Last Energy, a nuclear startup pursuing a steel-encased microreactor design, has raised $100 million to further its power-trajectory tech and refocus fresh attention on small modular reactors as energy-hungry industries jostle for stable electric supplies that are also carbon-free. “This Series C funding, led by Astera Institute with participation of AE Ventures, Galaxy Fund, Gigafund, JAM Fund, The Haskell Company, Ultranative, Woori Technology and others, will allow us to finalize our first pilot and to progress toward initial commercial deployments,” Ace Glassman, the company’s founder, said.

What Last Energy Is Creating With Its 20 MW Microreactor

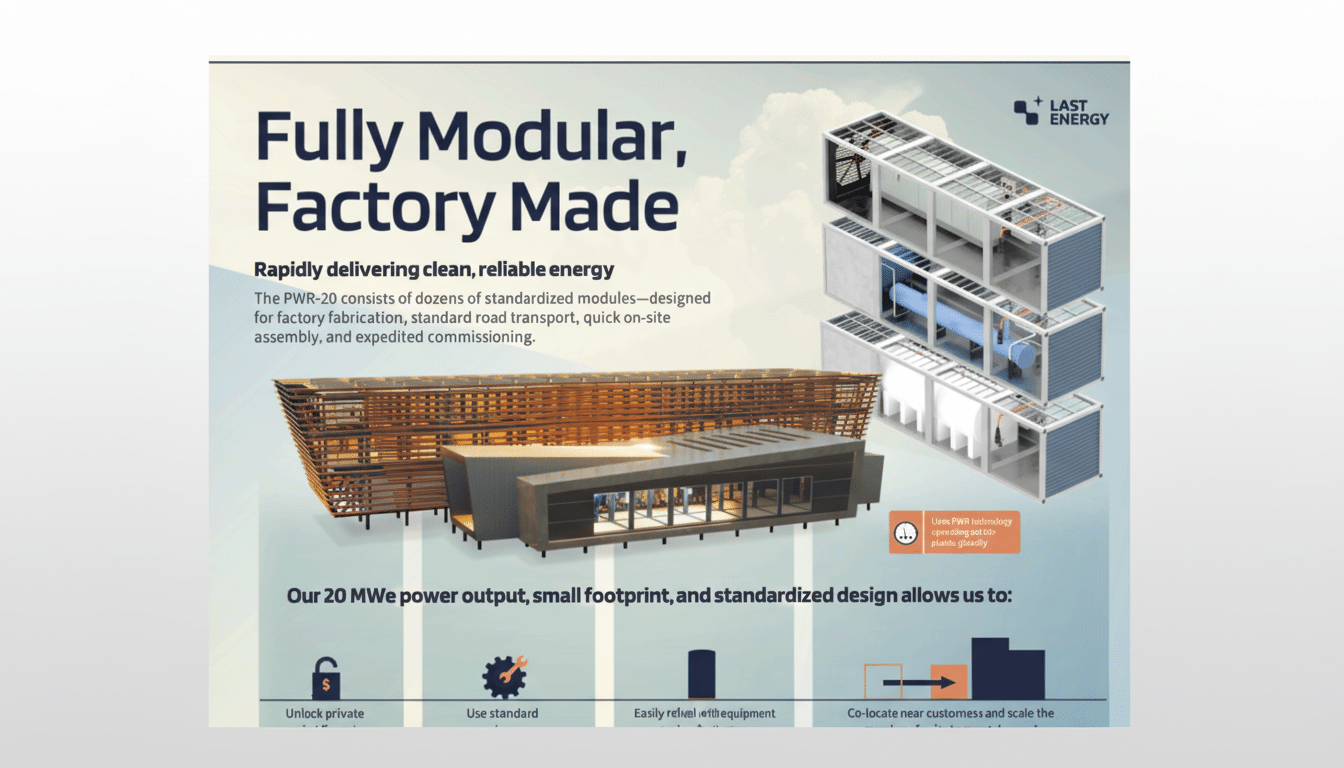

Last Energy’s design is a small, pressurized water reactor (PWR) that is capable of generating 20 megawatts of electricity, a capacity suitable for data centers, industrial parks and large campuses. The company plans to get started with a 5 MW pilot prior to scaling up the full commercial unit, said Schmidt, adding that it will keep the hardware simple and repeatable in order to support factory-style manufacturing as well as faster siting.

- What Last Energy Is Creating With Its 20 MW Microreactor

- Why This Steel Monolith And A Permanently Sealed Core

- Market tailwinds and the evolving competitive landscape

- Unit economics in focus for microreactor deployment

- Regulatory and safety considerations for sealed designs

- What the funding enables for pilot and scale-up plans

- Outlook for Last Energy’s sealed-steel microreactor path

Instead of creating an original fuel and sustainability paradigm, however, the team is revitalizing a proven government-era PWR design heritage that has its roots in the NS Savannah, the world’s first nuclear-powered merchant ship. This is a strategic gambit that builds on decades of experience operating PWRs to shorten the qualification cycle — with reliance on existing fuel and component supply chains, staying ahead of infrastructure gaps that dog other designs requiring next-generation fuels.

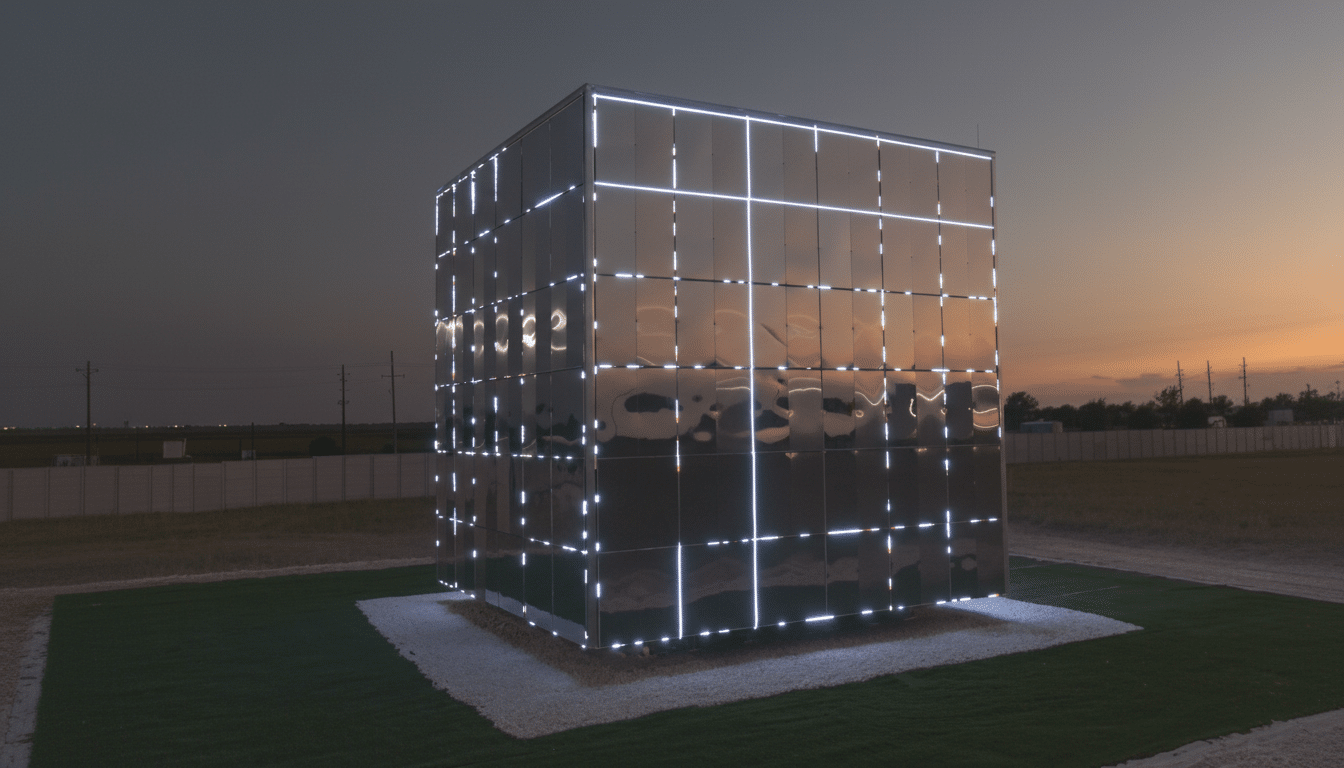

Why This Steel Monolith And A Permanently Sealed Core

Key to this strategy: a steel monolith the size of thousands of subway cars, permanently sealed as the reactor’s containment and then as its waste cask at end of life. Each core is encased in around 1,000 tons of steel. Last Energy estimates the steel alone at around $1 million per unit — a number that is less than that required for specialized, nuclear-grade concrete and complex penetrations typically found in conventional plants.

The steel vessel is heated by the core in operation. Water that’s piped through the outside tubes absorbs that heat and drives a steam turbine, so there are no penetrations through the steel wall other than electrical and control links. The reactor is fueled for six years from the beginning, and its design does not allow it to be serviced midway through life; when shut down, its steel body doubles as a storage cask without further spent-fuel handling.

And the tradeoff is as much philosophical as technical: design out maintenance to design out complexity. Fewer moving parts inside the boundary reduce failure modes and regulatory headaches, but they require ultra-reliable components, thorough factory testing and a robust strategy for monitoring all of the equipment to placate safety regulators.

Market tailwinds and the evolving competitive landscape

SMRs are riding a wave of interest as grid queues lengthen and firm, around-the-clock power grows scarce. The International Energy Agency has cautioned that global data center electricity use is skyrocketing and may nearly double in a matter of years as AI and cloud continue to grow. That’s pushing hyperscalers and industrials to pursue “behind-the-meter” generation that bypasses transmission bottlenecks.

Investors are responding. In recent months, several nuclear ventures have closed large rounds, including high-temperature gas reactor and microreactor plays. The field is varied — some teams are aiming for advanced fuels and industrial-heat-level temperatures; others, including Last Energy, favor providing lights that haven’t gone out since the 1950s with proven light-water technology made quickly. The unifying theme is a willingness to reimagine delivery models, from modular manufacturing to single-site, load-focused power purchase agreements.

Unit economics in focus for microreactor deployment

One unit could thus produce on the order of 150 to 160 GWh per year, at typical nuclear capacity factors and with an output of 20 MW. For constrained customers, this is the difference between growing compute or waiting years in an interconnection queue. On the supply side, the company is reliant on manufacturing scale — what industrial economists call learning curves — to squeeze costs as volume expands. Wright’s Law, apparent with aerospace and semiconductor production too, predicts steep cost reductions for every order-of-magnitude increase in cumulative production — but regulatory overhead can dull the curve on nuclear.

A steel-first approach may help. Standard plate steel construction taps shipbuilding and petrochemical skills found in a number of areas, relieving bottlenecks seen with large nuclear projects using ultra-large forgings and custom-built civils.

Regulatory and safety considerations for sealed designs

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission is in the process of creating abbreviated paths for microreactors and advanced designs, but licensing still can be a rigorous, years-long exercise. Last Energy’s sealed-vessel approach will probably be compared with other containment integrity, passive safety and post-shutdown storage schemes. Since the steel monolith is to be sited in situ beyond decommissioning, the design will also have to show it can satisfy long-term storage criteria covering shielding, heat extraction and protection.

If light-water is used, that would simplify some of that journey. Long-standing fuel forms, known thermal hydraulics and proven-out safety cases minimize unknowns, while fresh ideas are transferred to tense-and-release packaging and logistics. And independent voices — from national labs to the World Nuclear Association — have said again and again that regulatory credibility and supply-chain realism matter as much as raw engineering.

What the funding enables for pilot and scale-up plans

The new capital fully finances the company’s 5 MW demonstration and pushes to tooling for a 20 MW commercial unit, the firm said. Look for investments in heavy-plate fabrication, thermal-hydraulic test loops, digital controls and site readiness as well as early manufacturing partnerships. The objective is not merely to switch on a first reactor, but to demonstrate that they have developed a playbook that can be used again and again at dozens of sites.

Outlook for Last Energy’s sealed-steel microreactor path

If Last Energy can validate performance, maintain construction schedules and navigate licensing, its sealed-steel microreactor could fill a niche to deliver firm power relatively quickly to isolated single campuses that cannot wait for new transmission. The funding is a significant vote of confidence, but the true test will come with execution at scale — where nuclear’s reliability meets factory cadence and learning-curve economics.