service, such as Entra ID (formerly Azure AD), where administrators can retrieve them.

Those backups are intentional: they prevent permanent lockouts if a device fails or a user forgets a PIN. But they also create an avenue for lawful access. If a court orders Microsoft or an employer to produce a recovery key, the encrypted drive can be unlocked—no brute forcing required—once investigators have the physical device.

Security and privacy implications of key escrow

Cryptography experts have warned for years that centralizing recovery keys increases systemic risk. Johns Hopkins professor Matthew Green noted that any compromise of key escrow systems could have wide blast radius, especially if an attacker also obtains devices or drive images. His caution echoes findings from the federal Cyber Safety Review Board, which criticized aspects of Microsoft’s security culture after high-profile incidents, including the theft of a consumer signing key in a 2023 cloud intrusion and a separate nation-state breach of corporate email accounts.

The flip side is the public safety case for access. During the pandemic, unemployment insurance fraud losses in the United States were estimated in the tens of billions of dollars. Investigators argue that timely decryption can expose financial trails, conspirators, and victims. The Guam case underscores how recovery-key pathways can materially speed investigations compared to device exploitation or expensive third-party workarounds.

Consumer versus enterprise realities for BitLocker

For consumers on Windows Home or devices with “Device Encryption,” key backup to a Microsoft account is typically enabled with little or no friction at setup. For Windows Pro and Enterprise, organizations can enforce policies that escrow keys internally, require pre-boot PINs, or disable cloud backup entirely. In both models, the recovery key—if it exists—will unlock the drive regardless of whether a PIN or TPM-based protection is configured.

Practically, that means corporate IT and cloud providers become critical trust anchors. If they store the keys, they can be compelled to produce them. If they do not, law enforcement must look elsewhere, as seen in past standoffs over encrypted smartphones where companies claimed they had no keys to give.

What users and admins can do to manage recovery keys

Users concerned about cloud-stored recovery keys can review their Microsoft account to see whether keys are present and remove backups where policy allows, keeping an offline copy in a secure location. On Windows Pro, Group Policy and command-line tools let owners disable cloud backup and add pre-boot PINs. Enterprises should audit key-escrow practices, restrict who can retrieve keys, enforce strong administrative controls, and apply separation of duties with logging and alerts.

Security posture matters beyond encryption: device tamper protections, firmware updates, and phishing defenses all reduce the odds that an attacker ever gets close to a protected drive. But for threat models that include compelled disclosure or targeted cloud compromise, minimizing third-party custody of recovery secrets is a rational step.

The larger policy debate around lawful access

This episode highlights a subtle but important distinction in the encryption debate. Unlike proposals to weaken cryptography or mandate backdoors, BitLocker’s recovery-key escrow is a usability feature that doubles as an access mechanism under court order. It delivers a form of lawful access without breaking the math, but it concentrates risk and shifts the privacy burden onto configuration choices and institutional safeguards.

As more data protection defaults move into the cloud, expect greater scrutiny of who holds recovery credentials, under what policies they’re stored, and how often they are accessed. For now, the takeaway is straightforward: if a recovery key exists in a place a third party controls, it is accessible—to you when things go wrong, and to authorities when a judge says so.